Habemus Erratum: How Twitter Could Help Fight the Spread of Errors

technosociology 2013-03-14

A common complaint about online platforms such as Twitter and Facebook is that errors and rumors propagate too easily. For example, Andy Carvin’s recent book A Distant Witness has striking examples from the Arab uprisings of 2011–and documents his extensive efforts to counter and quelch them. It’s certainly important for some people to actively play the role of fact-checkers but a lot of the errors are honest mistakes made by a wide variety of people. I’ve written previously on comparing structural sources of error in traditional journalism with social media environments and there is a lot to be done at the institutional and individual level. But that is never the whole picture. We should also be thinking about the role of design of online platforms on how to counter, correct and halt the spread of errors.

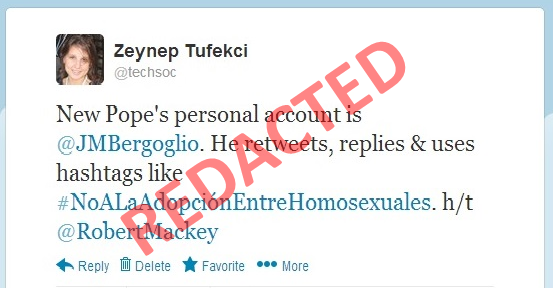

Of course, the way errors propagate (or don’t) also depends on the composition of your social network—as I discovered within seconds after I sent out an erroneous piece of information on Twitter about the new Pope:

I had corrections pouring in almost within seconds. To be honest, it was a careless mistake. I apologize. I was correcting proofs of a peer-reviewed article of mine using a restricted version of Adobe–and I was frustrated. I turned to the excellent “The Lede” section of the New York Times to see how they were covering the announcement of the new Pope. The event seemed like a clear example of a “Media Event” –spectacles performed to be consumed by (often global) publics such as the Olympics, royal weddings, etc. which were first explored by the classic book by Dayan & Katz.

The naming of the Pope had clearly become a global media event but now with the addition of social media to its shaping—most everyone on my Twitter timeline (ranging from Egyptian revolutionaries to Turkish students to academics to journalists) was either talking about it or complaining about why others were talking about it. Almost all worldwide trending topics were about the papal transition. The new Pope-to-be had captivated that crucial, scarce resource: attention.

And then the Pope was announced and immediately, The Lede posted that there was a personal twitter account of the new Pope. The new Pope’s speech had just mentioned new communication technologies. Robert Mackey, who runs the Lede, is a journalist experienced in using social media and has always been very keen on figuring out false information out there so I started with trusting the information. It all seemed plausible in my less-than-fully careful state. I glanced over to the alleged account, translated a few of the tweets and put out the aforementioned erroneous tweet and decided that it was about time I returned to wrestling with Adobe.

Of course, as you can see above, my tweeps jumped to correct my careless mistake. I think I had dozens of people within two minutes. (I take this as a compliment to my own efforts to engage with careful, sharp people on social media!) In fact, I have seen this happen many times—Twitter may make it easy for errors to propagate but it also makes the corrections easy to propagate. The process of correction can often be much faster than traditional journalism where major errors –reporting on Iraq’s non-existent stocks of Weapons of Mass Destruction—persist for years and only be corrected after it’s all too late.

Of course, I quickly corrected my error as did The Lede and as did Robert Mackey on Twitter. The problem, remained, though, with the original tweet. It was still there and I started pondering what to do about it.

Here are my options as Twitter design currently affords:

1- I can delete the erroneous tweet. That would also “disappear” the retweets but it would not alert the retweeters that I had deleted it. How would they know something in their past timeline was now gone? It would be an unknown unknown to them—they wouldn’t know that they don’t know I corrected it. It would also disappear the record of my error—not a big deal in my case but there is reason to think that keeping a record of errors is healthier for journalism.

2- I can keep issuing corrections in the hopes that everyone who retweeted my original tweet will see it. Odds of success? My experiments say very little. People dip in and out of streams so corrections don’t always get seen.

3-I can “mention” everyone who retweeted my erroneous tweet—poke them in the eye with the correction, so to speak. I can also urge them to “retweet” my correction so that their network who saw the error in their own timeline can also see the correction.

However, even as I was thinking all of this (and discussing it on Twitter) more and more people were retweeting my original tweet. Not only were tweeps not seeing my correction, they were somehow seeing my error, untouched, and not noticing the many, many comments under it correcting it.

Here’s why it’s useful to think about how design and “affordances” –what design allows, makes easy, makes hard, facilitates and inhibits—influence our social processes. Twitter makes it easy for errors to propagate and also makes it easy for people to challenge errors. But it does not make it easy to correct honest mistakes one makes and wishes to correct.

What would such an affordance—a new feature—look like?

Here’s one suggestion.

First, it has to make sure the “error” is clearly marked as error–which is why Alexis Madrigal put a huge “fake” or “real” or “unverified” in bold colors in of photos he was verifying or debunking during Hurricane Sandy: just the existence of the photo in a high-profile outlet can help propagate the error even if the text says the photo is fake unless the world “fake” and the photo are inextricably intertwined:

Second, it has to be a push mechanism. Pushing content to people is tricky business but there is no iron law that it cannot be done—but it is certainly open to abuse. Issues of consent certainly matter and I think it is perfectly justified for Twitter to assume following someone PLUS retweeting their content as implied consent to the occasional, simple correction by the originator.

Third, it has to be straightforward and limited so it does not become a way to push spam or other unwanted content or to repush a message.

So, I suggest Twitter lets me push the same tweet but now visibly slapped with one of three simple labels on it: “ERROR”, “RETRACTED” or “SORRY” nothing more. There should be a limit to how often you can do this (Only one per hour?). It should go to every person who retweeted the original message based on the assumption that if they are interested enough to retweet, they should be interested enough in the correction.

So, I want something like this to be shown to everyone who retweeted the original message, as well as this appearing on the original tweet itself:

Why not? Twitter already pushes promoted content, and it has made many design changes over the years. It has incorporated many innovations that were pioneered by users into its platform–that’s how we got the native retweet in the first place. This one could significantly help Twitter’s reliability as a platform—and given its key role in breaking news and a place for citizen journalism, it would be a healthy move.