Thoughts on the first half of Piketty’s Capital | Bryan Alexander

abernard102@gmail.com 2014-04-27

I’m halfway through Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century. It was some major implications for the future, including the future of education.

I’m halfway through Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century. It was some major implications for the future, including the future of education.

In this post I’d like to share some impressions of the book upon reaching its halfway point. I don’t want to summarize it (Doug Henwood does the best job I’ve seen), but address some key elements of content and style.

Piketty’s style is fascinating, and helps enliven what could otherwise be a dry study of statistics. He writes with humor, mocking his own profession:

[E]conomists like simple stories, even when they are only approximately correct (218)

[T]he discipline of economics has yet to get over its childish passion for mathematics and for purely theoretical and often highly ideological speculation (32)

…particularly when one belongs to the upper centiles of the [wealth] distribution and tends to forget it, as is often the case with economists (267)

The prose is occasionally elegant, even poetic:

Capital is never quiet: it is always risk-oriented and entrepreneurial, at least at its inception, yet it is always tends to transform itself into rents as it accumulates in large enough amounts – that is its vocation, its logical destination (115-6)

At times the book is mordant: “The top 10% [of a future America] could therefore use a small portion of their incomes to hire many of the bottom 50% as domestic servants” (257)

Key terms resonate, like patrimonial capitalism (173) or society of rentiers (264). George Lakoff should be impressed. Capital is also meticulously organized, offering frequent organizational statements to locate the reader within its argument and materials. Its introduction neatly lays out the book’s argument.

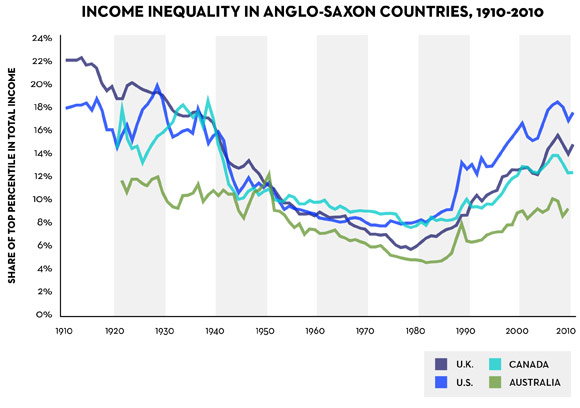

The key image of the book is a U-shaped curve (23). It occurs through chart after chart, showing different aspects of the same story: economic inequality being high before WWI, dropping for the middle of the 20th century, then rising up after 1980. That curve is a kind of multimedia aid, helping readers through mountains of data. For example:

Re: data, Piketty stashes much of the book’s research online. That’s a very useful way to combine digital with analog scholarship. We should expect more of this in academic publishing.

There’s an interesting politics to the book so far. Piketty clearly finds gross inequality abhorrent, and wants to address it. Its first words are a quote from the 1789 French revolutionary Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. The first chapter starts with an account of an armed battle between miners and management (39). And yet Piketty constantly distances himself from leftist thought and, with respect, Marx (8, 10) (“Marxist economists liked to show that capital’s share was always increasing… even if believing this sometimes required twisting the data” (219)) (“I was vaccinated for life against the conventional but lazy rhetoric of anticapitalism… much of which turned its back on the intellectual means necessary to push beyond [Communism]“, 31). He smacks down the liberal Gini coefficient (243) (“it is impossible to summarize a multidimensional reality with a uni-dimensional index without unduly simplifying matters and mixing up things that should not be treated together”, 266) (“statistical indices such as the Gini coefficient give an abstract and sterile view of inequality”, 267). So far this isn’t simply a left, liberal, or Marxist book, as some have charged.

One aspect of Piketty’s politics that I can’t pin down is his stance towards technology. He sees tech as powerfully shaping capital’s powers (212-213), but also as deeply unpredictable. He dismisses those who see technology as democratic, arguing that new inventions can empower capital as easily as those lacking capital (233-4).

One piece of the book’s argument which hasn’t won much attention is its emphasis on demographics. For all of Piketty’s emphasis on two formulas about economic distribution, changes in the number of people in a nation matter deeply. “[A] stagnant or, worse, decreasing population increases the influence of capital accumulated in previous generations” (84) Demographic growth keeps American inequality from soaring to even higher levels (154). “[T]he return to a historica regime of low growth, and in particular zero or even negative demographic growth, leads logically to the return of capital” (233; emphasis mine)

Predicting the future: Piketty hedges on this with every opportunity, despite the book’s putative ambitions. He qualifies his extrapolations, offering multiple options at each point.

[B]y 2100 the entire planet could look like Europe at the turn of the twentieth century, at least in terms of capital intensity. Obviously, this is just one possibility among others. (196)

The history of the past two centuries makes it highly unlikely that per capita output in the advanced countries will grow at a rate above 1.5% per year, but I am unable to predict whether the actual rate will be 0.5%, 1%, or 1.5% (95)

Who are the 1%? Piketty is clear that this is mostly C-suite executives, or “supermanagers”, especially in Britain and the United States. Athletic or cultural superstars barely count for 1/20th of that group, and financiers only 20%. (302-303)

So far, Capital is very convincing. His meticulous attention to data, steady re-examination of his own argument, and engagement with alternative models are, together, persuasive.

More notes to come after I finish the book’s second half. Education lies there as a topic, I think, along with explicit calls for policy actions.