To make Curiosity (et al) more curious, NASA and ESA smarten up AI in space

Ars Technica » Scientific Method 2018-07-16

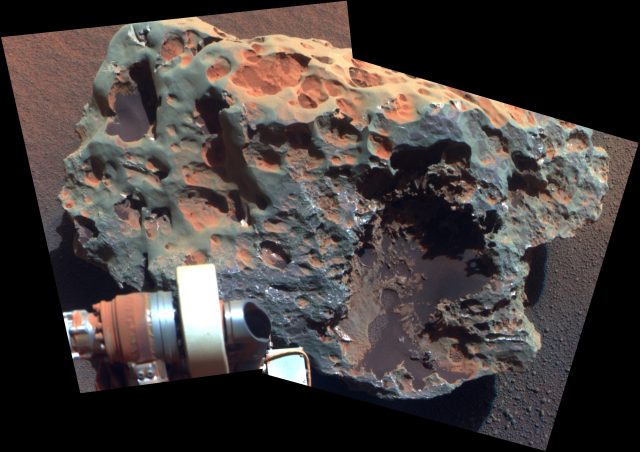

Block Island, the largest meteorite yet found on Mars and one of several identified by the Mars Exploration Rovers. (credit: NASA)

NASA's Opportunity Mars rover has done many great things in its decade-plus of service—but initially, it rolled 600 feet past one of the initiative’s biggest discoveries: the Block Island meteorite. Measuring about 67 centimeters across, the meteorite was a telltale sign that Mars' atmosphere had once been much thicker, thick enough to slow down the rock flying at a staggering 2km/s so that it did not disintegrate on impact. A thicker atmosphere could mean a more gentle climate, possibly capable of supporting liquid water on the surface, maybe even life.

Yet, we only know about the Block Island meteorite because someone on the Opportunity science team manually spotted an unusual shape in low-resolution thumbnails of the images and decided it was worth backtracking for several days to examine it further. Instead of this machine purposefully heading toward the rock right from the get-go, the team barely saw perhaps its biggest triumph in the rear view mirror. "It was almost a miss," says Mark Woods, head of autonomy and robotics at SciSys, a company specializing in IT solutions for space exploration that works for the European Space Agency (ESA), among others.

Opportunity, of course, made this near-miss maneuver all the way back in July 2009. If NASA were to attempt a similar initiative in a far-flung corner of the galaxy today—as the space organization plans to in 2020 with the Mars 2020 rover (the ESA has similar ambitions with its ExoMars rover that year)—modern scientists have one particularly noteworthy advantage that has developed since.