New Methods Solve Old Problems

Gödel’s Lost Letter and P=NP 2024-03-26

Really old ones, in this case

Ben Cohen writes the “Science of Success” column for The Wall Street Journal. It is about what makes people, teams and ideas work out in business, culture, and beyond.

His recent one was about Luke Farritor, who was a college student majoring in computer science and interning at SpaceX, and who began working on a problem that captivated many of the world’s top geeks.

The problem was about trying to read ancient papyrus scrolls that have gone unread for millennia. As Cohen—or his headline writer—tells it: “Then came a $1 million competition for AI geeks, and some of the World’s Smartest Young Minds Cracked this 2,000-Year-Old Mystery.”

Black On Black

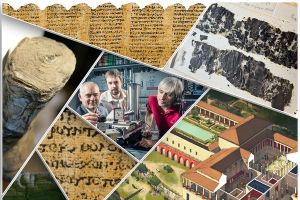

The scrolls in question were from a library in the Roman town of Herculaneum, which was destroyed by the eruptions of Vesuvius in 79 CE. The pyroclastic flows carbonized the papyri without reducing them to ash. The library was discovered when Herculaneum began to be excavated in the 18th century. Here is what some of the scrolls look like today:

Getty Museum source

Getty Museum sourceCommon belief holds that the library began in the century before the eruption as the collection of the poet and philosopher Philodemus. Ancient references raise the expectation that the library would have had complete collections of the writings of Plato and Aristotle and other luminaries, many of whose works are attested but have no surviving known copy. If the over 1,800 surviving scrolls could somehow be read, numerous lost works could be recovered.

This prospect tempted people in the 1700s to try to open the least-blackened scrolls. Doing so generally destroyed more than was recovered. Even when scrolls were opened, there was often nothing to be seen. Many were written in charcoal or carbon-based ink, which left no visual or tangible distinction from the blackened papyrus.

The black-on-black fusion even defied modern attempts to read the scrolls with X-ray imaging. CT scans made usable 3D models of the scrolls, but again without clearly divulging ink patterns. The hidden question became: what other aspect of the writing might still leave decipherable traces? Finding the traces became the province of computational more than physically technological methods.

Husker Do

The key is related in the article, “Husker is first to decode word on ancient scroll.”

The word our readers need to decode first is “husker.” Is a husker like a hacker with a different shade of meaning? In this instance, perhaps yes. But in general, it means anyone at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln, whose demonym is Cornhuskers.

A husk is something you might associate with crackling on becoming dry, or when burnt. As a noun, crackle means a fine surface network of cracks or veins. Farritor chanced across a social media post by a former NASA software engineer, Casey Handmer, noting a crackle pattern in one part of a CT image that seemed to correspond to a Greek letter. Farritor stared at other images available to him until he could confirm it visually.

Upon finding enough examples he could label, Farritor was able to code a machine learning model to recognize crackle patterns and classify them as potential letters. Here is where a bank of known text from physically unrolled scrolls paid a dividend after much sacrifice. Farritor was able to decode a clear long word— meaning “purple”:

That is to say, the carbonization preserved some of the scrolls’ facility to remember—the meaning of “husker” in Danish or Norwegian—what had been laid on their surface by human hands. The effort has seen further progress with Youssef Nader, a biorobotics graduate student in Berlin, able to extend the readable area of Farritor’s segment, and larger findings in other scrolls.

Open Problems

The solution was based on AI methods. One wonders if it such new methods could eventually solve open problems in mathematics. We could facetiously say that maybe Pierre de Fermat left patterns in his copy of Diophantus’s Arithmetic, say impressions of checkmarks in the text, that would enable reconstructing the train of thought that led him to think he had proved his famous Last Theorem. Maybe there really is a way to infer trains of thought from how papers are written in general?