Pitch contour perception

Language Log 2017-08-28

Listen to this brief four-syllable phrase, and answer a simple question:

once the eggs hatch

Your browser does not support the audio element.

Is the end of the last sylllable ("hatch") higher or lower in pitch than the start of the first sylllable ("once")?

If you're like most people, you hear "hatch" as ending somewhat higher than than the syllables that precede it, though it's also a little rough in voice quality.

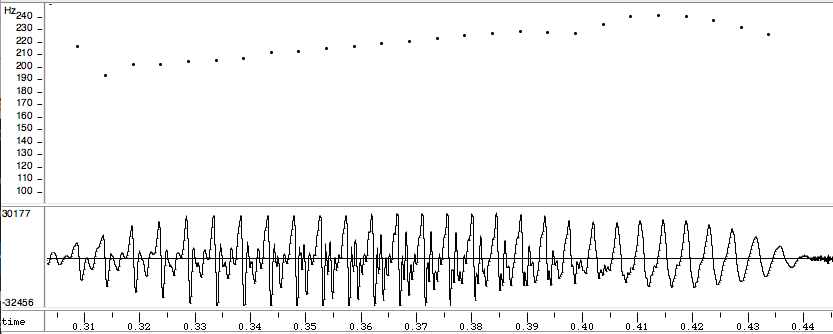

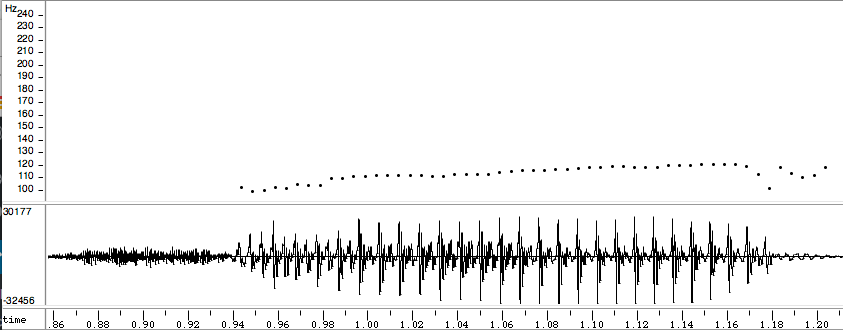

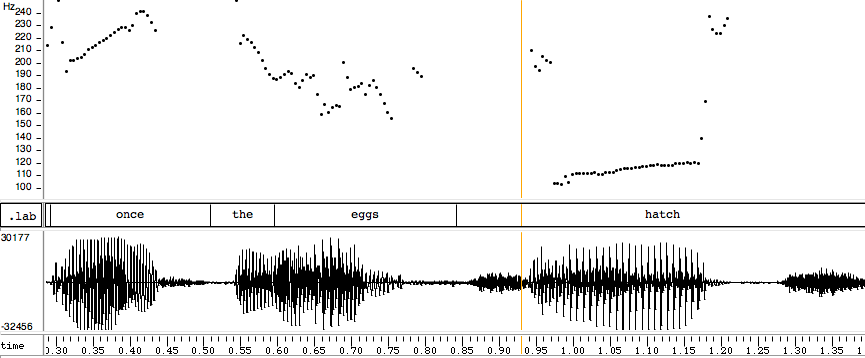

But in purely physical terms, the syllable "once" begins at about 200 Hz (= cycles per second) and ends at about 240 Hz, while the syllable "hatch" starts at about 100 Hz and ends at about 121 Hz, a full octave lower:

Thus an f0 track of the whole thing looks like this:

This is a good example of one of the reasons that (the psychological dimension of) pitch is not the same as the (physical dimenion of) fundamental frequency.

So what's going on here? Why does it sound (to most people) like "hatch" is a little higher than "once"?

In acoustic terms, we're hearing the second, fourth, sixth, … harmonics of "hatch" as a continuation of the first, second, third, … harmonics of "once". In the spectrogram below, I've outlined the third harmonic of "once" and the sixth harmonic of "hatch":

In articulatory terms, the octave shift in the last syllable (and also in part of the syllable "egg") is an example of something that's a feature of many oscillatory systems, which can undergo period doubling bifurcations as a natural consequence of the process that causes them to oscillate in the first place. This happens not only to speakers but also to wind, reed, and brass players, and also happens in many processes that don't involve humans at all.

On the perceptual side, this is related to the illusions known as Shepard Tones or Sherpard-Risset Glissandos, which are sort of auditory barber-pole illusions that also depend on octave-related ambiguities.

