The feel-good open science story versus the preregistration (who do you think wins?)

peter.suber's bookmarks 2024-03-27

This is Jessica. Null results are hard to take. This may seem especially true when you preregistered your analysis, since technically you’re on the hook to own up to your bad expectations or study design! How embarrassing. No wonder some authors can’t seem to give up hope that the original hypotheses were true, even as they admit that the analysis they preregistered didn’t produce the expected effects. Other authors take an alternative route, one that deviates more dramatically from the stated goals of preregistration: they bury aspects of that pesky original plan and instead proceed under the guise that they preregistered whatever post-hoc analyses allowed them to spin a good story. I’ve been seeing this a lot lately.

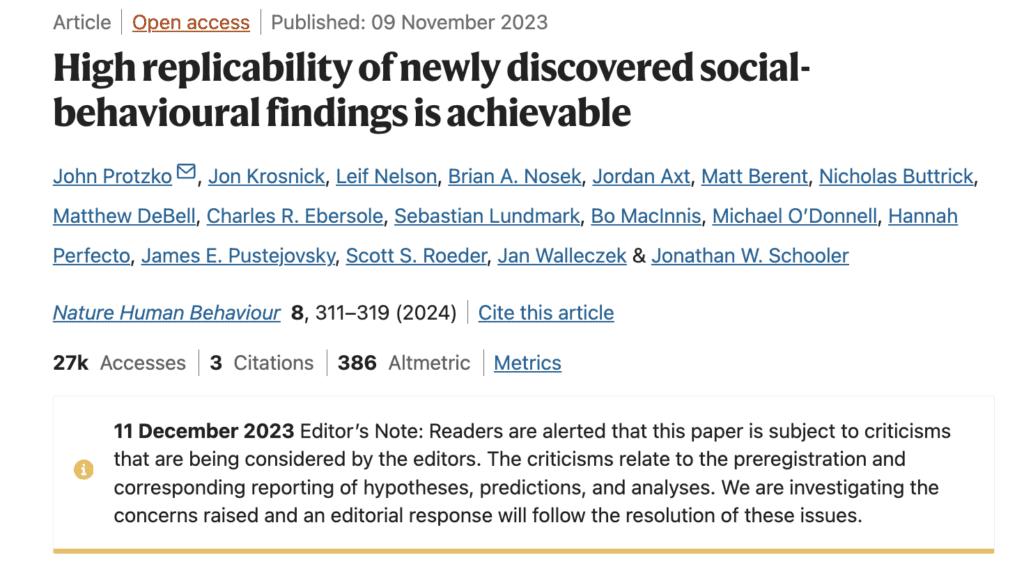

On that note, I want to follow up on the previous blog discussion on the 2023 Nature Human Behavior article “High replicability of newly discovered social-behavioural findings is achievable” by Protzko, Krosnick, Nelson (of Data Colada), Nosek (of OSF), Axt, Berent, Buttrick, DeBell, Ebersole, Lundmark, MacInnis, O’Donnell, Perfecto, Pustejovsky, Roeder, Walleczek, and Schooler. It’s been about four months since Bak-Coleman and Devezer posted a critique that raised a number of questions about the validity of the claims the paper makes.

This was a study that asked four labs to identify (through pilot studies) four effects for possible replication. The same lab then did a larger (n=1500) preregistered confirmation study for each of their four effects, documenting their process and sharing it with three other labs, who attempted to replicate it. The originating lab also attempted a self-replication for each effect.

The paper presents analyses of the estimated effects and replicability across these studies as evidence that four rigor-enhancing practices used in the post-pilot studies–confirmatory tests, large sample sizes, preregistration, and methodological transparency–lead to high replicability of social psychology findings. The observed replicability is said to be higher than expected based on observed effect sizes and power estimates, and notably higher than prior estimates of replicability in the psych literature. All tests and analyses are described as preregistered, and, according to the abstract, the high replication rate they observe “justifies confidence of rigour-enhancing methods to increase the replicability of new discoveries.”

On the surface it appears to be an all-around win for open science. The paper has already been cited over fifty times. From a quick glance, many of these citing papers refer to it as if it provides evidence of a causal effect that open practices lead to high replicability.

But one of the questions raised by Bak-Coleman and Devezer about the published version was about their claim that all of the confirmatory analyses they present were preregistered. There was no such preregistration in sight if you checked the provided OSF link. I remarked back in November that even in the best case scenario where the missing preregistration was found, it was still depressing and ironic that a paper whose message is about the value of preregistration could make claims about its own preregistration that it couldn’t back up at publication time.

