Hendiadys and sleeping in parks

Language Log 2024-04-22

Samuel Bray, "Cruel AND Unusual?", Reason 4/21/2024:

On Monday, the Supreme Court will hear argument in an Eighth Amendment case, City of Grants Pass, Oregon v. Johnson. One thing I will be watching for is whether the justices in their questions treat "cruel and unusual" as two separate requirements, or as one.

The Eighth Amendment (to the U.S. Consitution) says that "Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted."

And the issue in the cited Supreme Court case is "Whether the enforcement of generally applicable laws regulating camping on public property constitutes “cruel and unusual punishment” prohibited by the Eighth Amendment." (More here, here, and elsewhere…)

Samuel Bray's interest in the interpretation of "cruel and unusual" follows up on his 2016 Virginia Law Review article, "'Necessary and Proper' and 'Cruel and Unusual': Hendiadys in the Constitution", Va. L. Rev. (2016):

This Article attempts to shed new light on the original meaning of the Necessary and Proper Clause, and also on another Clause of the U.S. Constitution, the Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause. The phrases “necessary and proper” and “cruel and unusual” can be read as instances of an old but now largely forgotten figure of speech. That figure is hendiadys, in which two terms separated by a conjunction work together as a single complex expression.

A bit more of that article's argument:

First consider “cruel and unusual.” These are often understood as two separate requirements: punishments are prohibited only if they are cruel and unusual. Yet this phrase can easily be read as a hendiadys in which the second term in effect modifies the first: “cruel and unusual” would mean “unusually cruel.” When this reading is combined with the work of Professor John Stinneford, which shows that “unusual” was used at the Founding as a term of art for “contrary to long usage,” it suggests that the Clause prohibits punishments that are innovatively cruel. In other words, the Clause is not a prohibition on punishments that merely happen to be both cruel and innovative. It is a prohibition on punishments that are innovative in their cruelty.

You can read the rest for yourself…

The Wikipedia page explains that the origin of the word hendiadys is the Greek phrase ἓν διὰ δυοῖν "one through two".

One of the OED's earliest citations is to Angell Day's 1592 English Secretorie (revised edition) — the first edition was printed in 1586, which would make it the earliest citation.

Project Gutenberg has a transcription of the 1599 edition, in which the relevant definition reads

Hendiadis, when one thing of it selfe intire, is diuersly layde open, as to saie, On iron and bit he champt, for on the iron bitte hee champt: And part and pray we got, for part of the pray: Also by surge and sea we past, for by surging sea we past. This also is rather Poeticall then other wise in vse.

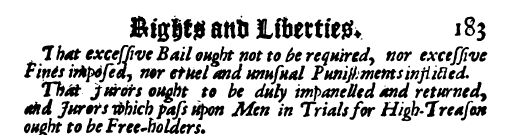

I'm not familiar with the literature on the wording of the Bill of Rights, so maybe this is common knowledge — but a quick Google Books search reveals that the section on "Rights and Liberties" in this 1696 book lists a 1688 act of Parliament that contains (along with many other principles) almost exactly the wording of the Eighth Amendment:

Whereas the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons assembled at Westminster, lawfully, fully and freely representing all the Estates of the People of this Realm, did upon the 13th day of February in the year of our Lord One thousand six hundred eighty eight, present unto their Majesties, then called and known by the Names and Stile of William and Mary, Prince and Princess of Orange, being present in their proper Persons, a certain Declaration in Writing, made by the said Lords and Commons in the Words following, viz.

[… lots of stuff omitted …]

That excessive Bail ought not to be required, nor excessive Fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual Punishments inflicted.