Real tone

Language Log 2018-02-07

In 'Tones for real", 2/5/2018, John McWhorter expresses his frustration as an American learner of Chinese: "How much must I attend to the damned tones in a sentence, as opposed to in citation, to really speak this language?"

As John very well knows (when he's not frustrated by the difficulties of learning a new language), his question has the same answer as the analogous questions "How much must I attend to the damned consonants/vowels in a sentence, as opposed to in citation, to really speak this language?" Fluent native speakers almost never use standard citation forms in fluent speech — sometimes the fluent versions are reduced or assimilated or dissimilated versions of the citation forms, and something they're just variably different. This is partly because informal speech is variably non-standard, but mostly because of the complex effects of linguistic and communicative contexts on the phonetic realization of phonological categories.

Unfortunately for language learners, these complex effects (though in some sense "natural") are different in different languages and dialects/varieties, so you can't just use your normal phonetic habits and expect the results to sound right. And we can use John's own pronunciation of English to illustrate some of these contextual effects.

In John's 2/6/2018 podcast with Glen Loury, "Being Black in 2018", I probed randomly near the start to find one of John's turns, and pulled out the opening phrase:

Well you know you're- you're not wrong, and you know what

Your browser does not support the audio element.

Let's skip the obvious things, like [jɪˈnoʊ] for "you know" and [jɚ] for "you're", and ask about the seventh and eighth syllables, "wrong and". If we listen to them out of context, they sound like [ˈrɔŋ.in] "wrongeen" (or maybe "wrongy"?):

Your browser does not support the audio element.

Why? Well, "and" becomes a reduced vowel plus [n], and the vowel assimilates across the nasal to the initial high front glide of the following "you".

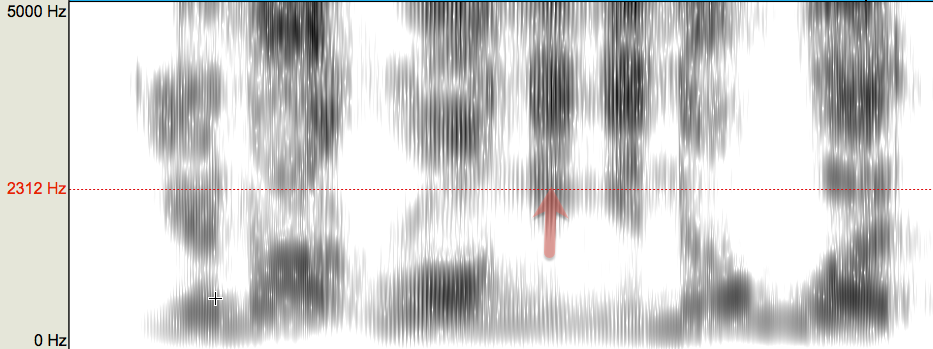

And the result really is phonetically a high front vowel — look at that F2:

Of course this doesn't mean that it's always OK to pronounce "and" as "een". It depends — and knowing what things like this depend on is one of the hardest parts of learning to speak fluently and idiomatically in English or in any other language. (This is frustrating for learners, but it keeps phoneticians in business…)

We could go into John's next few phrases and find similar examples of extreme contextual modulation of pronunciation — including plenty that involve only parts of content words — but I'll leave it there for now.

So what about the Chinese syllable that was frustrating John, zai4 在?

To get an idea about how Chinese speakers deal with zai4, let's look in a dataset that Neville Ryant, Jiahong Yuan and I put together a few years ago, "Mandarin Chinese Phonetic Segmentation and Tone". It consists of 7,849 cleanly-enunciated phrases from various Mandarin Broadcast News sources, divided (for purposes of machine-learning evalutation) into 300 test and 7,549 training examples. Obviously this is formal, standard, carefully-pronounced speech — but it's still language used to communicate, not "citation forms".