Around that time, Nosek said on social media that the authors were looking for the preregistration for the main results. Shortly after Nature Human Behavior added a warning label indicating an investigation of the work:

And if I’m trying to tell the truth, it’s all bad

It’s been some months, and the published version hasn’t changed (beyond the added warning), nor do the authors appear to have made any subsequent attempts to respond to the critiques. Given the “open science works” message of the paper, the high profile author list, and the positive attention it’s received, it’s worth discussing here in slightly more detail how some of these claims seem to have come about.

The original linked project repository has been updated with historical files since the Bak-Coleman and Devezer critique. By clicking through the various versions of the analysis plan, analysis scripts, and versions of the manuscript, we can basically watch the narrative about the work (and what was preregistered) change over time.

The first analysis plan is dated October 2018 by OSF, and outlines a set of analyses of a decline effect, where effects decrease after an initial study, that differ substantially from the story presented in the published paper. This document first describes a data collection process for each of the confirmation studies and replications in two halves that splits the collection of observations into two parts, with 750 observations collected first, and the other 750 second. Each confirmation study and replication study are also assigned to either a) analyze the first half-sample and then the second half-sample or b) analyze the second half-sample and then the first half-sample.

There were three planned tests:

- Whether the effects statistically significantly increase or decrease depending on whether the effects belonged to the first or the second 750 half samples;

- Whether the effect sizes of the originating lab’s self-replication study is statistically larger or smaller than the originating lab’s confirmation study.

- Whether effects statistically significantly decrease or increase across all four waves of data collection (all 16 studies with all 5 confirmations and replications).

If you haven’t already guessed it, the goal of all this is to evaluate whether a supernatural-like effect resulted in a decreased effect size in whatever wave was analyzed second. It appears all this is motivated by hypotheses that some of the authors (okay, maybe just Schooler) felt were within the realm of possibility. There is no mention of comparing replicability in the original analysis plan nor the the preregistered analysis code uploaded last December in a dump of historical files by James Pustejovsky, who appears to have played the role of a consulting statistician. This is despite the blanket claim that all analyses in the main text were preregistered and further description of these analyses in the paper’s supplement as confirmatory.

The original intent did not go unnoticed by one of the reviewers (Tal Yarkoni) for Nature Human Behavior, who remarks:

The only hint I can find as to what’s going on here comes from the following sentence in the supplementary methods: “If observer effects cause the decline effect, then whichever 750 was analyzed first should yield larger effect sizes than the 750 that was analyzed second”. This would seem to imply that the actual motivation for the blinding was to test for some apparently supernatural effect of human observation on the results of their analyses. On its face, this would seem to constitute a blatant violation of the laws of physics, so I am honestly not sure what more to say about this.

It’s also clear that the results were analyzed in 2019. The first public presentation of results from the individual confirmation studies and replications can be traced to a talk Schooler gave at the Metascience 2019 conference in September, where he presents the results as evidence of an incline effect. The definition of replicability he uses is not the one used in the paper.

Cause if you’re looking for the proof, it’s all there

There are lots of clues in the available files that suggest the main message about rigor-enhancing practices emerged as the decline effects analysis above failed to show the hypothesized effect. For example, there’s a comment on an early version of the manuscript (March 2020) where the multi-level meta-analysis model used to analyze heterogeneity across replications is suggested by James. This is suggested after data collection has been done and initial results analyzed, but the analysis is presented as confirmatory in the paper with p-values and discussion of significance. As further evidence that it wasn’t preplanned, in a historical file added more recently by James, it is described as exploratory. It shows up later in the main analysis code with some additional deviations, no longer designated as exploratory. By the next version of the manuscript, it has been labeled a confirmatory analysis, as it is in the final published version.

This is pretty clear evidence that the paper is not accurately portraying itself.

Similarly, various definitions of replicability show up in earlier versions of the manuscript: the rate at which the replication is significant, the rate at which the replication effect size falls within the confirmatory study CI, and the rate at which replications produce significant results for significant confirmatory studies. Those which produce higher rates of replicability relative to statistical power are retained and those with lower rates are either moved to the supplement, dismissed, or not explored further because they produced low values. For example, defining replicability using overlapping confidence intervals was moved to the supplement and not discussed in the main text, with the earliest version of the manuscript (Deciphering the Decline Effect P6_JEP.docx) justifying its dismissal because it “produced the ‘worst’ replicability rates” and “performs poorly when original studies and replications are pre-registered.” Statistical power is also recalculated across revisions to align with the new narrative.

