Mouse embryos grow for days in culture, but the requirements are a bit nuts

Ars Technica » Scientific Method 2021-03-20

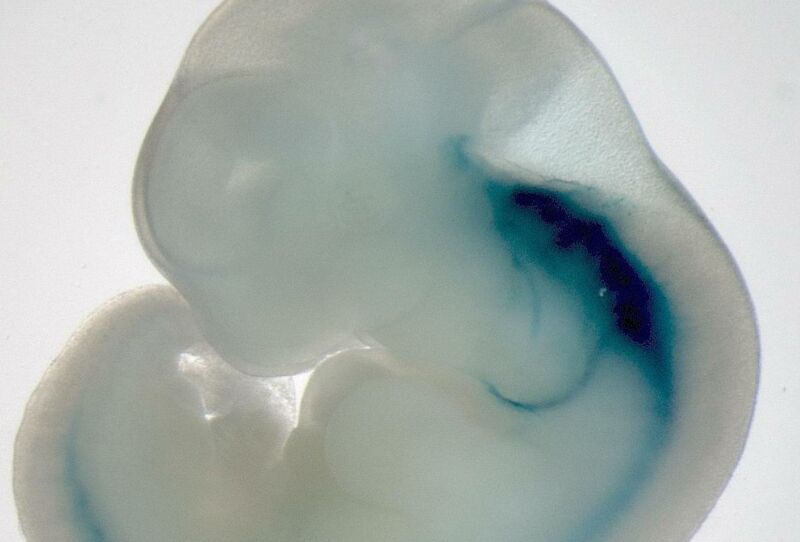

Enlarge / A mouse embryo with the nervous system highlighted in blue. (credit: Lawrence Berkeley Lab)

Embryos start out as a single cell, and have to go from there to a complicated array of multiple tissues. For organisms like insects or frogs, that process is pretty easy to study, since development takes place in an egg that's deposited into the environment shortly after fertilization. But for mammals, where all of development takes place inside the reproductive tract, understanding the earliest stages of development is a serious challenge. Performing any experiments on a developing embryo is extremely difficult, and effectively impossible at some stages.

This week, however, progress has been made with both human and mouse embryos. On the human side, researchers have used induced stem cells to create embryo-like bodies that perform the first key step in development, catching them up to where mouse research has been for decades. On the mouse side, however, a research team has gotten mouse embryos to go for nearly a week outside the uterus. While that opens up a world of experiments that hadn't previously been possible, the requirements for getting it to work means that it's unlikely to be widely adopted.

To grow mice, you need rats

The mouse work was somewhat more interesting technically, so we'll get to that first. One of the most critical steps in the development of vertebrates is called gastrulation. The process takes some cells that have been set aside during the early embryo, and converts them into three critical layers that go on to form the embryo: the skin and nerves, the lining of the gut, and everything else.