(South) Korea bashing

Language Log 2017-03-14

Following up on these two recent posts:

- "Hate" (3/8/17)

- "No Japanese, South Koreans, or dogs" (3/8/17)

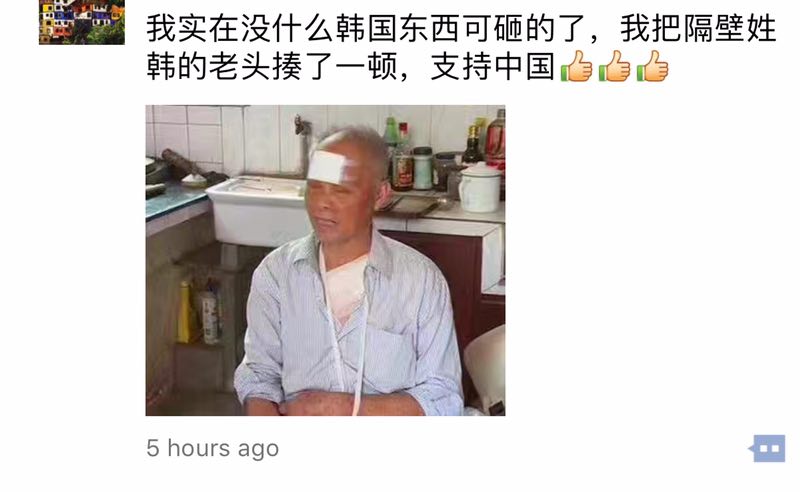

The Chinese characters above the photograph say:

Wǒ shízài méi shénme Hánguó dōngxi kě zá de le, wǒ bǎ gébì xìng Hán de lǎotóu zòule yī dùn, zhīchí Zhōngguó

我实在没什么韩国东西可砸的了,我把隔壁姓韩的老头揍了一顿,支持中国

"I really didn't have any (South) Korean things left to smash, so I gave the old guy surnamed Han* next door a beating to support China".

*[VHM: Hán 韩 was the name of an ancient state which existed from 403 to 230 BC in what is now Shanxi and Henan; it also forms part of the name of the modern country of (South) Korea — Hánguó 韩国.]

As explained in the earlier posts, Hánguó 韩国, in current parlance, refers specifically to South Korea. Hán 韩 is also an ethnic Hàn 汉 surname (don't get confused — different tones, different characters).

Of course, the above microblog post constitutes a kind of black humor, but South Koreans in China are receiving genuine threats and feeling concerned about their safety. The following is from one of China's most "authoritative" newspapers:

"South Koreans in China fearful as rumors about safety spread, ties worsen" (Global Times, 3/9/17)

Grammatical Notes

When I initially transcribed the long Chinese sentence above, I made a typo on the penultimate character of the first clause, mistyping 的 as 得. That's very easy to do, because they are both pronounced "de", are both very high frequency characters, and are both grammatical particles that properly occur in that position (between a verb and the clause / sentence final particle le / liao 了). But substituting de 得 for de 的 makes a world of subtle difference in the clause.

In fact, both clauses can roughly be translated as "I don't have anything Korean that I can smash". However, because of the different de 得/ de 的 and the different pronunciation and usage of le / liao 了, there is a significant disparity in the implications depending on whether de 得 or de 的 is used.

In "Wǒ shízài méi shénme Hánguó dōngxi kě zá de liǎo 我实在没什么韩国东西可砸得了, it means there is nothing Korean that I am able to smash, but the reason is unknown. Maybe all the Korean things the speaker owns are so important or so expensive that he / she cannot or dare not smash them. Or maybe all the Korean things the speaker owns are so huge and solid that he / she wouldn't be able to destroy them even if he / she tried to do so. In any case, "V de liǎo 得了" indicates that the subject of the sentence has the ability to carry out the action (verb). So, ”méi shénme 没什么 noun kě 可 V de liǎo 得了“ means "there is nothing the subject can verb". In this case, the speaker simply doesn't have anything South Korean around or left that he / she thinks he / she can smash, and we don't know the reason.

However, "Wǒ shízài méi shénme Hánguó dōngxi kě zá de le 我实在没什么韩国东西可砸的了, with de 的 instead of de 得, the clause means that I have smashed every South Korean thing at my disposal, so there's nothing South Korean left for me to smash. This pattern "méi shénme 没什么 noun kě 可 verb de le 的了" indicates "there's nothing left for the subject to verb".

Here are some example sentences employing the kě 可 plus Verb plus de 的 (kě 可 Verb de 的) construction, which is similar to the English expression "have something to do", or "doable", or "be worth doing".

Wǒ méiyǒu shénme dōngxi kě chī de 我没有什么东西可吃的 (“I have nothing to eat” or "I do not have anything that is eatable")

Zhèlǐ méishénme kě mǎi de 这里没什么可买的 ("There is nothing to buy here" or "Nothing here is worth purchasing")

Wǒ xiànzài méishénme kě zuò de 我现在没什么可做的 (“I have nothing to do now”)

Thus, "kě 可 Verb de 的" actually makes the verb function either as a noun or an adjectival component in the whole clause / sentence. It is grammatically correct to say "Wǒ méiyǒu shénme kě chī de dōngxi 我没有什么可吃的东西" ("I don't have anything to eat"). The post-position of this adjectival component is for emphasis (something like "I don't have anything at all to eat" or "I really don't have anything to eat" or "I truly don't have anything that is eatable / worth eating").

So it's just as well that I made that typo (de 得 for de 的), since it has prompted me to expatiate upon the subtle nuances of the "kě 可 Verb de 的" construction, which is something I might not have done otherwise.

Speaking of subtle nuances, I have to account for one more part of the first clause of the original long sentence from the microblog post cited above, viz., le 了. That's called "change of state le 了". This is something I learned very early in First-year Mandarin, and it has stuck with me indelibly ever since. This "change of state le 了" implies that there is a new situation that is different from the one that existed before. Hence,

Wǒ shízài méishénme Hánguó dōngxi kě zá de 我实在没什么韩国东西可砸的 (“I really do not have any South Korean things to smash”)

BUT

Wǒ shízài méishénme Hánguó dōngxi kě zá de le 我实在没什么韩国东西可砸的了 (“I really do not have any more South Korean things to smash”)

These tiny, little grammatical particles in Sinitic languages exert an enormous influence in conveying the overall meaning of clauses and sentences that is disproportionate to their size. I will discuss their role in Cantonese, where they are even more numerous than in Mandarin, at greater length in a separate, forthcoming post.

[Thanks to Melvin Lee, Fangyi Cheng, Jing Wen, and Yixue Yang]