In a revision letter submitted prior to publication (Decline Effect Appeal Letterfinal.docx), the authors tell the reviewers they’re burying the supernatural motivation for study:

Reviewer 1’s fourth point raised a number of issues that were confusing in our description of the study and analyses, including the distinction between a confirmation study and a self-replication, the purpose and use of splitting samples of 1500 into two subsamples of 750, the blinding procedures, and the references to the decline effect. We revised the main text and SOM to address these concerns and improve clarity. The short answer to the purpose of many of these features was to design the study a priori to address exotic possibilities for the decline effect that are at the fringes of scientific discourse.

There’s more, like a file where they appeared to try a whole bunch of different models in 2020 after the earliest provided draft of the paper, got some varying results, and never disclose it in the published version or supplement (at least I didn’t see any mention). But I’ll stop there for now.

C’mon baby I’m gonna tell the truth and nothing but the truth

It seems clear that the dishonesty here was in service of telling a compelling story about something. I’ve seen things like this transpire plenty of times: the goal of getting published leads to attempts to find a good story in whatever results you got. Combined with the appearance of rigor and a good reputation, a researcher can be rewarded for work that on closer inspection involves so much post-hoc interpretation that the preregistration seems mostly irrelevant. It’s not surprising that the story here ends up being one that we would expect some of the authors to have faith in a priori.

Could it be that the authors were pressured by reviewers or editors to change their story? I see no evidence of that. In fact, the same reviewer who noted the disparity between the original analysis plan and the published results encouraged the authors to tell the real story:

I won’t go so far as to say that there can be no utility whatsoever in subjecting such a hypothesis to scientific test, but at the very least if this is indeed what the authors are doing, I think they should be clear about that in the main text, otherwise readers are likely to misunderstand what the blinding manipulation is supposed to accomplish, and are at risk of drawing incorrect conclusions

You can’t handle the truth, you can’t handle it

It’s funny to me how little attention the warning label or the multiple points raised by Bak-Coleman and Devezer (which I’m simply concretizing here) have drawn, given the zeal with which some members of open science crowd strike to expose questionable practices in other work. My guess is this is because of the feel-good message of the paper and the reputation of the authors. The lack of attention seems selective, which is part of why I’m bringing up some details here. It bugs me (though doesn’t not surprise me) to think that whether questionable practices get called out depends on who exactly is in the author list.

What do I care? Why should you?

On some level, the findings the paper presents – that if you use large studies and attempt to eliminate QRPs, you can get a high rate of statistical significance – are very unsurprising. So why care if the analyses weren’t exactly decided in advance? Can’t we just call it sloppy labeling and move on?

I care because if deception is occurring openly in papers published in a respected journal for behavioral research by authors who are perceived as champions of rigor, then we still have a very long way to go. Interpreting this paper as a win for open science, as if it cleanly estimated the causal effect of rigor-enhancing practices is not, in my view, a win for open science. The authors’ lack of concern for labeling exploratory analysis as confirmatory, their attempt to spin the null findings from the intended study into a result about effects on replicability even though the definition they use is unconventional and appears to have been chosen because it led to a higher value, and the seemingly selective summary of prior replication rates from the literature should be acknowledged as the paper accumulates citations. At this point months have passed and there have not been any amendments to the paper, nor admission by the authors that the published manuscript makes false claims about the preregistration status. Why not just own up to it?

It’s frustrating because my own methodological stance has been positively impacted by some of these authors. I value what the authors call rigor-enhancing practices. In our experimental work, my students and I routinely use preregistration, we do design calculations via simulations to choose sample sizes, we attempt to be transparent about how we arrive at conclusions. I want to believe that these practices do work, and that the open science movement is dedicated to honesty and transparency. But if papers like the Nature Human Behavior article are what people have in mind when they laud open science researchers for their attempts to rigorously evaluate their proposals, then we have problems.

There are many lessons to be drawn here. When someone says all the analyses are preregistered, don’t just accept them at their word, regardless of their reputation. Another lesson that I think Andrew previously highlighted is that researchers sometimes form alliances with others that may have different views for the sake of impact but this can lead to compromised standards. Big collaborative papers where you can’t be sure what your co-authors are up to should make all of us nervous. Dishonestly is not worth the citations.

Writing inspiration from J.I.D. and Mereba.