In the example phrase "once the eggs hatch", everything works out as it should, because what we hear is pretty much what the speaker intended.

But of course there are perceptual octave ambiguities in cases where there's no speaker intent to decode. Here's a tone glide that starts at 200 Hz and ends at 140 Hz, but sounds to most people as if it's rising throughout:

Your browser does not support the audio element.

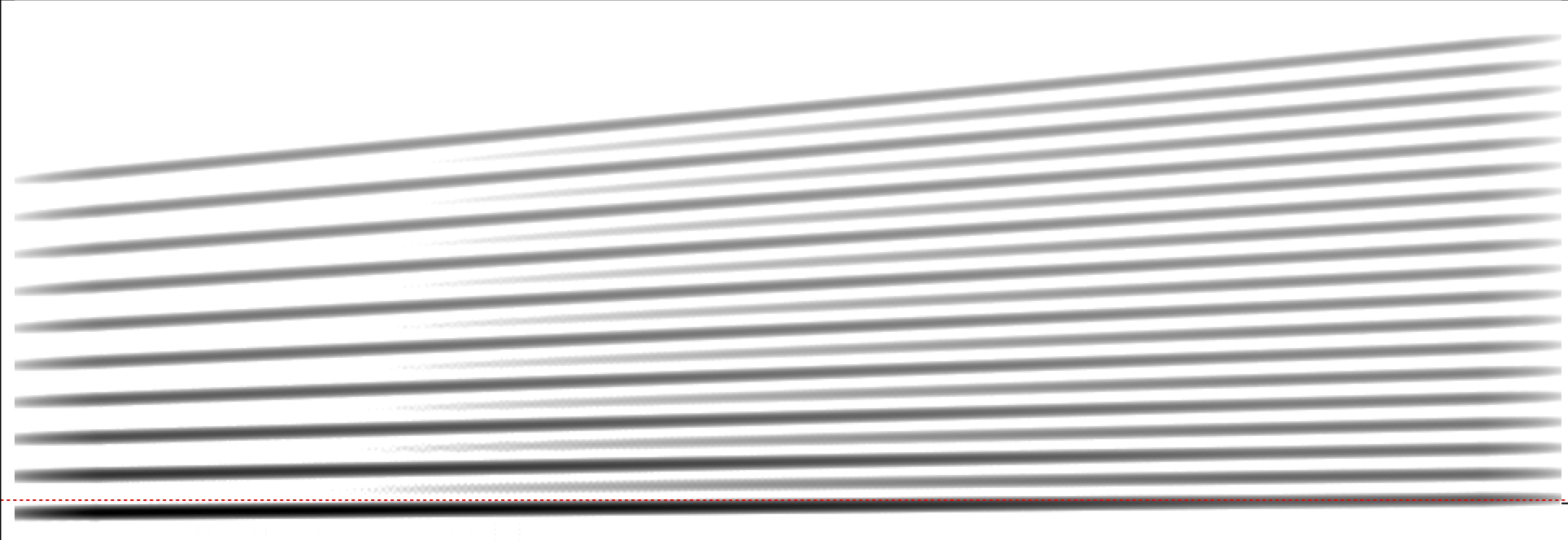

It blends a higher rise from 200 to 280 Hz with a lower rise from 100 to 140 Hz:

200-280100-140Your browser does not support the audio element.Your browser does not support the audio element.They're combined so that the first third is entirely the higher glide, and the last third is entirely the lower glide, while the middle third is a gradually shifting blend.

In the spectral domain, the blend looks like this:

The audio clip that we started this post with — "once the eggs hatch" — comes from an interview with Mary Gardiner, author of Good Garden Bugs, broadcast recently on You Bet Your Garden.

Here's the passage in context:

Your browser does not support the audio element.

With wasp parasitoids, they have what looks like a stinger, but is actually an ovipositor, or egg-laying organ, and so that ovipositor allows them to sting their prey and deposit an egg within it.

Some wasps or flies will lay their eggs on their prey, and then the larvae will hatch from those eggs and enter the insect, and some parasitoids even lay their eggs directly on plant material, hoping that their host will consume the eggs during feeding, and some of the undamaged eggs then hatch once they’re inside the pest.

Once the eggs hatch, one or more larvae will emerge per pest, and those larvae will consume the pest from the inside out, in an alien-like way, and then they will pupate either inside the host, or outside, sometimes on it, and then emerge as adults.