Forecasting El Niño with entropy—a year in advance

Ars Technica » Scientific Method 2019-12-28

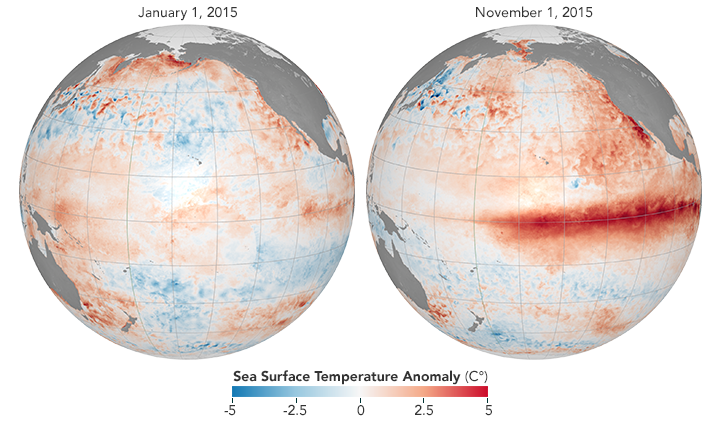

Enlarge / A strong El Niño developed in 2015, visible here from temperature departures from average. (credit: NASA EO)

We generally think of weather as something that changes by the day, or the week at the most. But there are also slower patterns that exist in the background, nudging your daily weather in one direction or another. One of the most consequential is the El Niño Southern Oscillation—a pattern of sea surface temperatures along the equatorial Pacific that affects temperature and precipitation averages in many places around the world.

In the El Niño phase of this oscillation, warm water from the western side of the Pacific leaks eastward toward South America, creating a broad belt of warm water at the surface. The opposite phase, known as La Niña, sees strong trade winds blow that warm water back to the west, pulling up cold water from the deeps along South America. The Pacific randomly wobbles between these phases from one year to the next, peaking late in the calendar.

Since this oscillation has such a meaningful impact on weather patterns—from heavy precipitation in California to drought in Australia—forecasting the wobble can provide useful seasonal outlooks. And because it changes fairly slowly, current forecasts are actually quite good out to about six months. It would be nice to extend that out further, but scientists have repeatedly run into what they've termed a “spring predictability barrier.” Until they see how the spring season plays out, the models have a hard time forecasting the rest of the year.