On beyond the (International Phonetic) Alphabet

Language Log 2018-04-19

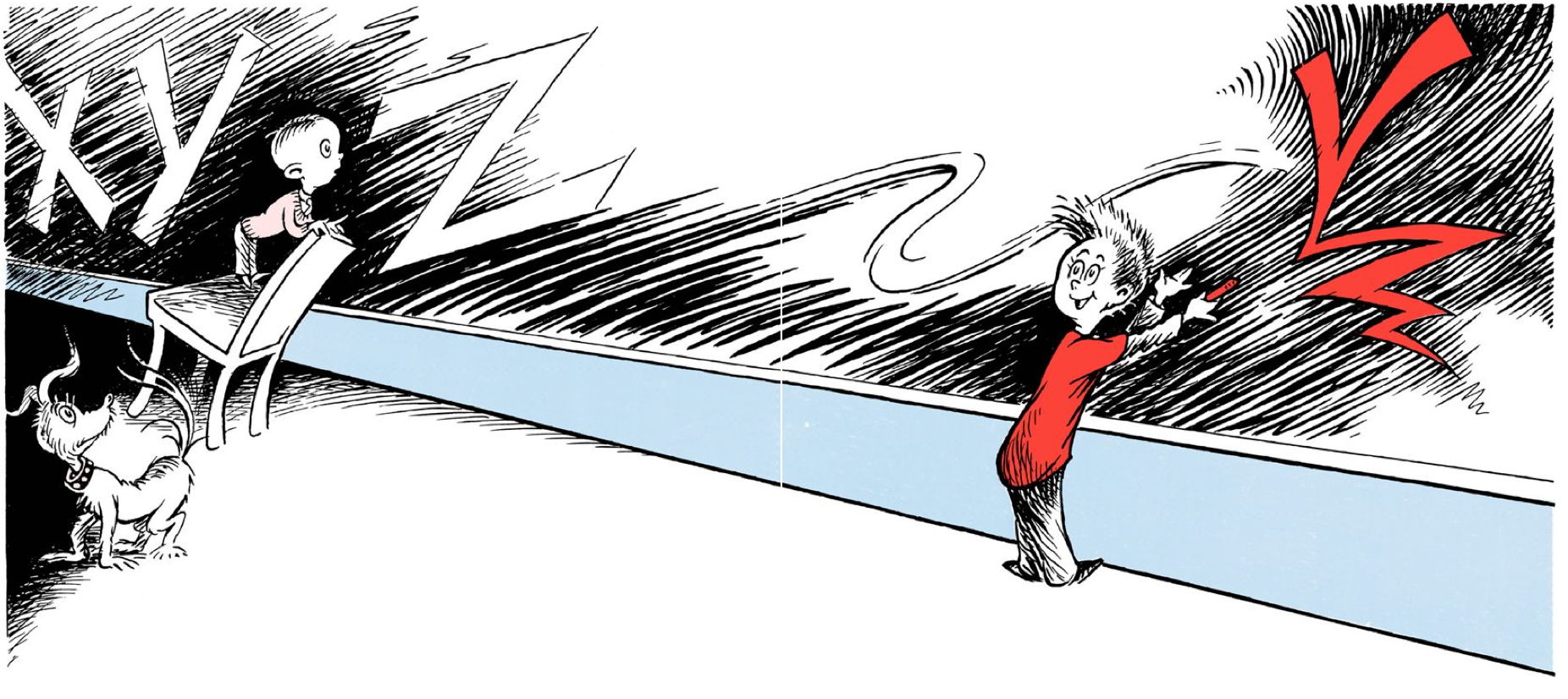

The International Phonetic Alphabet is a useful invention, which everyone interested in speech sounds should learn. But it's much less useful for actually doing phonetics than you might think. Whenever this comes up in discussion, I'm reminded of the Dr. Seuss classic On Beyond Zebra:

In the places I go there are things that I see That I never could spell if I stopped with the Z. I'm telling you this 'cause you're one of my friends. My alphabet starts where your alphabet ends!

