PSDS

Language Log 2014-03-30

Linguists are generally scornful of "eye dialect", in both of the common meanings of that term:

- As an "unusual spelling intended to represent dialectal or colloquial idiosyncrasies of speech", like roight for right or yahd for yard;

- As a "the use of non-standard spellings such as enuff for enough or wuz for was, to indicate that the speaker is uneducated".

The first kind of eye-dialect is seen as inexact ("you should use IPA") and the second kind is seen as snobbish. I'm generally more curious than censorious about both of these practices; but in any case, I recently saw a case of the first kind that struck me as especially interesting.

Rcently Clark DeLeon ("Fluffya tawks OK? Roight?", philly.com 3/23/2014) took up the piece by Daniel Nester ("The Sound of Philadelphia Fades Out", NYT 3/1/2014) that Joe Fruehwald criticized earlier here on LLOG ("Not So Fast with the Funny Fading Dialect Stuff", 3/4/2014).

What stuck with me about DeLeon's post was not what he had to say about Philadelphia speech, but a bit of Boston eye-dialect that he threw in along the way:

Boston still has a neighborhood accent that's easy to mimic and recognize. For instance, say PSDS out loud, speaking the individual letters real fast. (In Boston you would need these before you could try on a pair of pierced earrings.) Say it again, PSDS.

This joke/observation is not original to DeLeon — there's a post from 2004 that also mentions BSNDS for "bears and deers", CS for "Sears", GS for "jeers", PS for "pears", etc. I won't be surprised if Ben Zimmer can turn up an example from the 19th century.

But PSDS is a case where the use of eye dialect is worthwhile, in my opinion. It rings as true to me as it did to "Susan" back in 2009 (though I never had the specific experience she describes):

Oh yeah! I moved to the area when I was a little kid (about 30 years ago). A woman in a department store asked if I had PSDS. I said, "What is P.S.D.S.?" She replied, "You know, PSDS," grabbed an earlobe, and wiggled it back and forth. "Oh! Pierced ears!" That's exactly how it sounds to someone from the west coast!

And in addition to the obvious Boston-area r-lessness, the "PSDS=pierced ears" equivalence illustrates four or five important things about the phonetics and phonology of American English — and about phonetics and phonology in general.

1. Lenition of /t/ in the environment s_#V – i.e. word-final /t/ after /s/, before a following vowel-initial word.

Examples are "past actions", "most accomplished", "based on" — or "pierced ears".

This is related to the more general lenition of /t/ in the context C_#X, for which the sociolinguistic literature uses the (lamentably misleading) name "t-d deletion". There's also the lenition of /t/ in the context V#V ("put off", "at all", "fat Albert", …), and in fact the general lenition of syllable-final consonants.

But with specific relevance to this case, the word-final /t/ in cases like "pierced ears" has little or no aspiration following the release into the following vowel, so that the resulting CV transition sounds like /d/ rather than /t/. If this were not true, we'd have PSTS, not PSDS.

Here are a couple of examples from TIMIT:

The sentence is "Medieval society was based on hierarchies", and the first syllable should sound to you as if it might have been "dawn".

2. Syllable-final (and especially phrase-final) /z/ is usually voiceless, and thus distinguished from /s/ only by the duration of the preceding vowel (on average longer than before /s/, other things equal) and the duration of the voiceless fricative noise (on average shorter than for /s/, other things equal). This means that the /s/ in [ɛs] – the standard pronunciation of "S" — overlaps phonetically with the /z/ at the end of "ears".

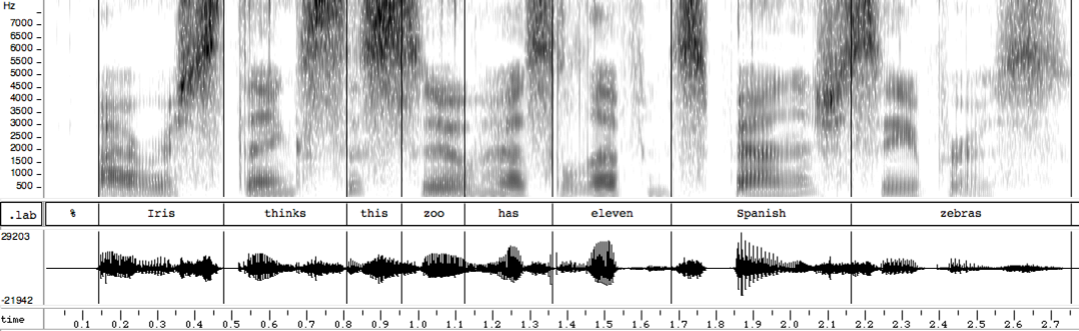

Here are a couple of TIMIT examples — versions of "Iris thinks this zoo has eleven Spanish zebras":

Spectrograms of the two audio clips, in which the voicing status of the final /z/ is clear:

3. The unstressed central (underspecified?) vowel assimilates to its context. As a result, the vocalic reflex of /r/ in "pierced" and "ears" — schwa between /i/ and /s/ or /z/ — is raised and fronted to the point that the [ɛ] of S is a good match.

4. Perception of word and syllable boundaries depends (only) on context-conditioned phonetic variation. And also,

5. Allophonic variation is gradient.

Therefore the four-word — and four-syllable — phonemic sequence

/ˈpi#ˈɛs#ˈdi#ˈɛs/

overlaps phonetically (in this variety of English) with the two-word phonemic sequence

/ˈpi.əst#ˈi.əz/

There's also something to be learned from the fact that Boston-area "ears" seems like (and is?) two syllables, while Boston-area "yard" seems like one. But I've got to be leave for the rest of PLC38.