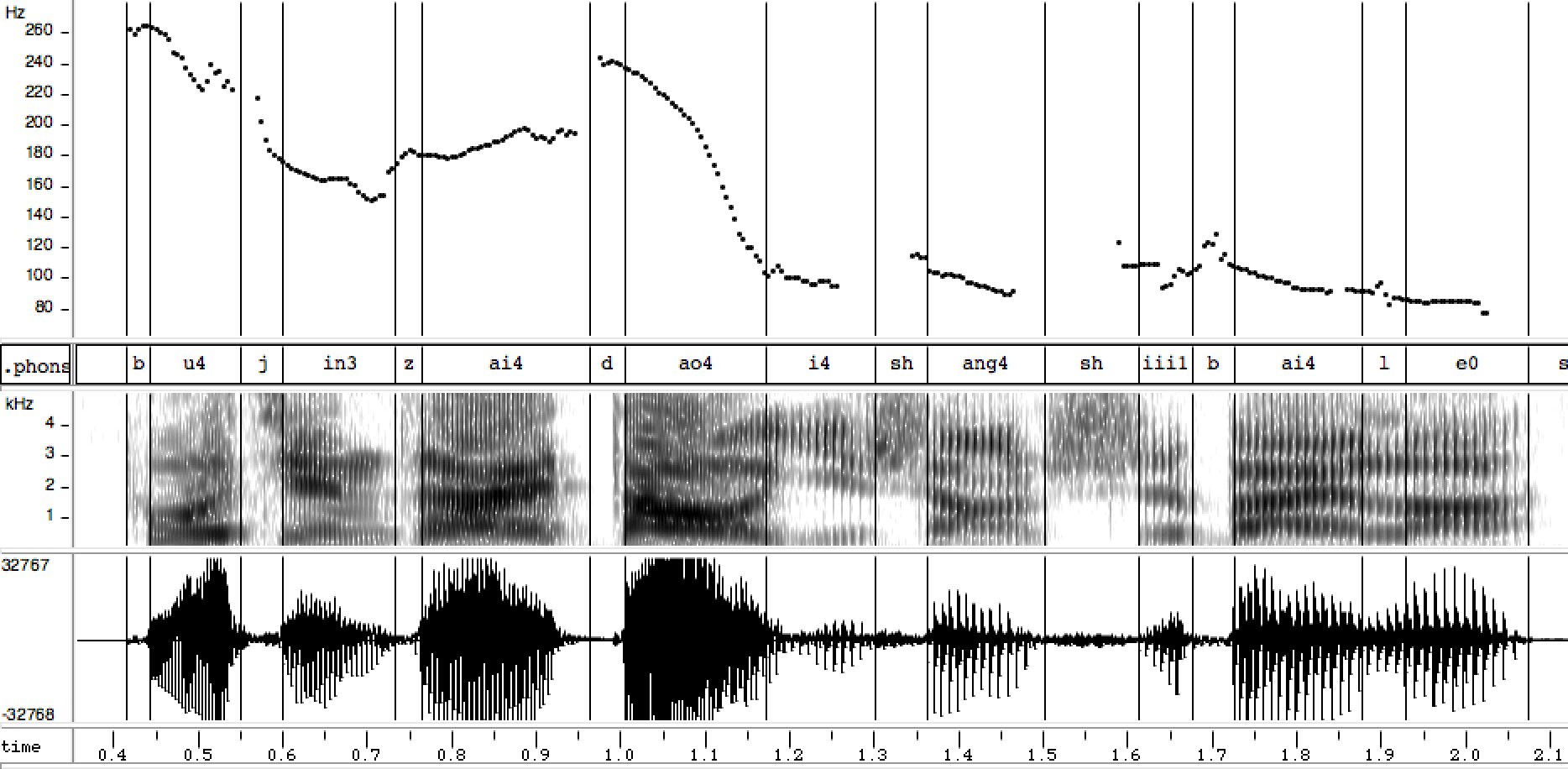

在 is a common-enough morpheme that it occurs 56 times in the 300 test sentences. The first one (in collating order of file names) is in the file test/chj000019 — which happens to include not only zai4, but five other tone 4 syllables. And as you can see, their realization in terms of pitch contours is quite diverse:

不仅 在 道义 上 失败 了 bu4 jin3 zai4 dao4 i4 shang4 shi1 bai4 le0

Your browser does not support the audio element.

In fact, weirdly enough, this zai4 is actually mid rising, although the canonical tone 4 pattern is high falling. Does this mean that it's always OK to pronounce zai4 as mid rising? Even if this example is not mislabelled, the answer is "obviously not — it depends". Presumably what it depends on in this case is that zai4 falls between jin3 (which ends low) and dao4 (which starts high), and is prosodically weak due to the syntax and semantics of the phrase.

