Low turnout and polarization are a deadly combo for electoral stability

Ars Technica » Scientific Method 2020-01-25

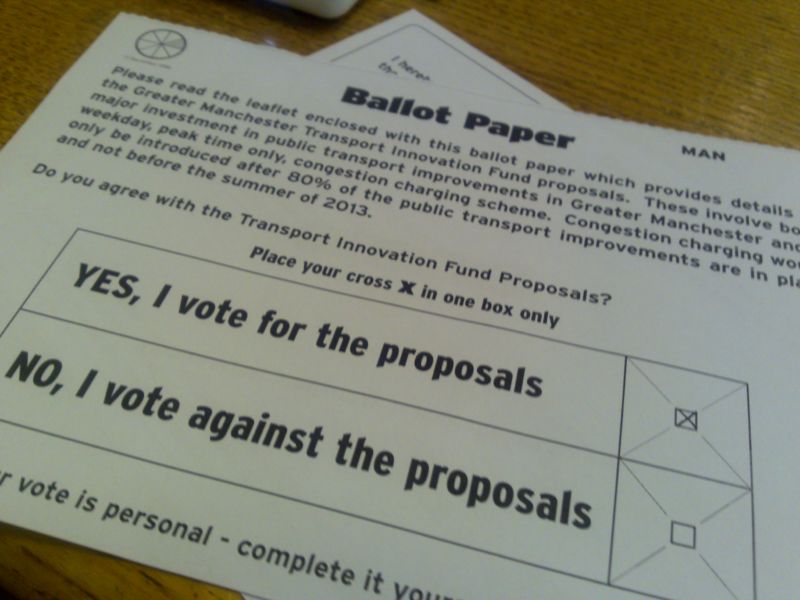

Enlarge (credit: Frankie Roberto / Flickr)

When people talk about elections like horse races, policy doesn't matter—all we care about is who's likely to win. In this fetid theory of elections, governments tend to represent a kind of dissatisfying average of voter opinion. Everyone gets a little bit of the stuff they want, and everyone gets a large dose of the stuff they don't want.

Given this model, is it possible for voter opinion to become, essentially, decoupled from election outcomes? Something like this might be the case, according to an overly general model produced by—you guessed it—physicists.

Elections are unfriendly things to model. Put yourself in the position of the party apparatchik. In an ideal world, you would come up with policy that you think would improve the nation and then present that to the electorate. That is a losing strategy. Instead, policies and candidates are selected based on the opinion of the electorate, which doesn't always know what will improve the nation. That creates a tightly coupled dynamic: the candidates offered are based on the opinion of the electorate, and they, in turn, influence the opinion of the electorate.