First room-temperature superconductor reported

Ars Technica » Scientific Method 2020-10-14

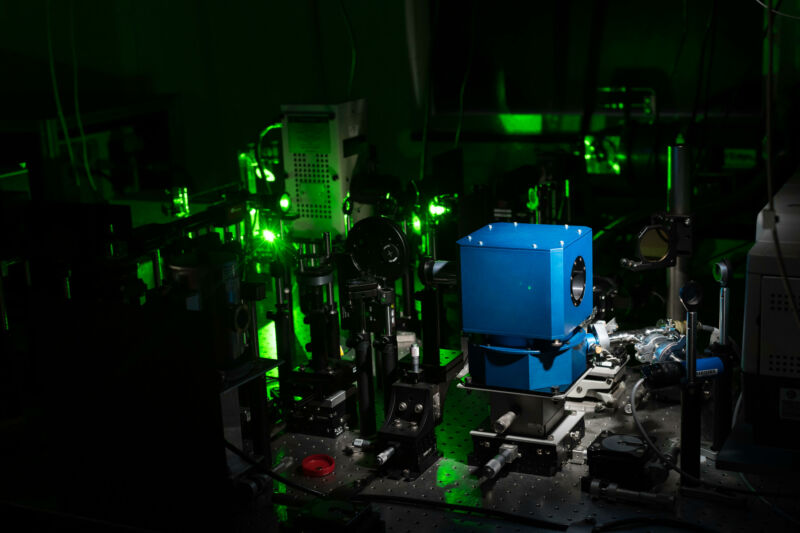

Enlarge / Equipment including a diamond anvil cell (blue box) and laser arrays in the lab of Ranga Dias at the University of Rochester. Undoubtedly, they cleaned up the typical mess of cables and optical hardware before taking the photo.

In the period after the discovery of high-temperature superconductors, there wasn't a good conceptual understanding of why those compounds worked. While there was a burst of progress toward higher temperatures, it quickly ground to a halt, largely because it was fueled by trial and error. Recent years brought a better understanding of the mechanisms that enable superconductivity, and we're seeing a second burst of rapidly rising temperatures.

The key to the progress has been a new focus on hydrogen-rich compounds, built on the knowledge that hydrogen's vibrations within a solid help encourage the formation of superconducting electron pairs. By using ultra-high pressures, researchers have been able to force hydrogen into solids that turned out to superconduct at temperatures that could be reached without resorting to liquid nitrogen.

Now, researchers have cleared a major psychological barrier by demonstrating the first chemical that superconducts at room temperature. There are just two catches: we're not entirely sure what the chemical is, and it only works at 2.5 million atmospheres of pressure.