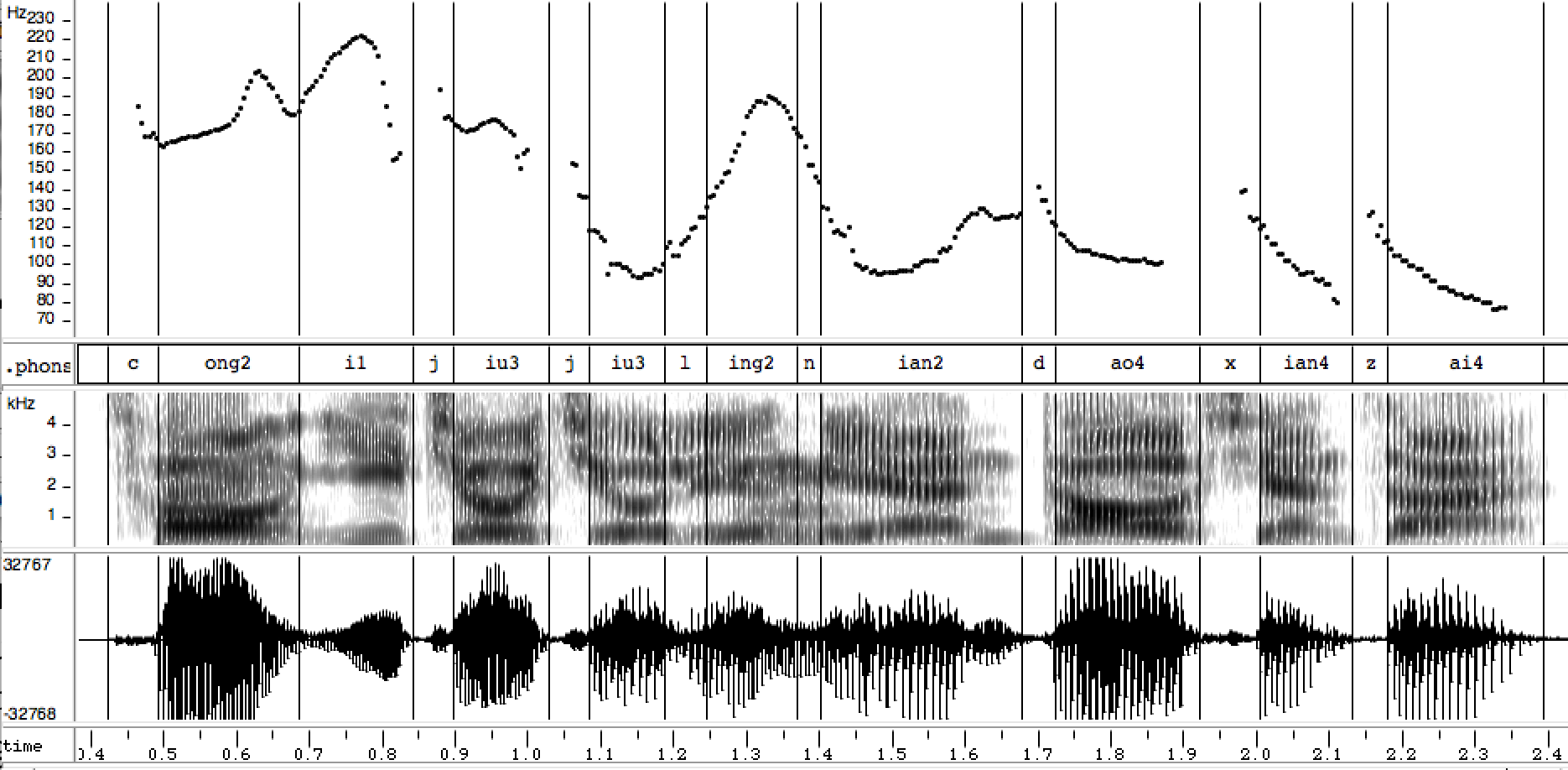

The next zai4 file has four tone 4 syllables at the end, closing with zai4:

从 一九九零年 到 现在 cong2 i1 jui3 jui3 ling2 nian2 dao4 xian4 zai4 Your browser does not support the audio element.

This time zai4 is actually falling, but just not so much, presumably because it's in a region of the phrase where the pitch range is compressed.

Of course, there are other features besides f0 that are involved in the perception and production of Mandarin tones, as discussed in the papers connected with that published dataset:

Neville Ryant, Jiahong Yuan, and Mark Liberman, "Mandarin tone classification without pitch tracking", ICASSP 2014

Neville Ryant , Malcolm Slaney , Mark Liberman , Elizabeth Shriberg , and Jiahong Yuan, "Highly Accurate Mandarin Tone Classification In The Absence of Pitch Information", Speech Prosody 2014

Or see this sideset from a 2015 presentation about those results — Tone Without Pitch.

For some discussion of factors influencing Mandarin tone 4 realization in tone4+tone4 words, see Wei Lai, Jiahong Yuan, and Mark Liberman, "Prosodic Strength Intrinsic to Lexical Items: A Corpus Study of Tone Reduction in Tone4+Tone4 Words in Mandarin Chinese", ISCSLP 2016.