Of precious swords and Old Sinitic reconstructions, part 4

Language Log 2016-03-24

Previous posts in the series:

- "Of precious swords and Old Sinitic reconstructions" (3/8/16)

- "Of precious swords and Old Sinitic reconstructions, part 2" (3/12/16)

- "Of precious swords and Old Sinitic reconstructions, part 3" (3/16/16)

As mentioned before, the following post is not about a sword or other type of weapon per se, but in terms of its ancient Eurasian outlook, it arguably belongs in the series:

- "Of felt hats, feathers, macaroni, and weasels" (3/13/16)

From Peter Kupfer:

Concerning your remarks about "swords", I remembered the word kertte in Tocharian B and similar in Avestan mentioned in your book on the Tarim mummies, p. 310-311. It is very similar to Chinese jian 劍, which must have an old pronunciation something like ken/kiäm or, according to its phonetic component, even including an L-sound, corresponding to the original R.

See the long and detailed entry, including etymological notes, with possible cognates in Gothic, Old Norse, and Old English, in Douglas Q. Adams, A Dictionary of Tocharian B (rev. and greatly enlgd.), p. 211.

Juha Janhunen:

Hungarian also has kard 'sword', apparently from an Iranian source (? – can't check this at the moment).

Nicholas Sims-Williams:

I'm in Delhi, without reference books, but I think Toch. B kertte is reckoned to be an Iranian LW. At any rate the root must be what in Iranian is KART "to cut". Personally, I don't see any significant similarity to the Chinese form mentioned.

Hannes Fellner:

The the B-S reconstruction for 劍 (jiàn) is MC kjaemH < OC *s.kr[a]m-s.

John Bentley:

Baxter and Sagart's new reconstruction of Old Chinese reconstructs jian as *s.kr[a]m-s. I think Schuessler probably has something like *kam. The -tte bothers me, unless it is some kind of suffix in Tocharian B/Avestan. If so, then it may have been dropped when the word was imported into OC, but that's a wild guess. I don't have Schuessler's Old Minimal Chinese dictionary at hand (it's at the office), but generally Schuessler and B/S are pretty close in their reconstructions.

Asko Parpola:

The Tocharian word kertte 'sword' is related to several Sanskrit words meaning 'knife, dagger': karttarī, karttarikā, kṛntatram, kṛntanikā. These are derivatives from the root kart- present kṛntati (Rigveda) 'to cut (off)', from PIE *(s)kert- (Lithuanian kertù 'to cut off').

Another Sanskrit word for 'sword' is kṛpāṇa-, kṛpāṇī- (the word used by the Sikhs of their dagger), probably from PIE *(s)kerp- 'to cut' (Lithuanian kerpù 'to cut', Latin carpo 'to pluck').

The roots *(s)kert- and *(s)kerp- seem to be enlarged from the root *(s)ker- 'to cut' (Nordic skera 'to cut', Greek keírō 'to shear').

Proto-Samoyed seems to have an IE loanword in *kǝrǝ 'knife' (Juha's reconstruction in Janhunen 1977: 54).

I also want to refer to what Herodotus (4,62) tells about the Scythian "rites paid to Ares [the god of war]."

In every district, at the seat of the government, there stands a temple of this god, whereof the following is a description. It is a pile of brushwood, made of a vast quantity of faggots, in length and breadth 600 yards; in height somewhat less, having a square platform upon the top, three sides of which are precipitous, while the fourth slopes so that men may walk up it. Each year 150 waggon-loads of brushwood are added to the pile, which sinks continually by reason of the rains. An antique iron sword [akinákēs sidḗreos … arkhaîos] is planted on the top of every such mound, and serves as the image of Ares; yearly sacrifices of cattle and of horses are made to it, and more victims are offered thus than to all the rest of their gods. When prisoners are taken in war, out of every hundred men they sacrifice one, not however with the same rites as the cattle, but with different. Libations of wine are first poured upon their heads, after which they are slaughtered over a vessel; the vessel is then carried up to the top of the pile, and the blood poured upon the scimitar. While this takes place at the top of the mound, below, by the side of the temple, the right hands and arms of the slaughtered prisoners are cut off, and tossed on high into the air. Then the other victims are slain, and those who have offered the sacrifice depart, leaving the hands and arms where they may chance to have fallen, and the bodies also, separate" (translated by George Rawlinson, 1860).

The Turkic words discussed in the blog have been borrowed into Russian in various shapes, the most current word for 'dagger' being kinzhál, but also chingálishche, khandzhár, konchár, konchán.

Matt Anderson:

Baxter/Sagart give jian as *s.kram-s, and Schuessler as *kam, both of which seem reasonable to me, so it does fit pretty well (though the -tt- is a little odd).

I always associated the word jian with the south, which wouldn’t work that well (it often occurs in the context of Wu and Yue, and in the Chu ci, and it is written on many southern swords, such as the late Springs and Autumns Sword of Goujian 越王勾踐劍 from Hubei); and Schuessler also notes a likely southern connection ("[T] ONW kam || ‘Sword’ [Zuo, under the year 650 BC]. || [E] Etymology not certain. This mid Zhou period word could be derived from → yǎn4 剡覃 ‘sharp’ (implied by Wulff, Geilich 1994: 110, 263), the initial k- would then be a nominalizing prefix (§5.4). Alternatively, swords seem to have originated in the ancient southern state of Wú (Sūzhōu area), which was famous for its sword smiths. From there the word, of unknown provenance, may have entered OC as well as PVM as *t-kiəm [Ferlus].”).

However, the earliest probable example of the word that I’ve been able to find so far comes from the Western Zhou Shitong ding 師同鼎, from Zhouyuan, in Shaanxi. If this graph, written 鐱 (as are many of the southern examples of characters writing jian) in fact writes the word jian, that makes a connection with parts west much more likely. It appears in a list of metal objects, so it really does seem to be the right word.

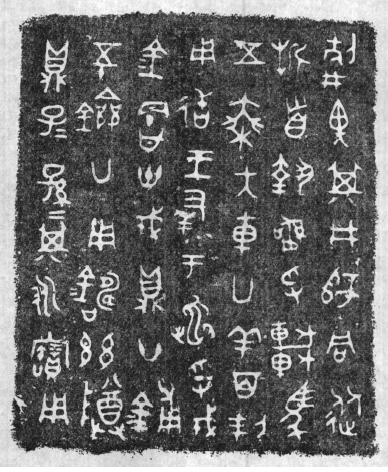

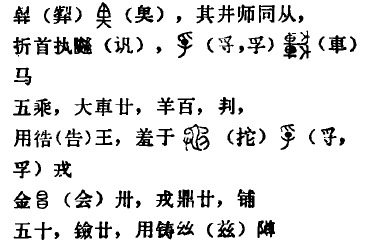

Here is the inscription, taken from Wenwu 1982.12:

The image of the transcription cuts off the last line, which should be:

鼎子子孫孫其永寶用

This is at least a start for considering Peter Kupfer's suggestion that the most common ancient Chinese word for "sword", namely jiàn 劍, might have a corresponding IE parallel.

There are at least two more posts to come in this series.

[Thanks to Chris Button and Mick Hunter]