Here's a simple example — listen, and contemplate:

(1)Your browser does not support the audio element.(2)Your browser does not support the audio element.And again:

(3)Your browser does not support the audio element.(4)Your browser does not support the audio element.Just a few more:

(5)Your browser does not support the audio element.(6)Your browser does not support the audio element.(7)Your browser does not support the audio element.Those are the seven renditions of sentence SX437, "They used an aggressive policeman to flag thoughtless motorists", from the TIMIT Acoustic-Phonetic Continuous Speech Corpus, created at SRI, TI, MIT and NIST between 1987 and 1990.

And among the many things happening in these examples, the point of interest to us today is the pronunciation of the final /sts/ sequence in motorists, which varies from a full s + t-closure + s sequence in (1):

(1)Your browser does not support the audio element.

…through successively weaker approximations to the /t/ gesture in (2), (3), and (4):

(2)Your browser does not support the audio element.

(3)Your browser does not support the audio element.

(4)Your browser does not support the audio element.

…through successively shorter uninterrupted /s/ regions in (5), (6), and (7):

(5)Your browser does not support the audio element.

(6)Your browser does not support the audio element.

(7)Your browser does not support the audio element.

In case you're tempted to think that the problem here is sloppy speaking by ordinary unprofessional talkers, here's an example from a consummate professional voice. Terry Gross is the host of the Fresh Air radio interview program, and this is how she starts her 3/16/2015 interview with Daniel Torday:

Your browser does not support the audio element.

Your browser does not support the audio element.

And this is not an aberration. In words like motorists, artists, activists, exists, consists, , etc., both professional speakers and ordinary Americans exhibit a similar palette of outcomes for the word-final /sts/. There might be a well-defined silent stop region separating two [s] fricatives, or there might be a region of variably-lowered amplitude in the middle of a fricative, or there might a variable-length fricative without any medial amplitude modulation at all. (And it's worth noting that in fluent speech, the full [sts] variant is quite rare. There are just 4 full [sts] variants out of 61 word-final /sts/ examples in TIMIT, for example (6.6%). In fluent reading of continuous passages the proportion is generally to be lower than that, and it's lower still in spontaneous speech. Overall, the uninterrupted [ss] — or [s]? — version seems to be the commonest case.)

So how should we transcribe these various variants of /sts/?

As far as I know, the IPA doesn't have any symbol for a lowered-amplitude region in the middle of a coronal fricative. We could go "on beyond (IPA) zebra" and invent one — maybe an otherwise unused letter like sigma σ, or maybe taking over one of Dr. Seuss's inventions, say spazz:

But that would probably be a mistake, at least if we interpret

[sts]  [sσs]

[sσs]  [ss]

[ss]  [s]

[s]

as necessarily representing qualitative symbolic distinctions rather than a continuum of degrees of lenition.

For one thing, as we continue on beyond phonetic zebra, we'll find that other variations in strength, timing and coordination of articulatory gestures seem to motivate literally thousands of additional "symbols":

As Dr. Seuss put it

Oh, the thing you can find If you don't stay behind!

But by inventing and deploying those symbols, we'd be giving premature answers to the really interesting and important questions.

My own guess is that the /sts/ variation discussed above, like most forms of allophonic variation, is not symbolically mediated, and therefore should not be treated by inventing new phonetic symbols (or adapting old ones). Rather, it's part of the process of phonetic interpretation, whereby symbolic (i.e. digital) phonological representations are related to (continuous, analog) patterns of articulation and sound.

It would be a mistake to think of such variation as the result of universal physiological and physical processes: though the effects are generally in some sense natural, there remain considerable differences across languages, language varieties, and speaking styles. And of course the results tend to become "lexicalized" and/or "phonologized" over time — this is one of the key drivers of linguistic change.

For more on this, see "Towards Progress in Theories of Language Sound Structure", in Brentari & Lee, Eds., Shaping Phonology, 2018.

[And yes, Dr. Seuss has been steering kids wrong all these years — duality of patterning ensures that a properly-designed alphabetic orthography can spell any real or possible word in a given language. But extending the alphabetic principle to phonetic interpretation is a mistake, in my opinion.]