When a Copyright Owner Gets Only a $1,000 Judgment in Federal Court, They’re the Real Losers–McDermott v. KMC

Technology & Marketing Law Blog 2024-11-16

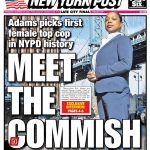

Matthew McDermott is a freelance photographer. The New York Post hired him to take photos of NYC police commissioner Keechant Sewell, paying him a day rate of $470. McDermott kept the copyright to those photo and granted NY Post a license. The New York Post story. The article included multiple photos of Sewell, including the photo in question, and the Post apparently liked the image so much that they used a portion of the photo as the background for the newspaper cover that day (see screenshot at right).

Matthew McDermott is a freelance photographer. The New York Post hired him to take photos of NYC police commissioner Keechant Sewell, paying him a day rate of $470. McDermott kept the copyright to those photo and granted NY Post a license. The New York Post story. The article included multiple photos of Sewell, including the photo in question, and the Post apparently liked the image so much that they used a portion of the photo as the background for the newspaper cover that day (see screenshot at right).

The defendant, Kalita Mukul Creative, ran community-focused newsletters. It’s a small operation, with a 2022 budget of under $1M/year. The defendant published a bio on Sewell and included one of McDermott’s photos–apparently sourced from an unrelated Instagram account (possibly another infringer, or perhaps that account has a fair use defense?). In 16 months, the bio generated less than 100 views.

McDermott, represented by the Sanders Law Group, sued KMC for copyright infringement. Covington & Burling defended KMC, apparently pro bono. The defendant conceded summary judgment on liability, and the court held a trial on damages. This post covers the court’s ruling following the damages trial.

Setting the Damages Range

The court rejects KMC’s innocent infringement defense. The court acknowledges that KMC “demonstrated a subjective good faith belief in its innocence.” However, the court says that assuming that photos online are free-to-use is not objectively reasonable.

At the same time, the court rejects McDermott’s allegations of willful infringement. McDermott argued that KMC was sophisticated about copyright law because the person who attached the photo to the bio had a journalism background. The court says that allegation isn’t enough to overcome the defendant’s subjective good faith belief, as well as the meager (if ill-informed) steps that KMC did take to adhere to copyright law. Thus, the court summarizes: “Its compliance system may have been imperfect and its conduct negligent, but Defendant did not act recklessly.”

Damages Calculation

Having ruled out the bases for adjusting statutory damages, the applicable damages range in this case is $750-$30,000. McDermott had not actually licensed the photo to anyone else to set a baseline license fee. Instead, McDermott asked for $13k, based on an estimate provided by Getty Image’s revenue calculator, quintupled because why not. The court runs through multiple considerations:

- Defendant’s state of mind. Not willful.

- Defendant’s financial benefit. “Defendant earned no revenue from the Article, and even if many people were encouraged to read the Article, almost no one did: it received fewer than 100 views over its entire online life.”

- Plaintiff’s lost revenue. The court says it has reasons “to doubt the reliability of Plaintiff’s Getty Estimate.”

- Deterrence. The court says “this case makes for a poor deterrence vehicle” because KMC actually tried to respect copyrights.

- The parties’ conduct. “Defendant immediately removed the infringing Photo upon having learned of it, [] made an offer of judgment in the amount of $2,500 in September 2023, and [] later conceded liability so as to advance the termination of this action.” [The $2,500 amount was suggested by the presiding judge at a settlement conference, which the defendant turned into an offer of judgment.] On the other hand, the plaintiff never sent a C&D.

These factors push the court towards the bottom end of the statutory damages range: “the Court finds that an award of $940—representing double Plaintiff’s daily rate at the time he took the Photo—to be appropriate in this case.”

Attorneys’ Fees

The plaintiff requested $120k in fees and costs. Seriously? The photo had less than 100 views, so $120k of legal work in response to such a low-scale infringement strikes me as excessive. The court doesn’t buy it: “even though Plaintiff’s counsel took a maximalist approach to this litigation, their efforts led to what can only be described as a suboptimal, and yet predictable, result.” The court denigrates the plaintiff’s advocacy as, at times, “overcomplicated and unreliable,” “bizarrely critic[al],” and “undignified,” and says “the record points to unreasonable conduct by Plaintiff” (because their settlement demands were linked to their ever-growing attorneys’ fees).

The court was especially irritated by the aspertions plaintiff cast on pro bono defense counsel:

Plaintiff’s argument suggests that defense counsel put its own interests before its client’s. Plaintiff’s counsel should think long and hard before making such serious accusations in the future. That is especially true on a record like this one, which evidences a vigorous and diligent defense of this action.

Given that it said the plaintiff engaged in unreasonable conduct, the court could have awarded some or all of the defense’s attorneys’ fees. Perhaps the defendant didn’t request them because the lawyers were pro bono anyway. In that respect, the plaintiff might consider itself lucky that the 505 fee shift didn’t backfire on it.

Implications

This case involved one unmonetized photo viewed less than 100 times. That produced 60 docket entries, a trial on damages, and a 12,000 word/37 page opinion following the trial on damages. If I’m charitable in my characterizations, the amount of resources invested in this case vastly dwarfs the case’s value.

It’s likely that neither side’s lawyers were working on an hourly basis. I suspect the plaintiff’s lawyers were on contingency. Even then, the plaintiff asked for about $13k of statutory damages as its fallback position, and getting that full award wouldn’t have produced a very lucrative contingency fee award. The court indicates that at some point this case really was all about the plaintiff’s attorneys’ fees, not the copyright merits themselves. Meanwhile, the case suggests that Covington and Burling took this case pro bono (a little surprising, because the court says the defendant was for-profit), so their defense wasn’t driven by standard client cost concerns. However we get there, the overall litigation enterprise here makes no economic sense.

An obvious question: why did the plaintiff choose federal court over the CCB when the CCB was designed precisely for the facts of this case? The CCB damage awards have been in the $1k range, so the dollar value might have been about the same, but at a much lower litigation cost. There would not have been 60 docket entries or a trial on damages in the CCB. At the same time, the CCB usually cannot award attorneys’ fees, and that became a material element of the case. Whatever the reason, this case’s adjudication in federal court and very low damages award is partially an indictment of the CCB’s failure to occupy the niche it was designed to address.

Case Citation: McDermott v. Kalita Mukul Creative Inc., 2024 WL 4799751 (E.D.N.Y. Nov. 15, 2024)

The post When a Copyright Owner Gets Only a $1,000 Judgment in Federal Court, They’re the Real Losers–McDermott v. KMC appeared first on Technology & Marketing Law Blog.