The light flickers

Pharyngula 2024-07-06

When I think about my childhood, I founder on the fact that memory is not linear, it’s not complete, and most of what remember is a wash of general feelings and confabulations anchored by brief, vivid flashes of specific moments that are lit up by unforgettable events. I was fortunate that much of that vague blur of background events was made up of kindness and love, of a stable and affectionate home, but that also means that the specific memories are scarce and hard to salvage from the general wave of goodness, and are difficult to place in a clear sequence, unless they’re attached to a recorded historical event.

One such memory is from March of 1964. I was seven, attending Kent Elementary, and I was alone, walking across the playground, which was conveniently across the street from my house. I was alone because I had no friends; we had moved to a new house and a new school, which was a common event, since my parents were struggling economically, and we moved roughly once a year, as they tried to simultaneously move out of the poor places they were trapped in and build a stable home for their family. That’s part of the background noise of my childhood memories, trying to remember which house we were living in when some more interesting thing happened. My memory warehouse is built of one rental after another, creating a ramshackle sequence that stitches events together.

The bright moment that illuminates this one memory is the Great Alaskan Earthquake of 1964. I was walking, alone, when suddenly my legs were swept out from under me, and I was on my knees wondering why I was still wobbling and how the earth beneath me wasn’t stable anymore. I looked up at the school and saw a crack had formed in its south wall. I looked to the right at my house, and saw a few bricks fall from the chimney. That was all — this was near Seattle, far from the epicenter — so damage was light, and maybe the worst of it for me was the abrupt loss of certainty. Not even the Earth could be trusted.

That house, though…

There is another moment picked out by my strobe light of remembrance. I know we were feeling a general anxiety — Dad had lost another job, we’d had to move from a fairly nice housing development on the hill to an older, smaller house in town, and Dad was often absent, because he’d be working two jobs to make ends meet. Mom was holding the family together, and we kids felt secure no matter what, because she took care of us. There was me, the oldest, my brother Jim who was about a year younger, and then in rapid fire sequence, my sisters Caryn and Tomi. My little brother Michael had been born recently, I think — he was a small bundle of babiness without a personality yet. My mother was a paragon of maternal devotion. She loved kids, deeply and sincerely, later in life she would just melt into a beaming beacon of pure love when she would hold her grandkids. It was the same in our childhood and in her youth (she married young, and was only in her twenties at this time), and she was always quiet and tolerant and treated us little beasts kindly. There was discipline, but it wasn’t by violence or anger or yelling. We all knew that the worst thing we could ever do is disappoint Mom.

There is another moment picked out by my strobe light of remembrance. I know we were feeling a general anxiety — Dad had lost another job, we’d had to move from a fairly nice housing development on the hill to an older, smaller house in town, and Dad was often absent, because he’d be working two jobs to make ends meet. Mom was holding the family together, and we kids felt secure no matter what, because she took care of us. There was me, the oldest, my brother Jim who was about a year younger, and then in rapid fire sequence, my sisters Caryn and Tomi. My little brother Michael had been born recently, I think — he was a small bundle of babiness without a personality yet. My mother was a paragon of maternal devotion. She loved kids, deeply and sincerely, later in life she would just melt into a beaming beacon of pure love when she would hold her grandkids. It was the same in our childhood and in her youth (she married young, and was only in her twenties at this time), and she was always quiet and tolerant and treated us little beasts kindly. There was discipline, but it wasn’t by violence or anger or yelling. We all knew that the worst thing we could ever do is disappoint Mom.

There was stress in the household, though. Mom and Dad would sometimes argue, quietly. I know that over the years Mom would suggest that she could help by taking a part-time job, which would also allow her out of the house and that swarm of littles she was caring for, but my Dad did not like that idea. I think that he felt his role as the breadwinner was a key part of his identity. The patriarchy, you know.

This one painfully sharp memory from that time in that house…I was sitting on the sofa in the living room, reading a comic book, and Jim was sitting next to me, watching TV. It was quiet and calm, my parents and my sisters were somewhere in the back of the house. Suddenly there were shrieks from my little sister, and they ran into the living room, jumping up and down and waving their arms in hysterics, screaming in their piping little voices, “Dad hit Mom! Dad hit Mom!” over and over again.

This was unimaginable. If there was anything we knew, it was that Mom and Dad loved each other and loved us, and that good people didn’t hit. This was worse than the earthquake.

