"Protester dressed as Boris Johnson scales Big Ben"

Lingua Franca 2019-10-22

Sometimes it's hard for us humans to see the intended meaning of an ambiguous phrase, like "Hospitals named after sandwiches kill five". But in other cases, the intended structure comes easily to us, and we have a hard time seeing the alternative, as in the case of "Extinction rebellion protester dressed as Boris Johnson scales Big Ben".

These two examples have essentially the same structure. There's a word that might be construed as a preposition linking a verb to a nominal argument ("named after sandwiches", "dressed as Boris Johnson"), or alternatively as a complementizer introducing a subordinate clause ("after sandwiches kill five", "as Boris Johnson scales Big Ben"). In the first example, the complementizer reading is the one the author intended, while in the second example, it's the preposition. But in both cases, most of us go for the preposition, presumably because "named after X" and "dressed as Y" are common constructions.

Interestingly, some commonly used parsers have more or less the opposite prejudice. Thus the Berkeley parser:

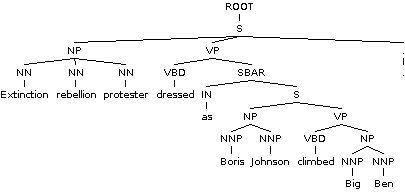

In the second example, the Berkeley parser analyzes scales as a plural noun, but still places it in the structure appropriate for a verb:

If we substitute climbed for scales, the part of speech problem is fixed, but the structure is still the wrong one:

The Stanford parser acts in a similarly inhuman way in the first example:

(ROOT (S (NP (NNS Hospitals)) (VP (VBD named) (SBAR (IN after) (S (NP (NNS sandwiches)) (VP (VBP kill) (NP (CD five)))))) (. .)))

In the second example, it makes a slightly different choice, deciding that scales is a proper noun, and that "Boris Johnson scales Big Ben" is stacked-up noun phrase like "North Dallas tornados property damage".

(ROOT (S (NP (NNP Extinction) (NN rebellion) (NN protester)) (VP (VBD dressed) (PP (IN as) (NP (NNP Boris) (NNP Johnson) (NNP scales) (NNP Big) (NNP Ben)))) (. .)))

If we prevent this error by substituting climbed for scales, we're back with the complementizer reading:

(ROOT (S (NP (NNP Extinction) (NN rebellion) (NN protester)) (VP (VBD dressed) (SBAR (IN as) (S (NP (NNP Boris) (NNP Johnson)) (VP (VBD climbed) (NP (NNP Big) (NNP Ben)))))) (. .)))

Our intuition — mine, anyhow — is that our analysis is guided by a combination of pattern frequency and common sense. Thus we have trouble with the first example, because "Hospitals named after sandwiches" fits our "X named after Y" pattern well enough to lock in that reading — but the result makes no sense. And we do the right thing with the second example, because "protested dressed as Boris Johnson" fits the "X dressed as Y" pattern, and this time the result works out.

The parsers apparently don't have — or don't use — those patterns. Which is ironic, since such parsers approximate the concept "makes sense" in terms of lexical co-occurrence rather conceptual coherence. More modern NLP systems have more elaborately trained expectations about lexical co-occurrences. But conceptual coherence is still a problem, as underlined by the Winograd Schema Challenge results.