Book Review: Socialist Escapes: Breaking Away from Ideology and Everyday Routine in Eastern Europe, 1945-1989

EUROPP 2013-09-17

During much of the Cold War, escape from countries in the East Bloc was a near impossible act. There remained, however, possibilities for other socialist escapes, particularly time away from party ideology and the mundane routines of everyday life. The essays in this volume seek to examine sites of socialist escapes, such as beaches, camp sites, and concerts, and explore the effectiveness of state efforts to engineer society through leisure. Cultural historians and sociologists will appreciate this fascinating glimpse into cultural life under state socialism, writes Eleanor Bindman.

During much of the Cold War, escape from countries in the East Bloc was a near impossible act. There remained, however, possibilities for other socialist escapes, particularly time away from party ideology and the mundane routines of everyday life. The essays in this volume seek to examine sites of socialist escapes, such as beaches, camp sites, and concerts, and explore the effectiveness of state efforts to engineer society through leisure. Cultural historians and sociologists will appreciate this fascinating glimpse into cultural life under state socialism, writes Eleanor Bindman.

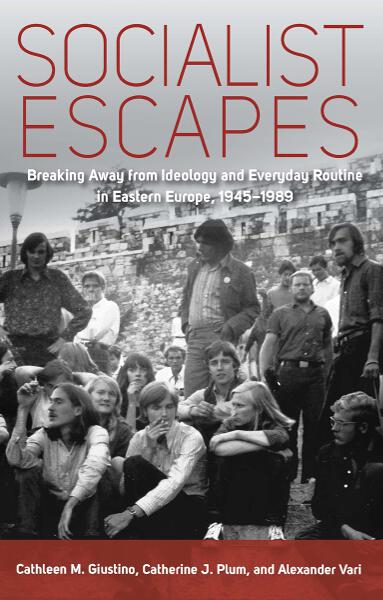

Socialist Escapes: Breaking Away from Ideology and Everyday Routine in Eastern Europe, 1945-1989. Cathleen Giustino, Catherine Plum and Alexander Vari (eds.). Berghahn Books. April 2013.

Socialist Escapes: Breaking Away from Ideology and Everyday Routine in Eastern Europe, 1945-1989. Cathleen Giustino, Catherine Plum and Alexander Vari (eds.). Berghahn Books. April 2013.

Socialist Escapes is a bold and wide-ranging attempt to explore an area of everyday life under Communism in Eastern Europe which has previously received relatively little attention: namely, the ways in which people chose to spend their leisure time and the extent to which they were able to use their leisure pursuits to escape or in some way subvert the control over their everyday lives that the region’s Communist regimes tried to exert. This collection of essays covers leisure activities as diverse as children’s summer camps in East Germany, tourism in Bulgaria, sport in Romania, and night life in Hungary, and shows how such activities provided both relief from the mundane nature of life under Communism and a form of what Alexander Vari describes in his introduction to the volume as a ‘softer form of dissent’ against the regimes in place in post-war Eastern Europe.

As several of the contributors point out, control over citizens’ everyday lives – including the opportunities available to them for relaxation and enjoyment – was motivated by both ideological and political imperatives, with state-sponsored ‘productive’ leisure opportunities seen as a way to fulfil the dual objective of securing political legitimacy and providing a reward for labour. In her chapter on socialist summer camps for children in East Germany, Catherine Plum points out that such camps were designed to provide a regimented space in which those attending would be exposed to even more political propaganda than they had already experienced at their schools and in the Pioneer troops to which most belonged. Vari’s chapter on night life in Budapest explores how sites such as the city’s Ifipark (Youth Park) entertainment complex, which was open from 1961 to 1984 and run by the Communist Youth Alliance, were intended to provide controlled, ‘civilised’ environments in which young people could socialise, provided they conformed to the dress code which stipulated ‘short hair, neckties and a suit’ for boys and ‘decent skirts’ for girls.

The fall of the Berlin Wall, November 1989. Credit: Gavin Stewart CC BY 2.0

At first glance, Tibor Fischer’s description of socialism as ‘not the sort of tyranny you’d want to invite to a party,’ which Vari quotes in his introduction, seems apt. Yet the various contributors to this volume show how gradually these state-sponsored sites were used for the expression of non-conformist behaviour as the legitimacy of the regimes in place began to be eroded and people gained greater awareness of music and fashion that was popular in the West. By the early 1980s, East German youth camps had moved away from providing explicitly political activities towards playing English-language pop music at their discos and providing opportunities to meet West German youth and question them about their lives. In Budapest by the late 1970s and early 1980s the Ifipark was hosting hard rock concerts and the previously subversive wearing of jeans had become more accepted, while punks who were denied entry to the complex gathered in large numbers outside the gates and underground clubs mushroomed. As Catherine Giustino points out in the volume’s conclusion, these and other events indicated that significant cultural and social change did take place in everyday life after Krushchev’s thaw began in 1956, but this process was gradual rather than dramatic. In addition, socialist regimes in the Eastern Bloc had to strike a balance between providing night life and tourist attractions which would bring Western visitors and their much-needed hard currency to the region, while trying (and frequently failing) to prevent their own citizens being exposed to Western ideas and tastes. Over time, awareness of higher living standards in the West created demand amongst populations in Eastern Europe which the various regimes were unable to meet.

This volume uses a mixture of interviews with members of the public who engaged in the different types of leisure activity of interest to its contributors, archival resources and newspaper reports to provide a fascinating glimpse of various aspects of leisure and cultural life under state socialism in Eastern Europe which will be of interest to sociologists, cultural historians and students of both disciplines. The authors indicate the subtle and at times unlikely ways in which a system presumed to exercise total control over the lives of its systems could in fact be subverted at a grassroots level and thus paint a convincing picture of how the presumed monotony of everyday life under socialism was in fact anything but.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1ea4bSu

_________________________________

Eleanor Bindman Eleanor Bindman is a third-year PhD researcher in Politics at the University of Glasgow. Her research focuses on the EU’s human rights policy in relation to Russia, with other research interests including contemporary Russian politics, international relations and social policy. She previously studied Russian language, history and politics at the universities of Edinburgh and London and in 2010 worked as an intern for the Commissioner for Human Rights at the Council of Europe in Strasbourg. Prior to starting her PhD she worked as a research assistant for Human Rights Watch in Moscow and has also worked as a freelance translator for several years. Read more reviews by Eleanor.

Eleanor Bindman Eleanor Bindman is a third-year PhD researcher in Politics at the University of Glasgow. Her research focuses on the EU’s human rights policy in relation to Russia, with other research interests including contemporary Russian politics, international relations and social policy. She previously studied Russian language, history and politics at the universities of Edinburgh and London and in 2010 worked as an intern for the Commissioner for Human Rights at the Council of Europe in Strasbourg. Prior to starting her PhD she worked as a research assistant for Human Rights Watch in Moscow and has also worked as a freelance translator for several years. Read more reviews by Eleanor.

Related posts:

- Book Review: The Politics of Art in Modern Egypt: Aesthetics, Ideology and Nation Building

- Book Review: Human rights needs to be recognised as more than a buzz phrase, it is grounded in our everyday experiences

- Book Review: Our Racist Heart? An Exploration of Unconscious Prejudice in Everyday Life