The shape of a spoken phrase in Mandarin

Language Log 2014-06-21

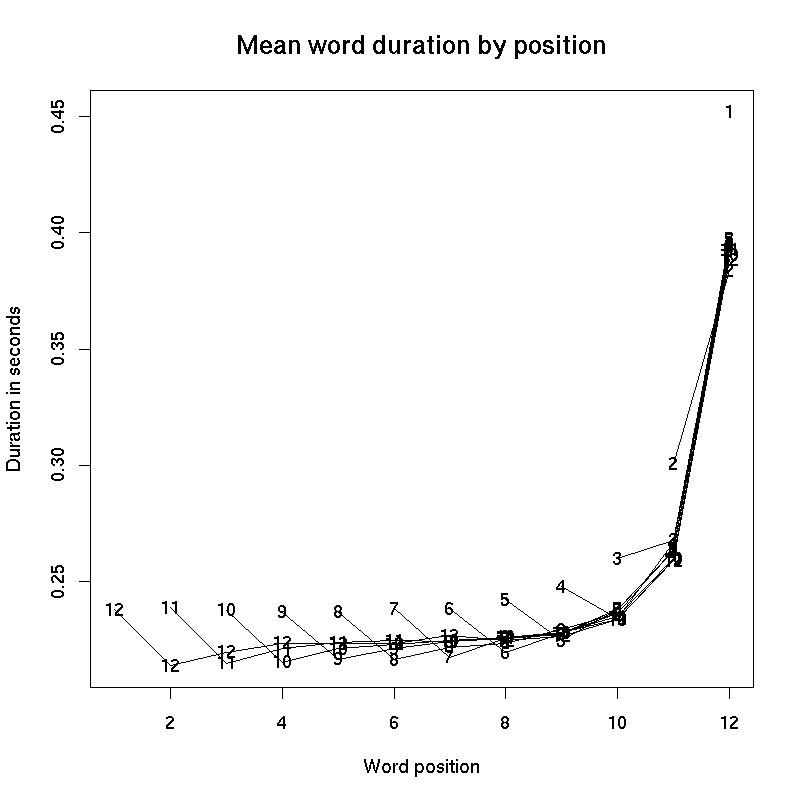

A few years ago, with Jiahong Yuan and Chris Cieri, I took a look at variation in English word duration by phrasal position, using data from the Switchboard conversational-speech corpus ("The shape of a spoken phrase", LLOG 4/12/2006; Jiahong Yuan, Mark Liberman, and Chris Cieri, "Towards an Integrated Understanding of Speaking Rate in Conversation", InterSpeech 2006). As is often the case for simple-minded analysis of large speech datasets, this exercise showed a remarkably consistent pattern of variation — the plot below shows mean duration by position for phrases from 1 to 12 words long:

The Mandarin Broadcast News collection discussed in a recent post ("Consonant effects on F0 in Chinese", 6/12/2014) lends itself to a similar analysis of phrase-position effects on speech timing. So for this morning's Breakfast Experiment™, I ran a couple of scripts to take a first look.

As described in Jiahong Yuan, Neville Ryant, and Mark Liberman, "Automatic Phonetic Segmentation in Mandarin Chinese: Boundary Models, Glottal Features and Tone", ICASSP 2014, we started with a 16-year-old published dataset (1997 Mandarin Broadcast News Speech LDC98S73, 1997 Mandarin Broadcast News Transcripts LDC98T24), and processed it as follows:

We extracted the “utterances” (the between-pause units that are time-stamped in the transcripts) from the corpus and listened to all utterances to exclude those with background noise and music. Utterances from speakers whose names were not tagged in the corpus or from speakers with accented speech were also excluded. The final dataset consisted of 7,849 utterances from 20 speakers. We randomly selected 300 utterances from six speakers (50 utterances for each speaker), three male and three female, to compose a test set. The remaining 7,549 utterances were used for training.

For this morning's exercise, I further divided the training-set utterances wherever there was a significant silent pause, yielding 10,699 breath-group-like phrases comprising 96,697 syllables. The resulting dataset is significantly larger than the laboratory collections used in typical phonetics experiments. But it's small compared to Switchboard – about 10,000 phrases vs. about 250,000 phrases, in the versions used to produce this post's plots; and Switchboard in turn is small by the standards of modern speech-technology research.

