Single-Point-Of-Novelty Innovations and the Obvious-To-Try Analysis

Patent – Patently-O 2020-01-06

Google v. Philips (Fed. Cir. 2020)

So far there are still no precedential opinions issued in 2020, and this is the first non-precedential patent related decision.

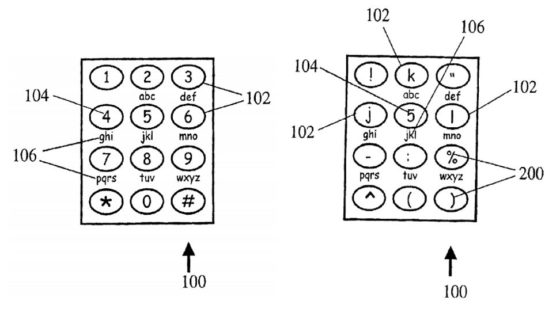

Philips’ patent RE44,913 (“text entry method”) claims a 2001 filing date. At that time, a key focus of mobile-device development was on how to facilitate typing on these small devices with relatively imprecise touchpads. The basic idea behind the invention can be seen in the two figures below. On the left is a “default” keypad with showing “primary characters.”; holding down the “5” key will then switch the display to the keypad on the rights that has more available options (“secondary characters”). After selecting one of those options, they keypad returns to the default state.

Philips sued Acer and others for infringement based upon their use of the Chrome and Android OS — that led Google to petition for inter partes review (IPR).

In its final decision, the PTAB sided with the patentee in holding that Google failed to prove that the claims were obvious. On appeal, the Federal Circuit has reversed.

On appeal here, the Federal circuit has reversed the PTAB’s final decision siding with the patentee and holding that Google failed to prove that the claims were obvious. The basic issue here is that there is only a minimal difference between Philips’ claimed invention and the key prior art reference. The court explains:

The parties do not dispute that the [Philips’] ’913 patent claim differs from that Sakata II method in only one respect. In the ’913 patent claim, after a secondary character is selected, the relevant key “return[s] . . . to the default state” rather than, as in the described Sakata II method, changing to the selected secondary character.

It was also clear that the “return-to-default” option was available and familiar to someone skilled in the art (e.g. shift key). Philips argued that particular step would not have been obvious-to-try since it one of many potential keypad techniques available. On appeal, the Federal Circuit rejected the “wide-scope inquiry” as a red herring in this case — finding language from KSR directly on point:

[W]hen a patent claims a structure already known in the prior art that is altered by the mere substitution of one element for another known in the field, the combination must do more than yield a predictable result.”

KSR International Co. v. Teleflex Inc. (KSR), 550 U.S. 398 (2007). The Fed. Cir. explained somewhat obliquely that:

[T]he obvious-to-try inquiry at least sometimes must focus on known options at what is undisputedly the sole point of novelty in the claim at issue.

See Perfect Web Techs., Inc. v. InfoUSA, Inc., 587 F.3d 1324 (Fed. Cir. 2009). The practical point here is that inventions with a sole-point-of-novelty set themselves up as a target for an obviousness finding because the court will ask “if the sole contested step of the claim at issue was obvious to try, taking the remaining steps as a given.”

In this case, the Court found additional reasons for obviousness — notably the primary prior art reference was actually an improvement over prior return-to-default techniques.

Sakata II itself asserts that the character substitution at the last step provides an efficiency benefit over the evident alternative of requiring that the secondary-character menu be summoned each time one of those characters was to be re-used. . . . This efficiency assertion is on its face a comparative one, and what is plainly being compared to the Sakata II choice is the no-substitution option—where the primary character returns to the key upon disappearance of the secondary-character menu. That is Philips’s returnto-default claim element.

Slip Op. In the end, the appellate panel did not appear to directly fault the Board’s factual conclusions but rather Board’s legal analysis — in particular the meaning of “obvious-to-try” and its impact on the ultimate (legal) conclusion of obviousness.

We hold that claims 1 and 3–16 of the ’913 patent are unpatentable for obviousness. The Board’s decision is reversed.