Clever Pleading Can’t Save Koss’s Patents from Issue Preclusion Invalidity

Patent – Patently-O 2024-07-26

by Dennis Crouch

Koss Corporation v. Bose Corporation, 22-2090 (Fed. Cir. July 19, 2024)

In its final written decisions, the PTAB found a number of Koss patent claims invalid and Koss appealed to the Federal Circuit. In the end, though the appellate panel found the appeals moot because all the claims had been invalidated in parallel district court litigation. Although the prior litigation involved a different party (Plantronics), Bose was able to take advantage of that invalidation decision under the doctrine of non-mutual collateral estoppel established by the Supreme Court in Blonder-Tongue Lab’ys, Inc. v. Univ. of Ill. Found., 402 U.S. 313 (1971).

Koss attempted a clever pleading trick of filing an amended complaint and then dismissing the case – arguing that rendered the invalidity decision on the prior complaint non-final. But, the Federal Circuit rejected that scheme and instead applied issue preclusion to hold that the claims are fully and finally invalid.

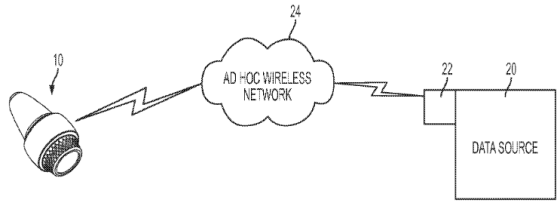

The patents at issue in this case were U.S. Patent Nos. 10,368,155 (‘155 patent), 10,469,934 (‘934 patent), and 10,206,025 (‘025 patent), all assigned to Koss. These patents relate to wireless earphone technology using Bluetooth.

Background on the Law of Non-Mutual Collateral Estoppel: Under the doctrine of collateral estoppel, also known as issue preclusion, a final judgment on the merits of a legal or factual issue, such as patent invalidity, precludes relitigation of that issue in a subsequent case between the same parties or their privies. Blonder-Tongue extended the application of collateral estoppel to cases involving different defendants. This means that once a patent claim has been found invalid in a prior case, the patent owner is estopped from asserting that claim against any other party in future litigation, even if the subsequent defendant was not a party to the original case. Earlier cases, especially throughout the 1800s, each defendant was forced to separately prove a patent was invalid — leading to situations where patents might be enforced in New York, but invalid in Illionois. Thus, the doctrine of non-mutual collateral estoppel in this context operates to promote judicial efficiency, to avoid inconsistent judgments, and to protect accused infringers from the burden of relitigating issues that have already been fully and fairly adjudicated.

While the doctrine of non-mutual collateral estoppel is an incredibly powerful defense tool in patent litigation, it is important to note that its application is not automatic or absolute. Courts have recognized that the doctrine should be applied with flexibility and consideration of the equities involved in each case. The Supreme Court in Blonder-Tongue acknowledged that there may be instances where it would be inappropriate or unfair to preclude a patent owner from relitigating the validity of a patent claim, even if that claim had been found invalid in a prior case. This caveat generally falls within the requirement that the patentee had a fair opportunity to fully litigated the particular issue, and that the issue was actually litigated and actually decided. Blonder-Tongue notes that this full-and-fair opportunity is more likely when it is the patentee who brought the original suit because “[p]resumably, he was prepared to litigate, and to litigate to the finish, against the defendant there involved.”

Although fairness continues to be an element of the doctrine, it tends to be largely ignored in patent infringement litigation. Rather, the courts tend to simply ask whether the issue was litigated and decided in a final decision. That is the approach taken by the Koss court. The court did not engage in an analysis of whether Koss had a full and fair opportunity to litigate the validity of the patents, but simply focused on the finality of the prior judgment.

The Koss Case: In July 2020, Koss filed parallel patent infringement suits against Bose and Plantronics. Bose responded by challenging venue and filing IPR petitions on all three patents. The Bose case was stayed pending the IPRs. Meanwhile, in Plantronics, venue was transferred to the Northern District of California. There, the district court granted Plantronics’s motion to dismiss, finding all claims of the asserted patents invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 101 for claiming patent-ineligible subject matter.

The district court’s invalidation ruling did not entirely dispose of the case, and Koss quickly filed a Second Amended Complaint against Plantronics, reasserting only certain claims from the ‘934 and ‘025 patents. Rather than waiting for the court to rule on Plantronics’s second motion to dismiss, Koss then voluntarily stipulated to dismissal of the case with prejudice. Importantly, Koss did not appeal the earlier invalidation of all claims or seek to have the invalidation order vacated. However, Koss argued later that its amended complaint nullified the invalidity ruling, rendering it a non-final order that could not have preclusive effect.

Back in the IPR, the PTAB issued its decision cancelling a number of Koss claims, and Koss appealed to the Federal Circuit. Bose argued that the case should be considered moot because the validity issue has already been finally decided in Plantronics. Koss balked at this argument – arguing that filing the Second Amended Complaint, which asserted only a subset of the previously invalidated claims, it effectively superseded the prior complaint and the associated invalidity judgment. Under this theory, the invalidity judgment would not be a final judgment on the merits because it was replaced by the amended pleading.

However, the Federal Circuit rejected this argument, citing Ninth Circuit precedent (treating this as a non-patent issue), the court reasoned that Koss’s decision not to reallege all the dismissed claims in the amended complaint did not affect the finality of the invalidity judgment for preclusion purposes. What mattered was Koss’s voluntary dismissal with prejudice, without seeking to vacate the invalidity judgment or preserve its appeal rights.

I’ll note that the Ninth Circuit had not directly addressed this issue, but it instead required a few logical steps. In Lacey v. Maricopa Cnty., 693 F.3d 896 (9th Cir. 2012), the Ninth Circuit held that claims in prior dismissed complaints need not be raised in amended complaints in order to appeal that dismissal. “As the Ninth Circuit explained, a rule requiring repleading is unfair to the parties and the district court.” With that ruling as a basis, the Federal Circuit reasoned that “if claims need not be repleaded to be appealable, then the order dismissing those claims is not rendered a nullity and merges into the final judgment.”

The result: Koss’s cleverness in pleading was not enough to skirt the equitable doctrine.