The Big Lock-Down Math-Off, Match 14

The Aperiodical 2020-05-07

Welcome to the 14th match in this year’s Big Math-Off. Take a look at the two interesting bits of maths below, and vote for your favourite.

You can still submit pitches, and anyone can enter: instructions are in the announcement post.

Here are today’s two pitches.

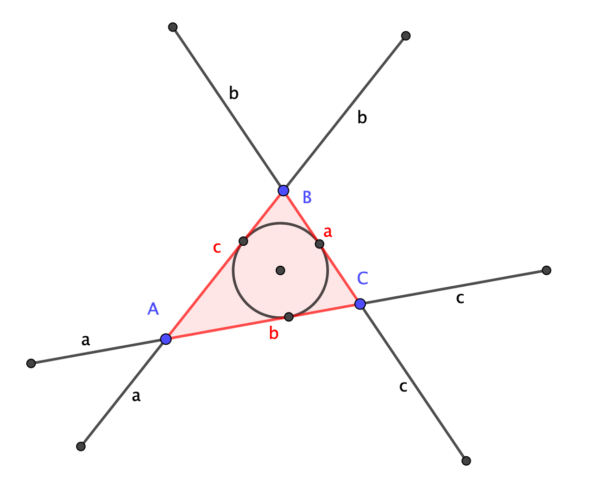

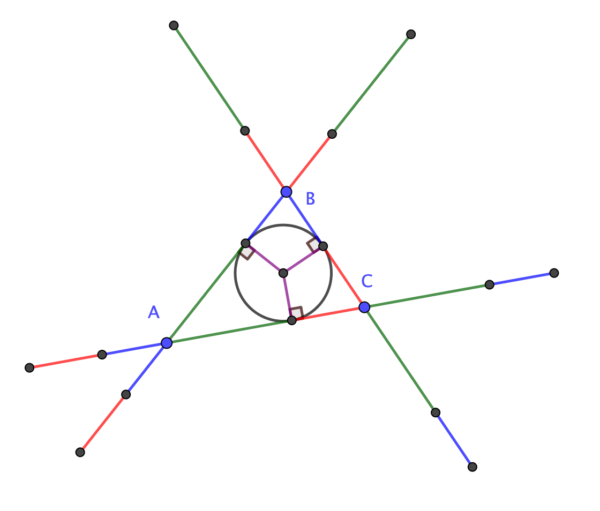

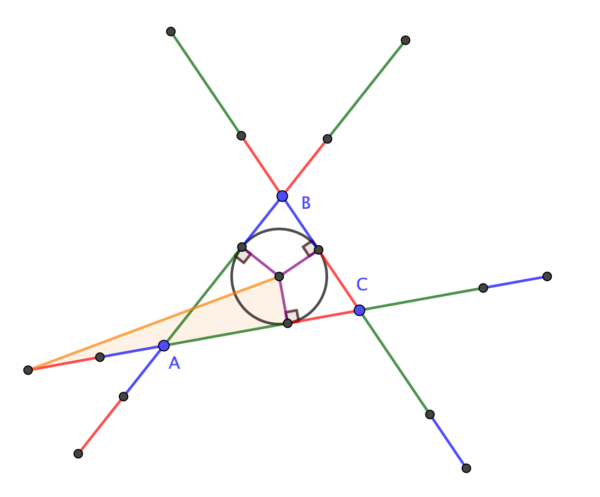

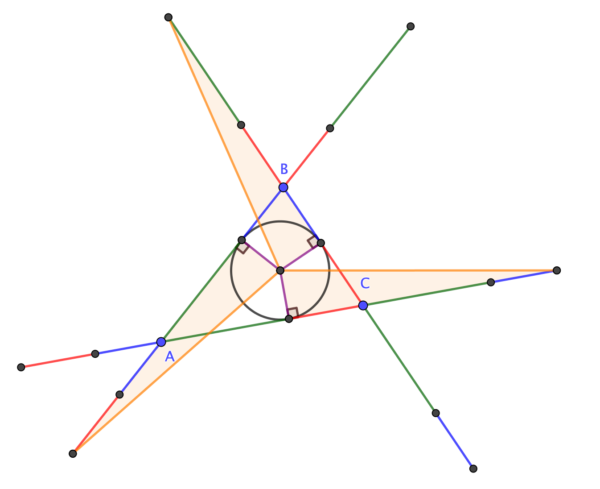

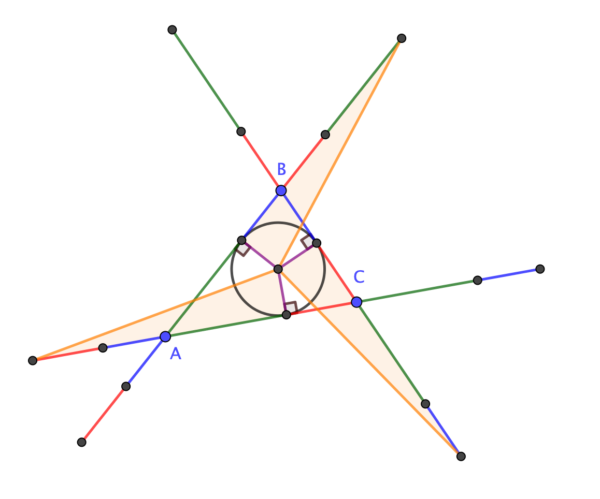

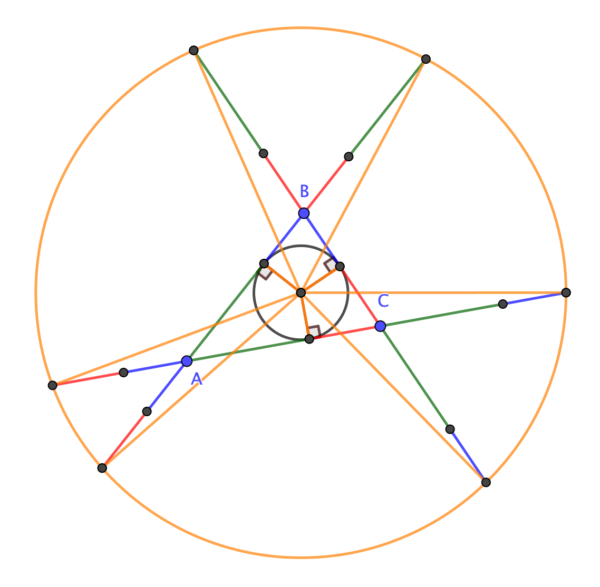

Colin Beveridge – Conway’s Circle, a proof without words

Colin blogs at flyingcoloursmaths.co.uk and tweets at @icecolbeveridge.

Given triangle ABC, extend sides \( a \) and \( c \) through B by a length equal to side \( b \). Similarly, extend sides \( b \) and \( c \) through A and sides \(a \) and \( b \) through C. Then the ends of these sides lie on a circle (the Conway Circle) which is concentric with the incircle of ABC.

QEF.

Alex Cutbill – The difference of two squares with a twist

Alex is a freelance maths education consultant. He tweets at @intersectarian.

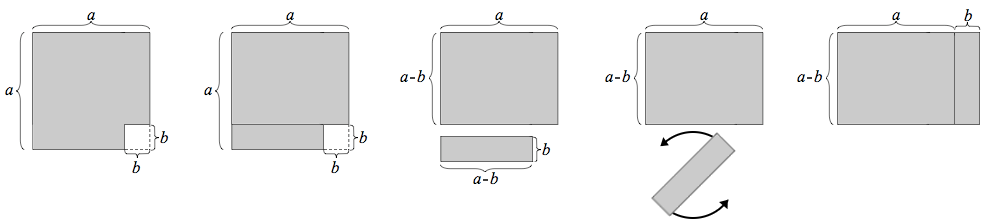

The difference of two squares, $a^2-b^2$, can be factorised as $(a+b)(a-b)$.

This lovely little identity can be proved algebraically using the distributive and commutative laws:

\[ (a+b)(a-b) \equiv a(a-b) + b(a-b) \equiv a^2-ab+ba-b^2 \equiv a^2-ab+ab-b^2 \equiv a^2-b^2 \]

But, like many things, it’s much nicer to prove it with pictures. Here are the graphics from Wikipedia:

Image from Wikimedia Commons by Navigatr85 and Vsb, used under the CC0 licence.

Image from Wikimedia Commons by Navigatr85 and Vsb, used under the CC0 licence.This geometric proof compares favourably with the original algebraic proof, not least because it goes in the right direction, from $a^2-b^2$ to $(a+b)(a-b)$. The algebraic proof feels a bit like factorising 28,554,961 by multiplying 6,899 and 4,139 together.

