Now here’s a tour de force for ya

Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science 2024-04-21

In social science, we’ll study some topic, then move on to the next thing. For example, Yotam and I did this project on social penumbras and political attitudes, we designed a study, collected data, analyzed the data, wrote it up, eventually it was published—the whole thing took years! and we were very happy with the results—and then we moved on. The idea is that other people will pick up the string. There were lots of little concerns, issues of measurement, causal identification, generalization, etc., and we discussed these in our paper, again hoping that these will be useful leads to further researchers.

And that’s how it often goes. Sometimes we return to old problems (for example, we wrote a paper on incumbency advantage in 1990 and followed up 18 years later), and we’re still working on R-hat, over 30 years after I first came up with the idea), but, even there, we’re typically not working with continuous focus.

The opposite approach in science is to drill down obsessively on a single phenomenon, to really pin it down. I think this is what historians do when they immerse themselves in some archive for a decade and then emerge to write the definitive book on the topic.

Here’s an example, not from history but from cognitive psychology, by Andrew Meyer and Shane Frederick:

This paper presents 59 new studies (N=72,310) which focus primarily on the “bat and ball problem.” It documents our attempts to understand the determinants of the erroneous intuition, our exploration of ways to stimulate reflection, and our discovery that the erroneous intuition often survives whatever further reflection can be induced. Our investigation helps inform conceptions of dual process models, as “system 1” processes often appear to override or corrupt “system 2” processes. Many choose to uphold their intuition, even when directly confronted with simple arithmetic that contradicts it – especially if the intuition is approximately correct.

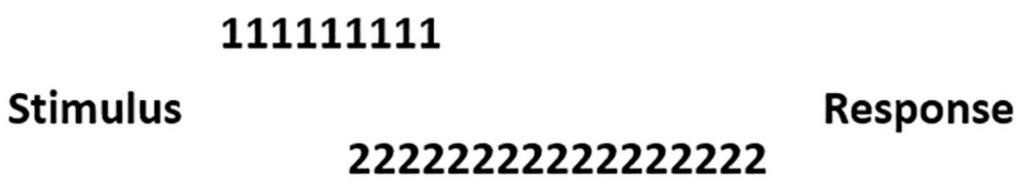

The paper contains the charming Ascii graphic reproduced above (for example, page 8 here). I love Ascii graphics! Regarding the paper, Frederick writes:

One thing I’m proud of is summarizing 59 studies in just 9 pages. Another thing I like, and you’ll probably like, is that when sample sizes get large enough (and we have some pretty large ones), psychology starts to look like physics.

What really impresses me about the paper is not the sample size but the obsessiveness of the project. And I mean that in a good way.