On the absurdity of g

Pharyngula 2016-04-12

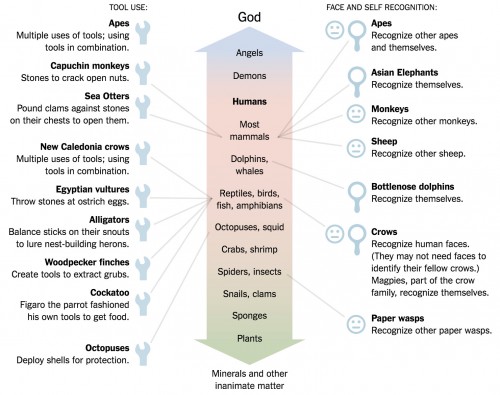

Since we’ve been talking about the biological basis of intelligence lately, this is appropriate Frans de Waal writes about animal intelligence. His whole point is that this thing we call “intelligence” is multi-dimensional and complex, and that other animals share properties of the brain with us. There are lots of ways an organism can be smart!

But think about it: How likely is it that the immense richness of nature fits on a single dimension? Isn’t it more likely that each animal has its own cognition, adapted to its own senses and natural history? It makes no sense to compare our cognition with one that is distributed over eight independently moving arms, each with its own neural supply, or one that enables a flying organism to catch mobile prey by picking up the echoes of its own shrieks. Clark’s nutcrackers (members of the crow family) recall the location of thousands of seeds that they have hidden half a year before, while I can’t even remember where I parked my car a few hours ago. Anyone who knows animals can come up with a few more cognitive comparisons that are not in our favor. Instead of a ladder, we are facing an enormous plurality of cognitions with many peaks of specialization. Somewhat paradoxically, these peaks have been called “magic wells” because the more scientists learn about them, the deeper the mystery gets.

I also very much like this illustration of the scala naturae that shows all the ways intelligence doesn’t fit neatly onto a progressive ladder (the only good use of the ol’ scala anymore is in debunking it).

There isn’t even just one kind of human intelligence! Simon Singh quotes a book Joshua Foer on people with amazing memories, discussing savants. Savants exhibit extreme intellectual abilities, but they’re all different — and they demonstrate that even human intelligence isn’t unitary.

And yet, combing through the literature, one comes across a few rare cases here and there – perhaps less than a hundred in the last century – of savants with remarkable memories who appear to break the rules. What’s most striking about these individuals is that their exceptional memories – “memory without reckoning,” it’s been called – almost always coexist with profound disability. Some are musical prodigies, like Leslie Lemke, who is blind and brain damaged and couldn’t walk until he was fifteen, but can nevertheless play complicated musical pieces on the piano after hearing them just once. Some are artistic prodigies, like Alonzo Clemons, who has an IQ of 40 but can sculpt lifelike animals from memory after just a fleeting glimpse. Some have freakish mechanical skills, like James Henry Pullen, the nineteenth-century “Genius of Earlswood Asylum,” who was deaf and nearly mute, but built stunningly intricate model ships.

This illustrates one of the contradictions inherent in the idea that we can just make people super-smart. They imagine creating a race of neurotypical people who are just more extreme — who are better at engineering and science, for instance. But the whole thing about being neurotypical is that we’re in a state of a kind of balanced mediocrity…all the bits and pieces of our minds are working together in a low-stress fashion, and in a similar way to how most other people’s minds are working. You just can’t make mediocrity extreme.

There certainly are aspects of intelligence that are biological in basis. The blithe confidence that there’s just one kind of intelligence, the mythical g, flies against everything we know about the complexity of brains, human and animal. It’s the myth that allows them to think we can just make people smarter, like turning up a single dial on a big control board. But the truth is that there are hundreds of dials, all working in harmony (we wish), and that everyone is making a different melody. Crank one up, and you fracture the song. You might get something useful to society, but you won’t necessarily make someone who is happily productive.