A few minutes later, Mom swept into the living room, where we kids were stunned and paralyzed, carrying a suitcase and the baby. She took my sisters, went out the door, and walked away to stay with her parents. She didn’t say a word to us boys. A little later, Dad came out and took us away to his mother’s house.

It was a confusing situation. I remember being oddly proud of Mom for standing up for herself so decisively, for being so damned strong and fierce. Mom was always quiet and shy, but she had lines you did not cross, and that’s how you do it, with unhesitating confidence. That was strength.

But at the same, the little boy in me was wondering…why didn’t she take me or Jim? How had we disappointed her? What did I do wrong?

That began the worst period in my life. We lived with Grandma Myers, who was wonderfully generous in her sympathy and kindness, but what I remember of that time was that it seemed to be constantly raining and the skies were made of lead (it was Seattle, after all) and I was trudging from Grandma’s house to school and back again with the rain to hide the tears erupting from my face. I could walk over to visit Mom now and then — my two sets of grandparents lived only a few blocks apart — but Dad was mostly missing. His response to embarrasment or shame was always to draw apart and hide in his work.

(huh…I wonder where I got that trait from?)

The story has a happy ending, at least. This is another crystal clear moment in my memory.

One morning, we walked over to visit Mom, and Grandma Westad was in a fury — we heard the “Nehmen!”s and angry sighs of exasperation as we walked in the door. Mom was sitting at the dining room table while Grandma was waving a pair of men’s underwear and berating her: “I found this on the stairs! Has that boy been sneaking over in the night?!?”

Mom didn’t say a word. You should have figured out by now that my family was just generally quiet and didn’t need to say much. But she looked up at me and gave me a small smile, a Mona Lisa smile, and looked so happy. I knew. Mom and Dad still loved each other, the world had stopped shaking, we were going to get back together again.

Reconciliation wasn’t instantaneous. In years to come, though, Mom would learn to drive. She’d get her GED. Later still she’d get a job, finally, working at Boeing and wiring planes and assembling missiles, the most un-Mom job I could imagine. And most importantly, Dad learned to always control his temper with Mom and the rest of us. All was well again.

Another flash of memory: Dad died in 1992. I’m at the funeral home. Mom is in tears. I went to the room with his body. I tried to give him a hug, something we never did often enough. So cold, so hard, his barrel chest felt huge, like I was trying to hug an oak tree. I walked back to Mom, who was concerned and asked if I was OK. She was wrecked, but she was asking about me? Mom, I learned to be strong from you.

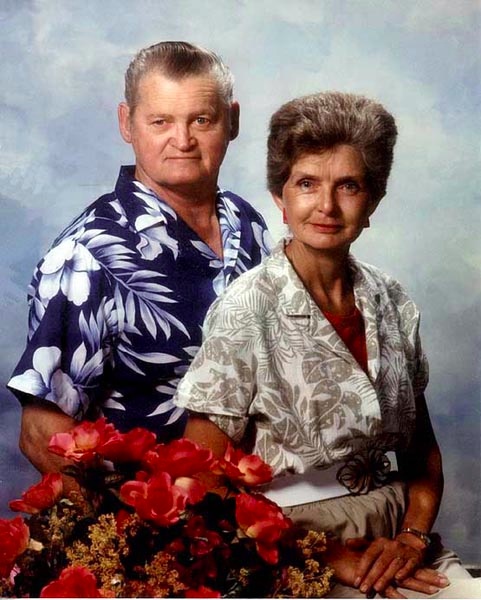

I rarely made it back to the Pacific Northwest after that, work and my family kept me away. If I had any doubts about my chosen life, it was that it prevented me from seeing those people I grew up with. Every few years I’d get back for a too-brief visit, like this one just thirteen years ago.

She was looking good! I was back a few years later, and got together with all the surviving members of the family.

Jim has since died, as has Bebe the dog. Mom checked herself into the hospital earlier this week, not feeling at all well. Yesterday, she wanted most of all to just go home, to the house she’s been living in for the last 40 or so years. She told the doctor she wanted to see her dog again.

She died quietly, peacefully in the hospital. She didn’t get to go home or see her dog.

The strobe flashes one more time, and I remember my earliest specific memory of my mother. We were living in an apartment in Kent, which places this, near as I can guess, around 1960. I was three, Mom was twenty. She’d bought a little toy microscope at the Goodwill store, and was showing me how to use it. It had a mirror in the base, and while we never got a memorable image on that thing, we had a good time moving around trying to find the best beam of sunlight to focus on whatever specimen we had. She told me we had to chase the light and catch it.

Good advice, Mom. Chase that light. Thank you for everything.