Codices of Tetepilco

Language Log 2024-03-27

From Tlacuilolli*, the blog about Mesoamerican writing systems, by Alonso Zamora, on March 21, 2024:

*At the top left of the home page of this blog, there is a tiny seated figure (click to embiggen) with a sharp instrument held vertically in his right hand carving a glyph on a square block held in his left hand. Emitting from his mouth is a blue, cloud-like puff. Does that signify recognition the basis of what he is writing is speech?

"New Aztec Codices Discovered: The Codices of San Andrés Tetepilco"

They are beautiful:

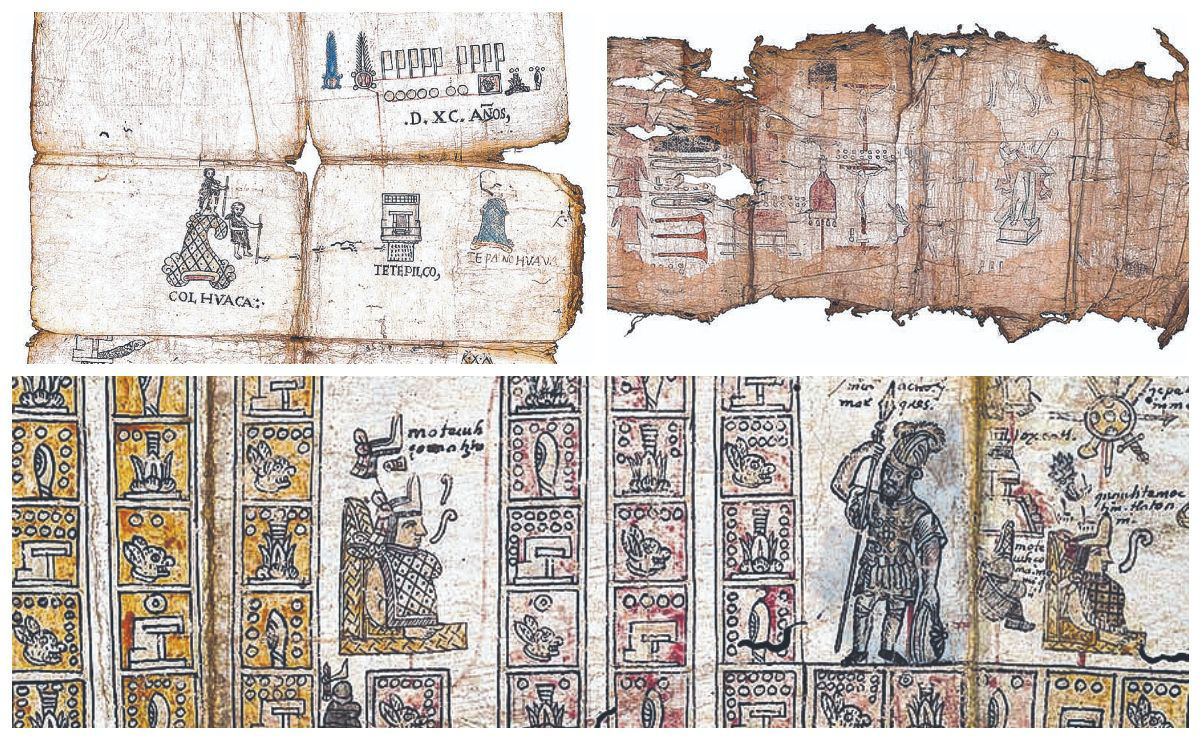

Figure 1. Codices of San Andrés Tetepilco: a) Map of the Founding of San Andrés Tetepilco; b) Inventory of the Church of San Andrés Tetepilco; c) Tira of San Andrés Tetepilco

Figure 1. Codices of San Andrés Tetepilco: a) Map of the Founding of San Andrés Tetepilco; b) Inventory of the Church of San Andrés Tetepilco; c) Tira of San Andrés Tetepilco

The newly discovered corpus was acquired by the Mexican government from a local family that wants to remain anonymous, but which were not collectors but rather traditional stewards of the cultural legacy of Culhuacan and Iztapalapa, and it is now stored at the library of the National Institute of Anthropology and History of Mexico. It comprises three codices. The first is called Map of the Founding of Tetepilco, and is a pictographic map which contains information regarding the foundation of San Andrés Tetepilco, as well as lists of toponyms to be found within Culhuacan, Tetepilco, Tepanohuayan, Cohuatlinchan, Xaltocan and Azcapotzalco. The second, the Inventory of the Church of San Andrés Tetepilco, is unique, as [philologist Michel] Oudijk remarks, since it is a pictographic inventory of the church of San Andrés Tetepilco, comprising two pages. Sadly, it is very damaged.

Finally, the third document, now baptised as the Tira of San Andrés Tetepilco, is a pictographic history in the vein of the Boturini and the Aubin codices, comprising historical information regarding the Tenochtitlan polity from its foundation to the year 1603. It seems to belong to the same family as the Boturini, the Aubin, the Ms. 40 and the Ms. 85 of Paris, that is to say, some of the main codices dealing with Aztec imperial history, and Brito considers it as a sort of bridge between the Boturini and the Aubin, since its pictographic style is considerably close to the early colonial one of the former, rather than the late colonial one of the latter. It comprises 20 rectangular pages of amate paper, and contains new and striking iconography, including a spectacular depiction of Hernán Cortés as a Roman soldier. In the Aztec side of things, new iconography of Moctezuma Ilhuicamina during his conquest of Tetepilco is presented (Figure 1).

Of course, new and very interesting examples of Aztec writing are contained throughout all these documents, including old and new toponyms, spellings of Western and Aztec names, and even some information that confirms that some glyphs formerly considered as hapax, as the chi syllabogram in the spelling of the name Motelchiuhtzin in Codex Telleriano-Remensis 43r, discussed in another post of this blog, were not anomalous but possibly conventional. Besides logosyllabic spellings, the presence of pictographs with alphabetic glosses in Nahuatl will be of great help to ascertain the functioning of this still controversial part of the Aztec communication system.

The last sentence quoted above will be of particular interest to historians of writing. I myself look forward to future communications on this topic.

Selected readings

- "Was rongorongo an independent invention of writing?" (3/21/24)

- "Polynesian sweet potatoes and jungle chickens: verbal vectors" (1/18/23)

[Thanks to Hiroshi Kumamoto]