Anyway, let me come to the point of my pitch: you’re probably already sold on this geometric proof, having seen it long, long ago, but there’s another geometric proof which you may not have seen.

Take a while to get used to the perspective – it’s in 3D! – and then slowly increase the value of θ to 180 by moving the slider.

I think of both geometric proofs in terms of physical manipulatives. Demonstrating the first proof involves rearranging two blocks, carefully positioning them relative to each other. The second proof suggests a single manipulative, whose two halves are held together by the axle which provides the only affordance; all you can do is twist, and with a twist the identity is proved. To me, the second manipulative, and hence the second proof, is more elegant.

I can’t take credit for this proof; while I rediscovered it independently, I subsequently found it in the wild:

Why difference of two squares? pic.twitter.com/PWsM6iiEsK

— Jennifer Fairbanks (@JenFairbanks8) February 12, 2015

I’d be interested to hear from you if you’ve seen this proof elsewhere. I’d also be interested to hear from you if you can make me the twisty manipulative I describe above! (And so, the ulterior motive for sharing this pitch is revealed.) If, like me, your practical skills are practically non-existent, you might like to consider the following puzzle instead. It also comes with a twist!

What are the area and perimeter of this not-a-parallelogram? #geometry pic.twitter.com/uvN9VSa7Fl

— Alex Cutbill (@intersectarian) April 22, 2020

So, which bit of maths made you say “Aha!” the loudest? Vote:

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.The poll closes at 9am BST on Saturday the 9th, when the next match starts.

If you’ve been inspired to share your own bit of maths, look at the announcement post for how to send it in. The Big Lockdown Math-Off will keep running until we run out of pitches or we’re allowed outside again, whichever comes first.