#Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood Teaches a Lesson in Elections in the Age of Twitter and Google Spreadsheets

technosociology 2012-06-24

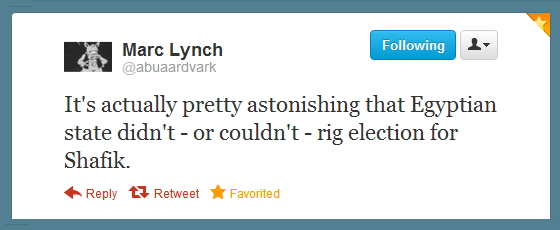

Shortly after the announcement that Mohamed Morsi had won Egypt’s presidential elections, political scientist Marc Lynch asks a very good question:

Indeed, ex-president Hosni Mobarak had handily “won” the “elections” in 1987, 1993, 1999 and 2005, going to a mere 88% of the vote from a more proper 97% in 1987. The same apparatus that “won” Mobarak’s previous elections was in charge of most of the electoral machinery of the 2012 elections. It’s true that a major uprising|revolution|coup|spring [pick the term that least offends you] happened in 2011, but attempts at election fixing post-uprising would certainly not be the first or the last time.

There may be many reasons for the apparent results, and it’s certainly possible that the Ancien Régime [or Felool as many Egyptians refer to them] just didn’t have it in them to fight this one. Maybe they became late-believers in democracy (Though admittedly a weak hypothesis, as old-regime courts first disqualified the front-runners, then nullified the elected parliament, and finally greatly clipped the powers of the presidency in favor of the military council). Or, as some believe, maybe the military cut a deal with the Muslim Brotherhood.

Whatever else went into the apparent results, I’d like to suggest that the Muslim Brotherhood (or Ikhwan as Egyptians refer to them) made it harder for the election to be stolen because they combined a superior ground game with active and sophisticated online presence to control the narrative and force a level of transparency. (In other words, they forced it such that if the elections were going to be stolen, it was going to be “in-your-face” stolen which is a very different method with greatly different political implications than “under-the-rug” stolen).

Here’s how.

First, Muslim Brotherhood has a fairly active presence online, and especially in Twitter (although only their English feed is interactive at the moment). Throughout the election night, they kept tweeting out updated results:

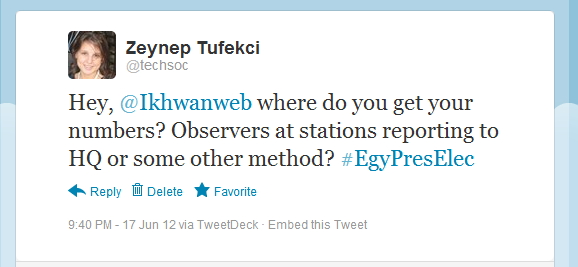

I was curious about where they got their numbers so I asked them:

About 10 minutes later, I had a reply that they had people at polling stations who updated them regularly. [Full disclosure: I do personally know at least one of the young woman who runs their English feed; in fact, most of my contacts with Muslim Brotherhood have been with young women as they happen to be quite active on their new media operations]. Other people I knew confirmed that MB had people on the ground at polling stations and were feeding results to the central headquarters as they became available.

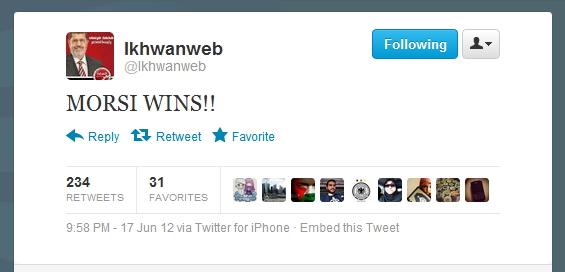

This went on all night. As soon as results from all governorates (the official legal ruling structure of Egypt) were in, Muslim Brotherhood’s twitter feed, @Ikhanweb cheerily announced:

Plus, Muslim Brotherhood quickly put up a Google spreadsheet that had results from all governorates clearly showed an almost 4 percent victory for their candidade, Mohamed Morsi. I watched many journalists use this spreadsheet as a resource; in fact, Evan Chill quickly translated it to English, making it even more useful to a broader audience.

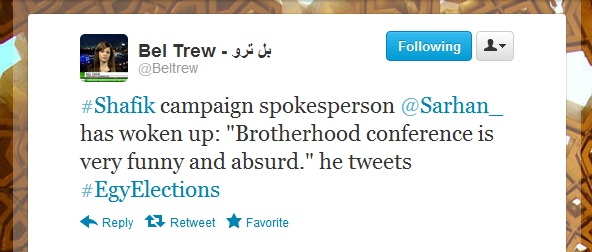

Meanwhile, Twitter feed for Shafiq’s official spokesperson was fairly quite. All the journalist –and pretty much everyone I know in Egypt– was up into the night and following the results, and the narrative was clearly emerging both on Twitter and in international media that MB had won the vote–but the question remained if they would win the election.

