Neanderthal teeth reveal lead exposure and difficult winters

Ars Technica » Scientific Method 2018-10-31

A new study of oxygen isotope ratios and heavy metals in the tooth enamel of Neanderthals who lived and died 250,000 years ago in southeast France suggests that they endured colder winters and more pronounced differences between seasons than the region’s modern residents. The two Neanderthals in the study also experienced lead exposure during their early years, making them the earliest known instances of this exposure.

Enduring harsh winters

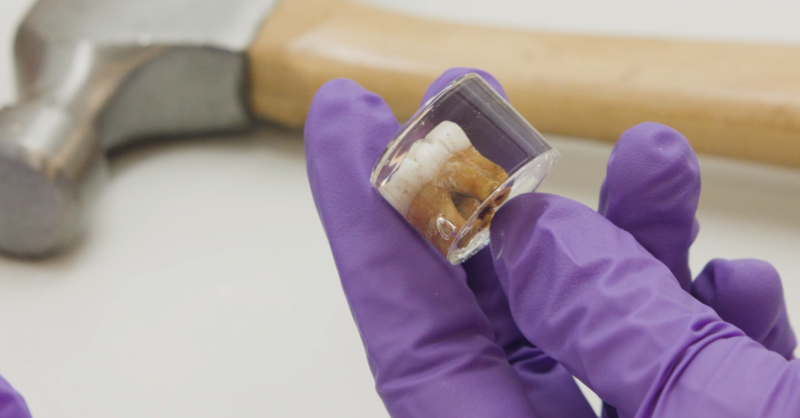

Tooth enamel forms in thin layers, and those layers record the chemical traces of a person’s early life—from climate to nutrition to chemical exposures—a little like tree rings on a much smaller scale. Archaeologist Tanya Smith of Griffith University and her colleagues examined microscopic samples of tooth enamel from two Neanderthal children from the Payre site in southeastern France. The teeth were radiocarbon dated to around 250,000 years ago, and the set of samples recorded about three years of life.

One important clue to past environments is oxygen, which comes from the water a person drank or the plants they ate. The ratio of the oxygen-18 isotope to oxygen-16 depends on temperature, precipitation, and evaporation. Generally, higher ratios of oxygen-18 indicate warmer, drier conditions with more evaporation.