Too Many Messages and Only One Facebook Page: April 6th Movement in Post-Mubarak Egypt

technosociology 2012-03-08

Guest post by Susannah Vila

This post draws from over 30 in-depth, semi structured interviews conducted with coordinators of and participants in the Egyptian revolution between March and August 2011.

By late July, Egyptian protesters in Cairo had been camped out in Tahrir Square for nearly 3 weeks. Though the mood was jovial, it was clear that residents of the square were considering an approaching end game.

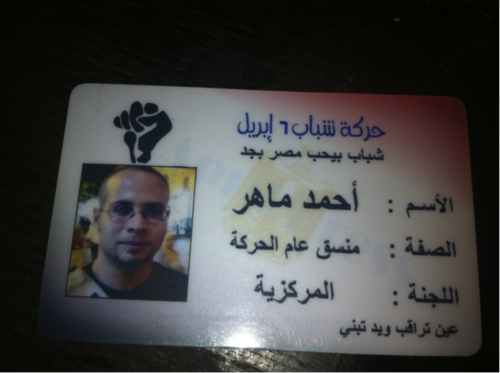

During this wind-down of the 3 week sit-in, I met Ahmed Maher from the April 6th Youth Movement a few blocks from Tahrir at a coffee shop. April 6 (hereafter A6Y) is perhaps the most well-known network of young people coordinating actions during the years before January 25th. In recent months a spate of new, wired revolutionary youth movements, many of which were formed by Egyptians that were politically activated by the winter’s uprising, have also emerged.

Maher still has a day job, and does all of his April 6 related work after sunset. It was nearly midnight when we got together. He said a few hellos – nearly half of the customers seemed to know him –sat down, and rushed into an account of A6Y’s recent growth.

“There is no split,” he assured me, referring to accounts in the Egyptian and international press of infighting and divisions among A6Y members. This affirmation was partly true. A6Y did indeed turn out to be much more intact than I had expected. It still, however, struggled to communicate its goals and messages to the more tech-savvy revolutionaries that were sitting in mere blocks away.

The fact that it wasn’t hard to find someone in Tahrir who would express disillusionment with A6Y is indicative of the larger challenge that he and colleagues face today: after the political sphere is broken open by uprising, how do you maintain and build upon support among the highly-wired crowd while simultaneously recruiting offline Egyptians? A6Y’s struggle to address this question has left it, as FP’s Marc Lynch put it last week, one of many wired revolutionary movements currently “floundering” and unable to connect either with one another or with the general public. But, as my discussions with Maher and others would make clear, this is not for lack of trying.

Adapting the Organizational Structure for Offline Outreach

In the years before the uprising of January 25th, fear of state repression made offline organizing a difficult feat. The online space – from blogs and YouTube to Facebook- created an alternative public sphere wherein a movement could more covertly engage with, and be discovered by, new supporters. As one Egyptian activist put it, “we couldn’t talk like this on the street…we had to do it online.”

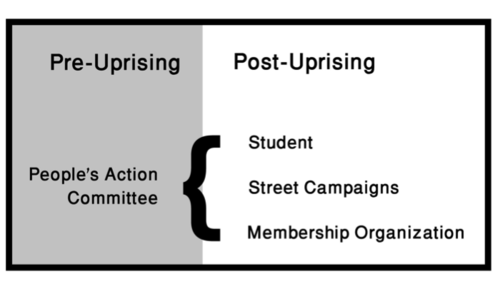

The transformation of Egyptian political culture after Mubarak’s ouster has made it easier to engage and mobilize citizens in the offline space. Taking advantage of its newfound ability to organize freely on the street, A6Y has restructured to allocate more resources to recruitment efforts. Grabbing a pen from the table next to us, Maher drew me a diagram of the 4 committees through which April 6 allocated responsibility before the uprising and then a diagram of the 6 that it consists of today.

Before January 25th , A6Y was divided into a media, political, finance and people’s action committee. Since the work of the people’s action committee – recruiting and mobilizing new members – can now be done publicly and offline, its mandate expanded and its management structure was split it into three committees with separate leadership.

The purpose of expanding and refining its recruitment strategy is to gain further leverage and power in the political sphere. The more loyal, reliable and organized the movement’s membership is, this thinking goes, the more effectively it will be able to hold government accountable.Rather than simply joining a Facebook group, a member must now pay monthly dues and carry an A6Y identification card.

By raising the barrier to entry, Maher hopes to enhance the value of membership as a political currency. “Do we want to be like the Muslim Brotherhood?” he said. “Ask us in 80 years – that’s how long they have had,” referring to the brotherhood’s success in creating (while it was banned from politics) a civil society organization that draws political clout from the loyalty and breadth of its membership.

Building Political Support by Addressing Social Issues

A few days after my meeting with Maher, I spoke with Wael Mustafa (named changed to preserve anonymity), the leader of the street campaigns committee that acts at the center for A6Y’s offline efforts.He was quick to stress that online social networks are not a large part of his day-to-day work.