When Shafiq camp finally “woke up”, they had a relatively feeble response, made basic errors and invited ridicule rather than authority.

Egypt went to night that morning with the feeling that MB had won the count, but with great uncertainty what the official results would be. (Keep in mind that this is the very first competitive election for presidency *ever* in Egypt.).

What happened next week was a true soap opera. It took a week for the Egyptian official election commission (PEC) to certify the results. The delay made many people fear that the vote would be rigged. Muslim Brotherhood took to Tahrir to demonstrate that they were not going to give up easily. Many speculated that MB and the SCAF, Egypt’s military council were in negotiations.

The final announcement of the results was almost comical if it had not been such a disservice to that country’s potential. After keeping the country waiting for a week, the head of the PEC showed up 40 minutes late and instead of announcing the results, gave an hour long rambling speech detailing how they dealt with various complaints while Egypt held its breath and world news organizations broadcast this live.

My Egyptian friends first reacted by making fun of this display of old guard authority, but were soon quite angry that this was the image that their country was broadcasting to the world–a country run by the old guard which was not about to give up its monopoly to speak as long as they wanted, no matter the occasion or the question. Many of us took this rambling speech with clear jabs at Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood as a sign that the vote was going to be rigged and the winner to be announced was the establishment candidate, an ex-premier and a general.

And, yet. And, yet. When it came time for numbers to be added and presidents to be named, head of the PEC, Farouk Sultan, looked up from his papers and a bunch of numbers rolled of his tongue almost as an afterthought. And those numbers were within 0.01% of the Muslim Brotherhood tally on that Google Spreadsheet.

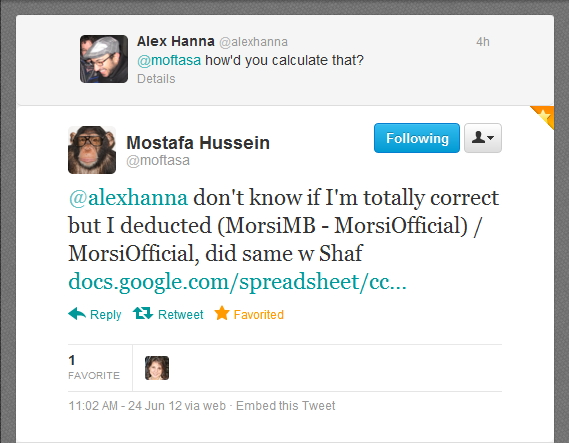

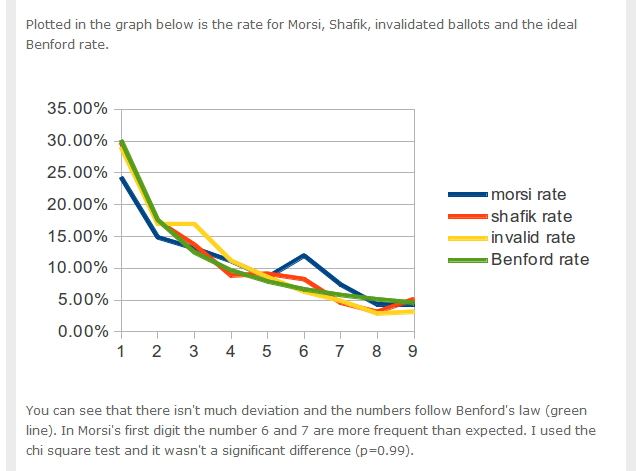

In fact, revolutionaries and dissidents were quick to run the numbers and compare the official numbers of the PEC with MB numbers. (Heck, not only that, Moftasa Hussein had already applied the Benford’s test, which can be used to detect manual manipulation of numbers which should be more randomly distributed, to the unofficial numbers).

How influential was the fact that Ikhwan had so many verifiable numbers out in the open for the last week in convincing the old-regime apparatus to stick to the numbers as they were? We’ll likely never know. Perhaps it is best to assume that they would have done so anyway. However, it is hard to deny that had they been tempted to fix the numbers, that Google spreadsheet would stare at them at every turn. And the narrative laid by Ikhwan’s online and offline operation would be hard to surmount.

There are certainly huge problems with the electoral process in Egypt (here’s a bunch of them as outlined by Marc Lynch who has taken to calling the current system “Calvinball” ). Egypt certainly has a ways to go, and hopefully for the better. Many will be watching to see whether Ikhwan can translate its new found position to charter Egypt in a more democratic and humane direction while respecting the rights of minorities and secular groups.

We have, however, just witnessed that they certainly know how to use on-the-ground electoral machinery with a sophisticated and 21st century approach to controlling the media narrative.