ytš ḥṭ ḏ lqml śʿ[r w]zqt

Language Log 2022-11-10

Which being translated is "May this tusk root out the lice of the hai[r and the] beard".

You can read all about this object here: Daniel Vainstub et al., "A Canaanite’s Wish to Eradicate Lice on an Inscribed Ivory Comb from Lachish", Jewish Journal of Archaeology 2022. The abstract:

An inscription in early Canaanite script from Lachish, incised on an ivory comb, is presented. The 17 letters, in early pictographic style, form seven words expressing a plea against lice.

Or you can consult Oliver Whang's article in the NYT, "An Ancient People’s Oldest Message: Get Rid of Beard Lice", 11/9/2022.

The subhead: "Archaeologists in Israel unearthed a tiny ivory comb inscribed with the oldest known sentence written in an alphabet that evolved into one we use today."

A small quibble here is that the script in question is technically an abjad, not an alphabet — but "…written in an abjad that evolved into the alphabet we use today" would be inappropriately obscure for NYT readers. And it's common to use terms like "the Hebrew alphabet" or "the Arabic alphabet". Another small quibble is that there are graffiti in (a version of) the proto-Sinaitic script from Egypt, dated (by some) a few hundred years earlier than this marvelous comb. (Apparently the Egyptian inscriptions, apart from the dating uncertainties, are not totally deciphered and may not express full sentences.)

Unsurprisingly, much of the comb's coverage in the mass media is more misleading. Thus the headline for Mark Lungariello's article in the New York Post is "Oldest sentence in history discovered – warning of beard lice almost 4,000 years ago":

The oldest sentence written in the earliest known alphabet has been discovered – carved into an ivory comb which warned about head lice.

It's obvious that "the oldest sentence in history" must have been spoken many tens of thousands of years before any writing systems were invented …

Anyhow, the Vainstub et al. article will give you all of the inscription's details character by character:

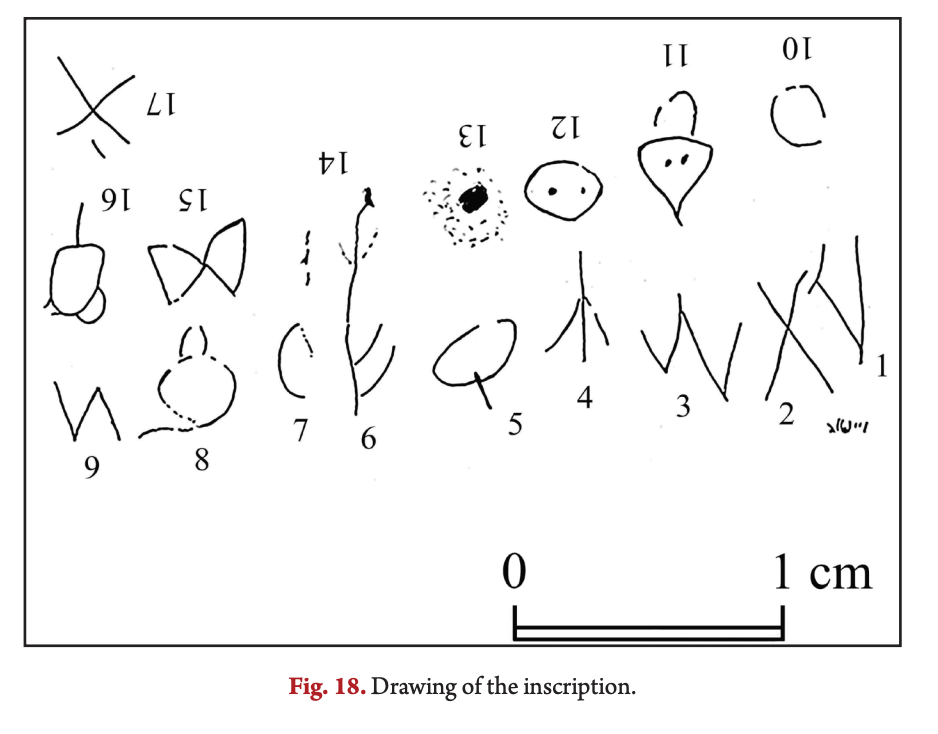

The inscription contains 17 tiny letters that vary in width from 1 to 3 mm, engraved on the not-completely-smooth surface of the comb. The letters form seven words that for the first time provide us with a complete reliable sentence in a Canaanite dialect, written in the Canaanite script.

Most of the letters survive to some degree, except for letter 13, which was totally damaged, and letter 14, of which only a few parts remain. The engraver did not maintain alignment of the letters or uniformity of their size. In the first row that he wrote, the letters become progressively smaller and lower. In this row the script runs from right to left, and when the engraver reached the edge of the comb, he turned the comb through 180° and wrote the second row from left to right, in such a way that the rows are arranged “heads on heads”, with the heads of the letters in the middle of the comb and the bases of the letters facing both lines of teeth. When the engraver reached the edge of the comb at the end of the second row, not enough space remained for another letter, and so he engraved it below the last letter of the row. Because of the change of orientation, both rows start on the same side of the comb, unlike in the boustrophedon method.

Here's their diagram of the inscription:

They go through the 17 letters in detail, one at a time. What they say about the first one:

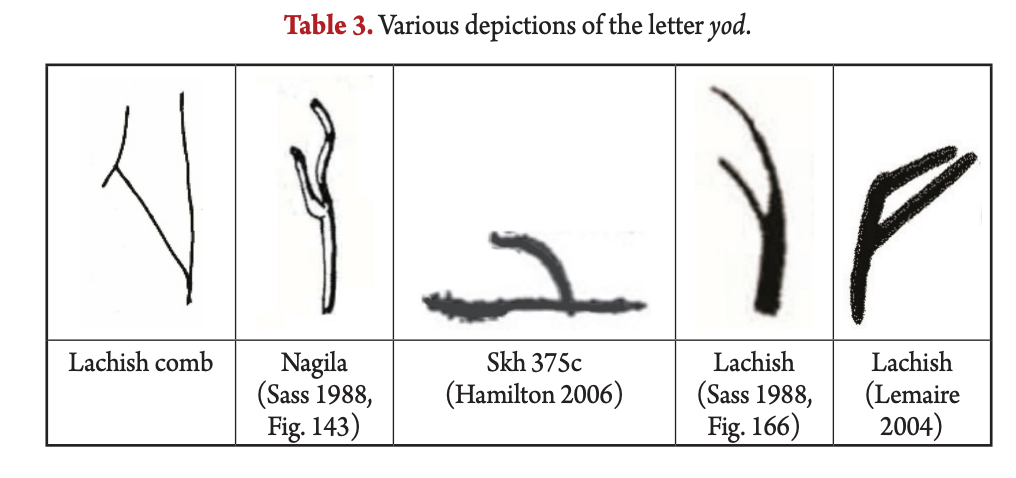

Letter 1. The letter is a standing “curved palm” yod (Hamilton 2006: 108–112) with considerable disproportion between its parts: the thumb, which was most probably engraved first, is longer than would be expected (Table 3). Yods executed in a similar fashion are known from Serabiṭ el-Khadem inscription 375c (Hamilton 2006: 377) and the Tel Nagila sherd (Sass 1988, Figs. 143–144). The stratigraphic dating of the Tel Nagila sherd is not entirely clear; initially it was dated tentatively to the end of the Middle Bronze Age or the beginning of the Late Bronze Age, but this is now controversial (Sass 2005: 159; Finkelstein and Sass 2013: 156).

Read the whole thing!