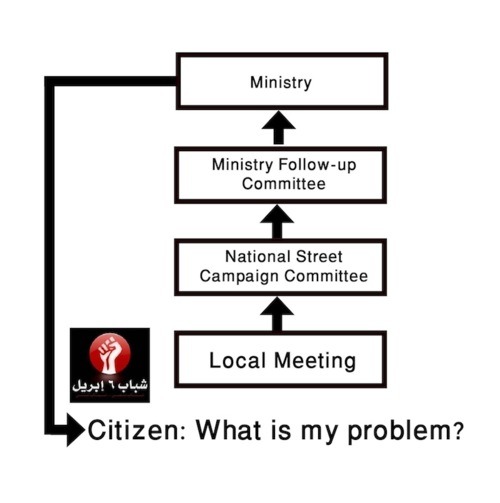

We go to different neighborhoods and ask people what their problem is – in one area [for example] there is a huge sewage problem, we take in that information, and take it to the [appropriate government] ministry,” he said of his most recent effort, called the “What’s Your Problem?” campaign.

April 6 hopes to use campaigns like this one to grow into an organization that better connects Egyptians with government –lobbying the latter to do the bidding of the former. The fate of the “What’s Your Problem?” campaign may be an important metric for A6Y’s larger success and, with this in mind, Mustafa told me, they had just decided to create a new committee tasked exclusively with interfacing between citizens and appropriate government ministries. They called it, fittingly, the “ministry follow-up committee.”

April 6th Leadership Still Relies on Facebook to Share Information

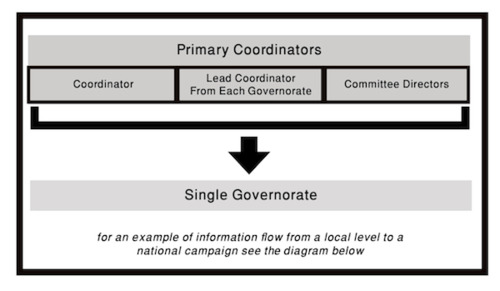

Mustafa, as head of a committee, and Maher, as the Coordinator, make up 2 of 25 people who sit at the top of the organization’s hierarchy. A leader in any given governorate spends the day talking to people in his community. He has conversations in the street, on the phone, and at daily local meetings. Then, at the end of the day, he goes to “the kitchen—the name given to the private Facebook group that primary coordinators like Mustafa and Maher have been using since before the uprising.

The kitchen is indicative of a formal hierarchy that previously existed but that has been solidified since February. It is called that because, as Maher told me, “it’s where we are cooking up our decisions.” After deciding on next steps in this online space, primary coordinators channel their decisions back down to localities through the same combination of face-to-face conversation, mobile phones and online media.

Too Many Messages and Only One Facebook Page

A6Y continues to use Facebook and Twitter as it did before the revolution: for both private, group decision-making and to curate and broadcast political news. This doesn’t seem to leave much space to disseminate information about offline activities like the “What’s Your Problem” campaign. For a movement attempting to recruit, their ability to publicize and promote their successful ventures is perhaps still insufficient.

The most dedicated revolutionaries, many of which were not active before the January uprising, know little about A6Y’s efforts at offline expansion. After my initial coffee with Maher, I met up with a member of Egypt’s new “Twitterati” activist crowd. I told her everything that Mustafa and Maher described to me. It was all news to her – and to most others I spoke to in the vicinity.

At the same time, the general public has also lost patience with protesters—including A6Y. As one Tahrir protester(who has nothing to do with April 6) told me “we’ve lost the street because our messaging is wrong, and I attribute that to a lack of a clear roadmap” for the future. Maher agreed, saying: “people are concerned about their salaries and they want us to stop protesting.”

This is compounded by the fact that their main communication tool from before the revolution, Facebook, is not conducive to the more complex methods for information broadcasting that’s required of the organization that it is trying to become. Social media is more useful for disseminating one message – we are fed up and want Mubarak out –to as many people as possible than for targeting different messages to different audiences. Ideally, A6Y would have a Facebook page intended for Tahrir Square types, and one meant for the wider, more reluctant segment of the population that joined the site more recently. (This, of course, is just one aspect of a communications effort that must target the still offline majority).

What’s Next?

“The Egyptian revolution is unique. In every other one, the person who caused it goes into government right after. We haven’t done that in Egypt,” said Maher. Indeed, from Otpor to the Orange Revolution, this is the first 21st century movement that has opted to remain a lobbying coalition rather than entering politics.

That not much has changed in Egypt in terms of who wields political power underscores the importance of A6Y’s decision to take on this role. But their expansion holds just as much peril as promise. It is hard enough for a movement to maintain support among an increasingly frustrated citizenry after a political uprising. By formalizing membership and shifting resources towards recruiting the formerly apolitical, A6Y runs the risk of deserting its base of support.

The challenges that the April 6 Youth Movement face today raise bigger questions about lessons learned for revolutionaries after uprisings. How can a movement that largely began on Facebook take organizing offline while also engaging with the younger, more wired activists, who formerly served as an important segment of its base, and are now less likely to know what its goals, plans and activities are – let alone support it?