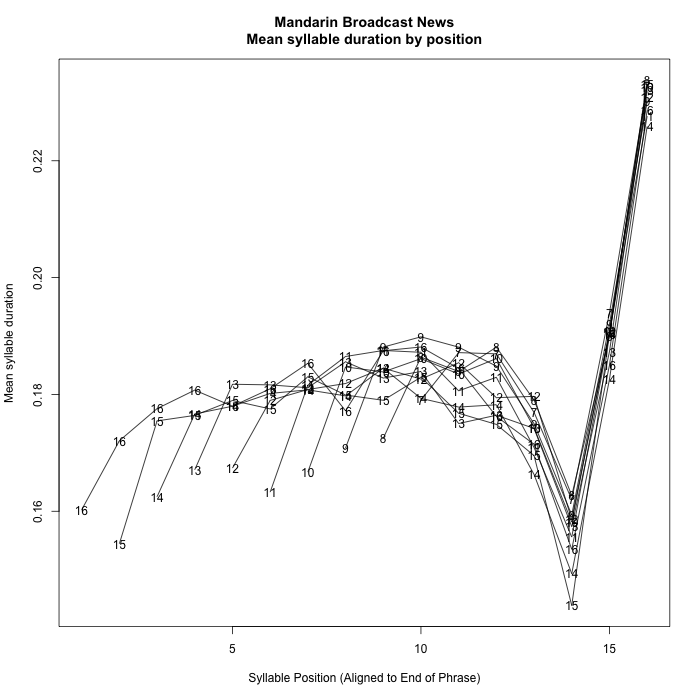

Still, a very consistent pattern of syllable duration by phrasal position emerges. This plot shows average duration by position for phrases between 7 and 16 syllables long:

The expected phrase-final lengthening emerges clearly, as it did in the case of English. But there are also some striking differences — here's are side-by-side plots for comparison:

English words (Switchboard)Mandarin syllables (Broadcast News)

The Mandarin data shows a striking shortening effect in the third syllable from the end of the phrase — and a smaller shortening effect in the fourth position. The Mandarin measurements also show shortening of the phrase-initial syllable, and a tendency for phrase-medial syllables (after the first few, and before the final four) to be longer.

These differences might be a language effect, that is, a difference between English and Mandarin phrasal speech timing. But they might also arise because we're looking at syllable durations rather than word durations, or because the speech is broadcast news reading rather than telephone conversations, or because of characteristic phrase-final syntactic or lexical patterns in Mandarin news broadcasts, or . . .

Despite this indeterminacy, the patterns are striking enough to be worth further investigation, I think. During some other breakfast period, I (or others) could look at syllable-wise patterns in Switchboard, or word-wise patterns in the Mandarin broadcast data. And with a bit of additional high-quality forced alignment, we can compare published English broadcast material, or Mandarin conversational material, or for that matter different sorts of speech in other languages — and use regression methods to try to untangle the causes and effects.

As I wrote a few years ago:

From the perspective of a linguist, today's vast archives of digital text and speech, along with new analysis techniques and inexpensive computation, look like a wonderful new scientific instrument, a modern equivalent of the 17th-century inven+on of the telescope and microscope.

We can now observe linguistic patterns in space, time, and cultural context, on a scale three to six orders of magnitude greater than in the past, and simultaneously in much greater detail than before.

When we focus our new instruments on a familiar object, we often see interesting and unexpected things — and that's exactly what happened here. Seeing such patterns is the starting-point of science, not the end. But generating and testing hypotheses in hours rather than months is still a big win.

In this case, the dataset is barely one or two decimal orders of magnitude larger than a typical laboratory phonetics experiment, but there are still enough exemplars at each phrase length to see the effect:

(In comparison, the Switchboard dataset had between 12,124 and 151,995 exemplars for each phrasal word-count.)

And since the speech was collected and transcribed 17 years ago for another purpose, and automatically segmented recently as part of yet another series of experiments, the additional time expended in data collection and measurement is reduced to zero, or at least to the few minutes needed to write a couple of analysis scripts.

