Steampunk phonetics

Language Log 2015-08-23

From the Transactions of the Philological Society, 1873-74, "VIII. — On the Physical Constituents of Accent and Emphasis: By Alexander J. Ellis, Esq., President":

Phonoautographic Sound-curves. Any disturbance in the air produces a series of alternate condensations and rarefactions, which, coming in contact with the drum of the ear, cause it to vibrate, in such a manner as to produce, after various internal modifications, the well-known sensation of sound. The most convenient way of analyzing this sensation is to analyze the motion of a single point in the drum of the ear. This is effected by an instrument called the phonautograph, consisting of a metal paraboloidal reflector (answering to the passage leading to the drum of the ear), truncated by a plane passing through its focus and perpendicular to its axis, over which opening is stretched a delicate membrane, ordinarily bladder (answering to the drum of the ear). At one point of this membrane is fixed a style (ordinarily a piece of quill), which rests against a cylinder, over which is rolled a piece of paper delicately coated with lampblack. A disturbance of the air inside the reflector causes the style to move backwards and forwards on the lampblacked surface, which it scrapes off. If the cylinder remain at rest, this produces a white straight line of moderate length. But if, as is usual, the cylinder be caused to revolve with a uniform motion, the style scratches out a white undulating line, which may be called a sound-curve, and which is the visible symbol of the invisible disturbance of the air.

I'll have more to say about this fascinating document, about Alexander J. Ellis (see also Jonathan P.J. Stock, "Alexander J. Ellis and his place in the history of ethnomusicology", Ethnomusicology 2007), and about Ellis's 1872 Philological Society Presidential Address ("On the Relation of Thought to Sound as the Pivot of Philological Research").

For now, I'll just add Ellis's list of "matters to be considered in a sound-curve", and his quaint account of sound-curve duration:

A sound-curve is generally made up of repeated undulations, and is considered to be unaltered so long as these undulations recur in precisely the same manner. There are four principal matters to be considered in a sound-curve, which will be here called length, pitch, force, and form, the nature of which I proceed to explain.

Means exist for accurately determining the length of the medial straight line, which would be described by a fixed, instead of a vibrating style, in one second of time, and would then pass from the beginning to the end of a sound-curve. The ratio of the length of such portion of this line as passes through an unaltering portion of the sound-curve, to the length corresponding to one second of time, gives the length of time during which the disturbance of air lasted unchanged, that is, the duration of the sound in seconds. This will hereafter be called its length.

I'll also note in passing that the term "Sound-curve" — what we would now call a "(sound) waveform" — did not die with Ellis, but was used as late as 1937 in Sir James Jean's Science and Music:

We have seen that all sound, whether pleasant or unpleasant, whether music or mere noise, is represented by a curve. We shall first examine the general properties of such a curve, trying to discover why some curves produce pleasure when they reach our ears and some pain. We must then consider the transmission of sound, discussing how best to retain the pleasurable qualities in our sound-curve, as it passes on from one carrier to another, and how far it is possible to prevent unpleasant qualities contaminating the curve. Finally we shall have to discuss the strange transformations that the sound-curve may undergo inside our heads.

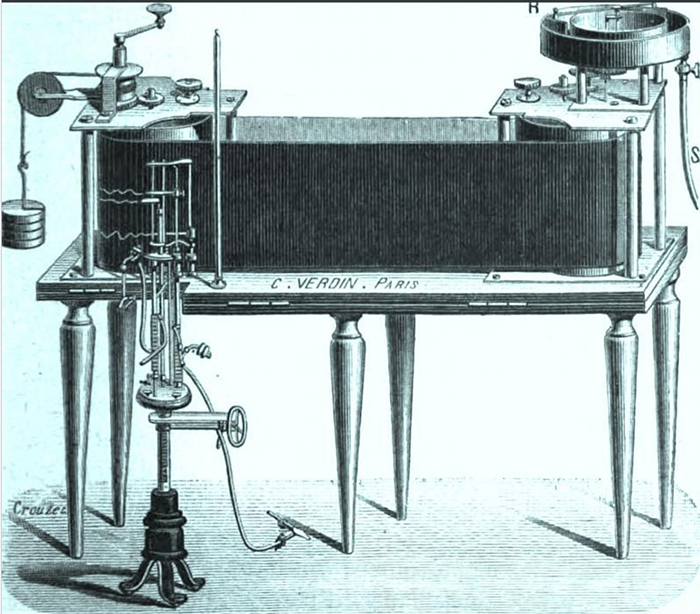

As background, this is what a "phonoautograph" device of Ellis's era looked like (source and discussion here):

And this is the sort of output it produced (source and discussion here):

A later (c. 1913) version of the same sort of device, from L'abbé Rousselot's lab at the Sorbonne, is illustrated in my post "Empirical Foundations of Linguistics", 7/26/2011. Rousselot's machine has a much longer piece of lampblacked recording material, a clockwork motor to drive the cylinder, and multiple inputs for things like nasal airflow:

(See also "God's own Englishman with a tube up his nose", 3/23/2007.)