In chemistry, computational models may be getting worse

Ars Technica » Scientific Method 2017-01-11

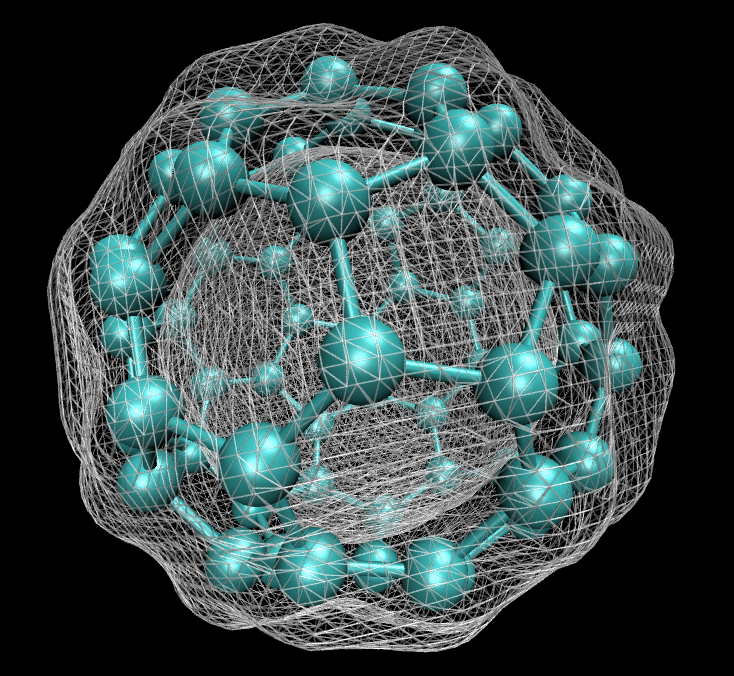

Enlarge / The electrons density of a buckminster fullerene molecule, calculated using density functional theory. (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Scientific research teams often use a computational model to understand their system better. In many fields, building these computational models is a full-time job, one that provides people with long careers. These models can require a sophisticated understanding of physics, chemistry, and biology, and they often require careful and informed tradeoffs between accuracy and computational speed.

This is especially true in chemistry, where the electrons that make everything work are governed by the quantum mechanical wave function. Computing for anything but the simplest atoms is impossible, yet we often want to understand what electrons are up to in complex bulk materials.

Over the last few decades, researchers have built a variety of algorithms meant to produce an approximate result, typically based on concepts collectively termed "density functional theory." But researchers have now shown that the most recent generations of algorithms have gotten extremely biased; they continue to get better at estimating the energy of the electrons, but they may be getting worse at getting their geometry right. Ironically, the problem may be an increased reliance on empirical data for developing the software.