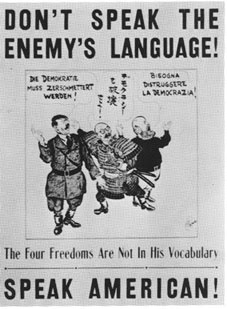

DON'T SPEAK THE ENEMY'S LANGUAGE!

Language Log 2016-02-23

This World War II American propaganda poster speaks for itself:

A poster of WWII era discouraging the use of Italian, German, and Japanese. (Source)

A poster of WWII era discouraging the use of Italian, German, and Japanese. (Source)

Our first task is to transcribe and translate the German, Japanese, and Italian:

Adolf Hitler:

Die Demokratie muss zerschmettert werden! ("Democracy must be destroyed!")

Tōjō Hideki:

Demokurashī o hakai seyo デモクラシーを破壊せよ。 ("Destroy democracy!")

Benito Mussolini (but I've never seen photographs of Mussolini with a beard, or is that supposed to be a scarf around his neck? — the cartoon is not very well drawn, and maybe what looks like a beard is just the shadow of the face):

Bisogna distruggere la democrazia! ("We must destroy democracy; democracy must be destroyed" [an impersonal construction — "it is necessary to"])

The above poster was called to my attention by Charlie Ruland, who sent in the following message:

I am an ethnic German follower of Language Log and have read your post, "What does "Schmetterling" sound like to a German?." However, I was unable to leave a comment there this morning; it seems that commenting has been closed.

Anyway, the other day I stumbled upon the Wikipedia article German language in the United States, and in the section Persecution during World War I I discovered a poster that shows Hitler saying "Die Demokratie muss zerschmettert werden!" ("Democracy must be destroyed!", literally "smashed"). The poster also shows Mussolini and Tōjō uttering the same sentence in their respective languages, and the English message is: "DON'T SPEAK THE ENEMY'S LANGUAGE! The Four Freedoms Are Not In His Vocabulary. SPEAK AMERICAN!" According to the poster's file description on Wikimedia Commons "[t]his sign was hung in post offices and in government buildings during World War II […] between circa 1941 and circa 1945".

I am not going to comment on interesting linguistic details such as the use of collective the enemy and his vocabulary or of American referring to (American) English here. My contribution to the topic of the Schmetterling meme is as follows:

I take this poster as evidence that the syllables schmetter were known to a great many Americans as an indication of German fascism as far back as the early 1940s, and have been ever since. Taking into account the US Supreme Court case Meyer v. Nebraska of 1923 such a poster in US post offices and government buildings may seem surprising (or rather: unconstitutional) but it doesn't seem the average American really cared or cares. I have met many Germans who were extremely well-informed about the history of linguistic rights in the US and elsewhere — much more so than almost all US citizens, it seems — and who felt that making fun of a linguistic minority is equivalent to making fun of, say, an ethnic, racial or sexual minority: calling a language ugly is not a far cry from calling it primitive and incapable of expressing certain notions that are "Not In His Vocabulary". (I even believe such an attitude contributed to weakening German resistance to fascism in WWII, and that this topic is also related to Frau Merkel's current policy of admitting hundreds of thousands of "orientals" to Germany, but that's beyond the scope of this thread.)

Charlie followed up with a second, short note:

I suddenly remember that when I was a toddler over half a century ago my German mom taught me the nursery rhyme Schmetterling du kleines Ding. And judging from the number of versions on YouTube this ditty hasn't sunk into oblivion (yet).

After reading Charlie's first set of comments, I was prompted to wonder just what the relationship between schmetter(n) and Schmetterling, if any, might be. From my Germanic Studies colleagues, I received the following replies.

Christina Frei:

The word Schmetterling has another origin and nothing to do with "schmettern/zerschmettern.

The German word "Schmetterling" was coined for the first time in 1501 from the Slavic-based East-Middlegerman word "schmetten" which means heavy sour cream; cream (milk) referring to the fact that this type of animal was attracted to heavy cream and when cream was beaten to butter — hence the English butterfly.

From Ed Dixon:

Yes "zerschmettern" means to smash and "schmettern" has a similar meaning but can be used in other contexts as, e.g., "to belt out a song." However, in Middle High German according to Duden "schmettern" comes from "smetern" which meant "klappern" (to clatter, rattle, flap).

Another colleague suggested:

The prefix "zer" means completely or thoroughly. A butterfly is something, a little thing ("ling"), that shakes and flutters. Something that is zer-schmettert is shaken up so much as to be smashed.

From a German friend who was explaining the meaning of schmetter(n):

Donald Trump schmettert his anger about Cruz to NYT.

I zerschmetterte an entire Meissen coffee service when I fell into it.

The birds schmettern a song of happiness/excitement.

The boy schmetterte with/on his trumpet.

—

To forcefully throw, sling, or strike something WITH A LOUD CRASHING NOISE.

It's the NOISE and force of something which schmetters.

From Don Ringe:

So it turns out that Seebold has reconsidered Eng. _butterfly_. I quote from the 23rd ed. of Kluge's Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache (1995), rev. by Elmar Seebold:

"Das Wort [Schmetterling] gehört zu _Schmetten_ 'Rahm' wie _Buttervogel_, ne. _butterfly_ usw. (weil sich Schmetterlinge gerne auf Milchgefäße setzen). Darauf weisen for allem mundartliche Bezeichnungen wie _Milchdieb_, während sonst auch ein Anschluß an _schmettern_ (in bezug auf das Schlagen der Flügel) denkbar wäre."

As for _schmettern_ 'beat', he figures it's onomatopoeic, which is highly likely.

What I find odd about all of this is that, although my German is not very good (not quite schlecht, but certainly far from schön), the following meanings all seem to sound just right: "-ling" = something small and cute; "zer-" = thoroughly, completely; "schmetter" = flutter, beat. That is completely apart from any knowledge of the origins and etymology I may have gained in the course of preparing this post and the one about the lovely word Schmetterling that I had so much fun with a couple of weeks ago.

[Thanks to Nathan Hopson, Hiroko Sherry, Cecilia Segawa Seigle, Bethany Wiggin, David Spafford, Alfredo Cadonna, Heidi Krohne, Tomoko Takami, and Paolo Francalacci]