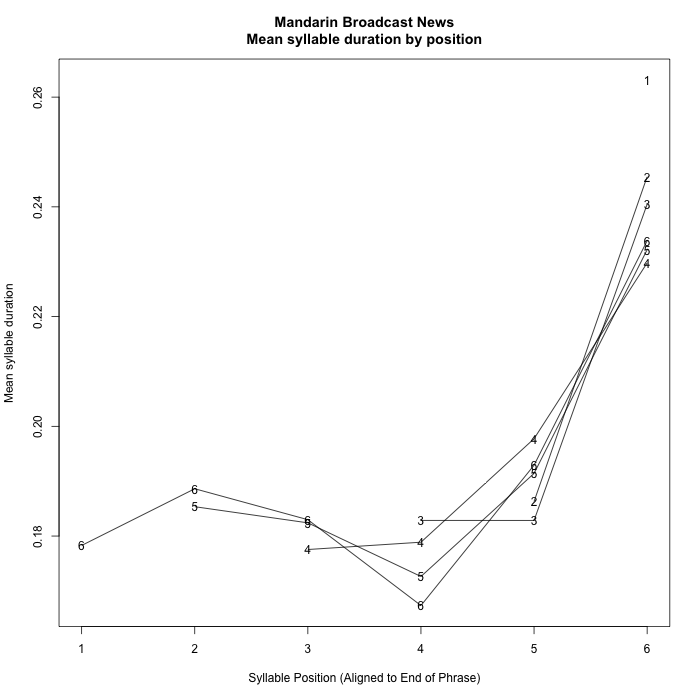

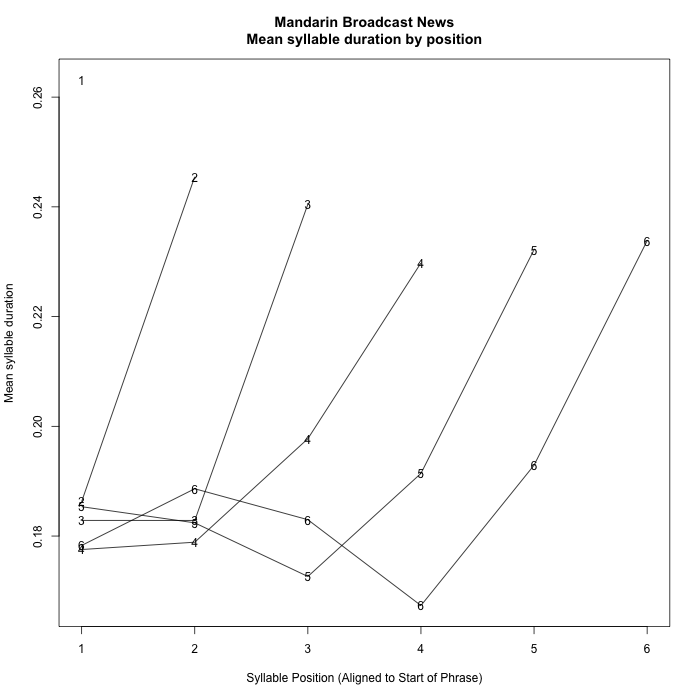

For completeness, here's the plot for phrase lengths from 1 to 6 syllables:

I left those out of the earlier plot because at those shorter phrase lengths, the phrase-final and phrase-initial effects are still apparently overlapping and interacting, so that the graphs are harder to read.

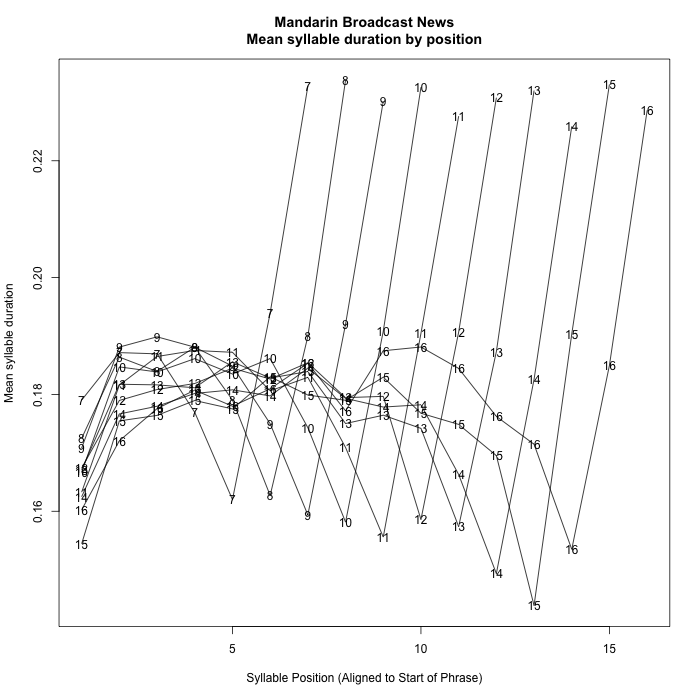

Here's the same data with the plots aligned from the start of the phrase rather than the end:

And the syllable-duration means by phrase length, in an R-accessible form, are here, so you can re-plot them in other ways if you prefer.