The Syrian Uprising will be Live-Streamed: Youtube & The Surveillance Revolution

technosociology 2012-03-08

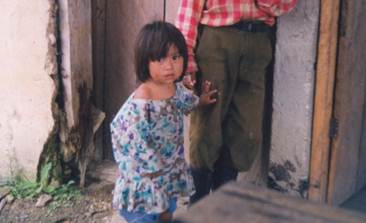

I met this girl in a little village tucked away in the gorgeous but harsh highlands of Chiapas, Mexico:

After the Zapatistas burst into the scene in the 2000s 1990s with their uprising, there was a lot of discussion about their use of the Internet–and I was quite curious about that aspect*. I was a graduate student and it was quite easy to get to southern Mexico, especially if one took a cheap flight to Cancún and took the first bus out of that overbuilt heap of cement. There’s probably no harm in naming the particular village at this point, but the name hardly matters as it was a fairly typical Zapatista community, nestled between beautiful mountains and high enough to be in the clouds which look so delicate from afar but chill you to the bone when you are in their midst.Let’s just say it was this village:

I visited Chiapas multiple times over the years and I’ve always been careful about taking pictures of people as people’s attitudes to cameras vary from region to region, or even village to village. They are often wary. On this occasion, though, it was this girl’s mother who insisted I take her picture. Puzzled, I tried to inquire why. Conversation was difficult as the women in these remote villages spoke very little Spanish, not to say anything about my linguistic inadequacies in Spanish. With the help of children who seemed to switch easily between Mayan languages of Tzoltil, Tzeltal, Tojolobal (as that particular area was at multilingual crossroads) and Spanish, she explained to me that she wanted for there to exist pictures of her children who grew before her eyes. It wasn’t just that there was no running water or electricity in this village. There were also no cameras. Time was reduced to its essence: ephemeral and passing. I did quickly ponder the ethics of the situation, and my own role in introducing new technologies, but quickly decided that I was in no position for any pretentious pondering of the “prime directive.” She wanted pictures of her children. I clicked on the shutter.

Fast forward just a little more than a decade, and we it seems we have cameras everywhere. Everywhere. Youtube’s “news director” Olivia Ma once told me that within about an hour of something of some importance happening anywhere in the world, Youtube has video of it uploaded. It is striking enough that Youtube has a news director. It’s stunning that videos of almost all events appear on Youtube within such a short time. In fact, correctly put, it would not be incorrect to say that Youtube is probably the biggest news site in the world–and that fact is often overlooked because there is also so much else on the site. Sometimes, it can take a while for a significant video to be discovered and no doubt that some never are beyond a small audience but there is almost always something, however shaky and grainy. This is nothing short of a revolution in surveillance capacity of citizenry.

One may wish that stoning death of Yazidi Kurdish young girl Du’a Khalil Aswad in 2007 was never discovered on Youtube, but that seems so trivial compared to wishing that she was never killed in such a cruel, brutal fashion. She was, though, for the alleged crime of seeing a boy of a different faith. She was murdered somewhere early in April 2007 and the video of her awful death started circulating widely later that month. A few weeks after her killing, and a few months after the video was discovered and eventually made headlines around the world, a series of bombings shook Yazidi villages near Mosul, resulting in about 800 deaths and more than 1,500 injured—making it the single biggest episode of mass killing in an act of political violence since September 11, 2001. While the culprits were never discovered, most observers traced the events to the tensions that began with the video of her death.

The fact that the event was filmed and uploaded to the Internet is quite striking, too, considering the community. The Yazidis are a mostly Kurdish speaking religious group in the Middle East who keep to themselves as much as they can. The reasons for their protectiveness is lengthy and complicated but is related to the fact that a central figure in their faith, Melek Taus is accused of being identical to the Muslim figure of Satan. Having faced much prosecution, and also having a contentious faith in a contentious region, Yazidi society is predicated upon keeping outsiders out and practices strict endogamy—no marriage with outsiders.

Du’a Khalil, just 17 years old, crossed just that line with her alleged relationship with, and rumored conversion to Islam. For that, she was dragged to the street by a few dozen men who proceeded to beat her to death as she curled up on the ground, bleeding. The shaky and grainy video, which I saw in bits over the space of a few days as I could not bear to watch in in a single sitting, shows at least *three*other people recording her stoning with cell phones. It is quite stunning to think—not only are they killing her –this secretive, closed society which managed to survive for thousands of years by being so guarded and cautious— her killers felt like they should film this. Not one of them but at least four. And, more, upload it to the Internet.

