Ampersand in Chinese

Language Log 2018-08-09

From Caitlin Schultz:

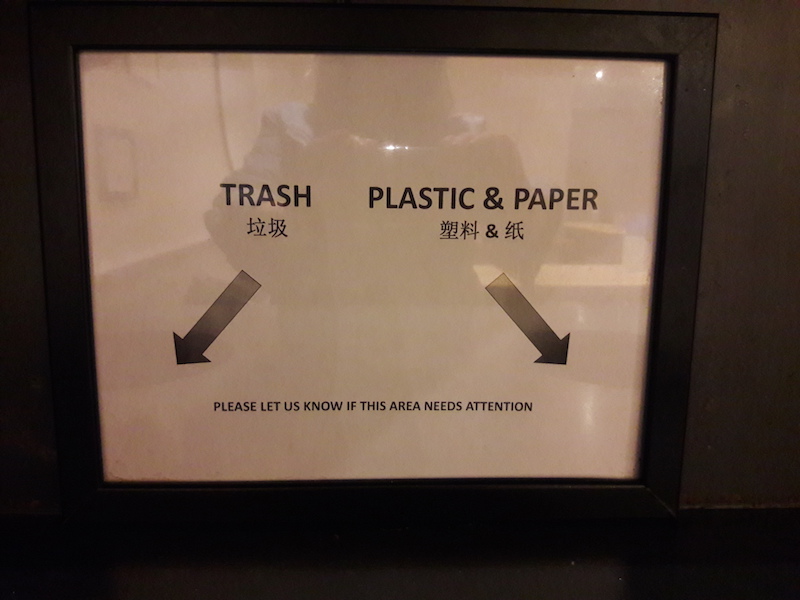

I was eating at a place called Yaso Tangbao in Midtown Manhattan recently and snapped these photos of Chinese characters and ampersands. I thought it was unusual!

Here's what the signs say in Chinese:

zhúlóng & tuōpán 竹笼 & 托盘 ("bamboo baskets & trays") lājī (PRC) / lèsè (Taiwan), sùliào & zhǐ 垃圾, 塑料 & 纸 ("trash, plastic & paper")

píngzi & guànzi 瓶子 & 罐子 ("bottles & cans")

There's no problem with the translations. The question is how to pronounce the ampersand.

The 卍 has already been present for four to five thousand years in territory that is now part of western China. Later, around four thousand years ago, it was reintroduced with Buddhism and also taken up by Taoism. We know how to pronounce it, viz., wàn. It can mean "swastika" or "ten thousand".

Ditto for "Q", "X", and many other originally non-Sinitic symbols that have been absorbed into the Chinese writing system.

Among other readings on this subject, see:

- "Creeping Romanization in Chinese" (8/30/12)

- "New radicals in an old writing system" (8/29/12)

- "Zhao C: a Man Who Lost His Name" (2/27/09)

- "A New Morpheme in Mandarin"

- Mark Hansell, "The Sino-Alphabet: The Assimilation of Roman Letters into the Chinese Writing System," Sino-Platonic Papers, 45 (May, 1994), 1-28.

- LIU Yongquan (Institute of Linguistics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences), "On the Problem of Chinese Lettered Words, Sino-Platonic Papers, 116 (May, 2002).

The earliest character I know of was introduced from the West more than four millennia ago:

☩ > wū 巫 ("shaman; witch, wizard; magician"), Old Sinitic *myag, a loanword from Old Persian *maguš ("magician; magi")

References

Mair, Victor H. 2012. "The Earliest Identifiable Written Chinese Character.” In Archaeology and Language: Indo-European Studies Presented to James P. Mallory, ed. Martin E. Huld, Karlene Jones-Bley, and Dean Miller. JIES Monograph Series No. 60. Washington, D.C.: Institute for the Study of Man. Pp. 265–279.

__________. 1990. "Old Sinitic *Myag, Old Persian Maguš and English Magician", Early China 15: 27–47.

Since the Chinese writing system is open-ended, there's no reason why symbols like "&" cannot become a part of it, but people who use them must have an associated sound in their mind when they write them down.