Below, I’ve included the same stills from her death that Wikipedia has; the video is harrowing.

I’ve been thinking about that incident as I’m recently thinking a lot about what it means to have so much video of horrific death and destruction out of Syria. Indeed, as one journalist I spoke with put it, we are literally watching a war on civilians being live-streamed. Despite all efforts by the Syrian regime, it is quite clear that this is not censorable or stoppable. The combination of cheap and small satellite modems and a fairly dispersed uprising has meant that there is truly no real way for the government to shut this down. The Syrian uprising will be live-streamed.

I have more questions than answers. What does it mean that everything –including the most trivial but especially the non-trivial– has such a great chance of being available worldwide? Starting with the printing press, the threshold for the ability to publish has been getting lower, and the potential reach of publications has been getting bigger. We are now at the level of the person, publishing at the level of the world. The publishing revolution is almost complete.

Does this level of documentation make it more likely that the international community will be compelled to react to atrocities–which will likely come with higher and higher levels of visibility? Or will this, too, become just background noise, similar to famines or disease in Africa have become for most of the world (except the victims, of course)? Does the level of documentation and surveillance –and thus, evidence– make it harder to establish processes like the Truth and Reconciliation efforts in places ranging from South Africa to Guatemala? Will this amount of documentation of atrocities make divisions even more likely and pernicious–as the ability to forgive often needs some level of forgetting? And the Internet, it seems, does not forget. Will this all make regime bureaucrats more likely to defect—as “I was just pushing paper and had no idea all this was going on” has become an even weaker defense? Or will they cling to power to the very end as much as they can, knowing their victims and survivors have much evidence as well as awful reminders of their crimes?

I don’t have the answers but I’m quite convinced that we’ve entered an irreversible point in terms of documentation of our lives, including death and destruction—not just baby pictures and trips, parties and graduations but also shelling of towns and killing of children. There is no going back. And tools matter. Just as wars with nuclear weapons are different than wars with bows and arrows, a world with cell-phone cameras in every other hand is different than a world which depended on traditional journalists and mass media gate-keepers for its news.

I want to emphasize that I am not making the argument that we, as humans, are drastically different in terms of our urge to document. In fact, I find such approaches to technology to be without support. Most of the time, the remarkable changes from technology come not because people suddenly start having new and unprecedented urges but rather because people continue to practice their mundane and human urges—but under drastically different conditions. The difference is not in human nature but in the socio-technical architecture. So, it seems, with our urge to capture out lies. The speed which we have taken this up clearly means we must have always had the itch to document, to surveill, and to display and share. But now we can scratch and scratch and scratch–and share on a global scale with a click.

I left my camera with that mother in Chiapas and have never gone back to that exact village to find out what has happened. It’s quite possible that not much has changed. Women are probably still painstakingly grinding the corn by hand, and children probably still go out at dawn to collect firewood from the dwindling surrounding forest for the stone tortilla ovens. There probably still isn’t a doctor within a reasonable walking distance of a day or so.

I am quite sure, however, that there would be at least a few cell phones with cameras in that village–as there are now in villages around the world, from Africa to rural India. And as more and more of those cell phones come with basic audio-visual capabilities, the surveillance revolution is here to stay. And I hope that little girl –probably a teenager now– is doing well, and I hope her mother has a few pictures of her as a toddler and as a young child to remind her of the days gone by. But I mostly hope that their future is even better.

* PS. The extraordinary thing about the Zapatistas and the Internet was not that the Zapatistas were that much different (or “postmodern” as commonly claimed)–in fact, they were a quite ordinary Latin American peasant uprisings in many respects. However, their insurrection took place in a world where the Internet was emerging as a powerful tool for political communication–and that did make a big difference. That topic deserves a post of its own so I’ll leave it there.

*** PPS. The date typo confused a few people. I was not there in the early days of the uprising –followed it closely, but from a distance–. Rather, I traveled there later multiple times while the unrest was ongoing.

<Soundtrack for this post was Joni Mitchell, “The Circle Game.” >