The Problem of Human Specialness in the Age of AI

Shtetl-Optimized 2024-02-12

Here, as promised in my last post, is a written version of the talk I delivered a couple weeks ago at MindFest in Florida, entitled “The Problem of Human Specialness in the Age of AI.” The talk is designed as one-stop shopping, summarizing many different AI-related thoughts I’ve had over the past couple years (and earlier).

1. INTRO

Thanks so much for inviting me! I’m not an expert in AI, let alone mind or consciousness. Then again, who is?

For the past year and a half, I’ve been moonlighting at OpenAI, thinking about what theoretical computer science can do for AI safety. I wanted to share some thoughts, partly inspired by my work at OpenAI but partly just things I’ve been wondering about for 20 years. These thoughts are not directly about “how do we prevent super-AIs from killing all humans and converting the galaxy into paperclip factories?”, nor are they about “how do we stop current AIs from generating misinformation and being biased?,” as much attention as both of those questions deserve (and are now getting). In addition to “how do we stop AGI from going disastrously wrong?,” I find myself asking “what if it goes right? What if it just continues helping us with various mental tasks, but improves to where it can do just about any task as well as we can do it, or better? Is there anything special about humans in the resulting world? What are we still for?”

2. LARGE LANGUAGE MODELS

I don’t need to belabor for this audience what’s been happening lately in AI. It’s arguably the most consequential thing that’s happened in civilization in the past few years, even if that fact was temporarily masked by various ephemera … y’know, wars, an insurrection, a global pandemic … whatever, what about AI?

I assume you’ve all spent time with ChatGPT, or with Bard or Claude or other Large Language Models, as well as with image models like DALL-E and Midjourney. For all their current limitations—and we can discuss the limitations—in some ways these are the thing that was envisioned by generations of science fiction writers and philosophers. You can talk to them, and they give you a comprehending answer. Ask them to draw something and they draw it.

I think that, as late as 2019, very few of us expected this to exist by now. I certainly didn’t expect it to. Back in 2014, when there was a huge fuss about some silly ELIZA-like chatbot called “Eugene Goostman” that was falsely claimed to pass the Turing Test, I asked around: why hasn’t anyone tried to build a much better chatbot, by (let’s say) training a neural network on all the text on the Internet? But of course I didn’t do that, nor did I know what would happen when it was done.

The surprise, with LLMs, is not merely that they exist, but the way they were created. Back in 1999, you would’ve been laughed out of the room if you’d said that all the ideas needed to build an AI that converses with you in English already existed, and that they’re basically just neural nets, backpropagation, and gradient descent. (With one small exception, a particular architecture for neural nets called the transformer, but that probably just saves you a few years of scaling anyway.) Ilya Sutskever, cofounder of OpenAI (who you might’ve seen something about in the news…), likes to say beyond those simple ideas, you only needed three ingredients:

(1) a massive investment of computing power, (2) a massive investment of training data, and (3) faith that your investments would pay off!

Crucially, and even before you do any reinforcement learning, GPT-4 clearly seems “smarter” than GPT-3, which seems “smarter” than GPT-2 … even as the biggest ways they differ are just the scale of compute and the scale of training data! Like,

- GPT-2 struggled with grade school math.

- GPT-3.5 can do most grade school math but it struggles with undergrad material.

- GPT-4, right now, can almost certainly pass most undergraduate math and science classes at top universities (I mean, the ones without labs or whatever!), and possibly the humanities classes too (those might even be easier for GPT-4 than the science classes, but I’m much less confident about it). But it still struggles with, for example, the International Math Olympiad. How insane, that this is now where we have to place the bar!

Obvious question: how far will this sequence continue? There are certainly a least a few more orders of magnitude of compute before energy costs become prohibitive, and a few more orders of magnitude of training data before we run out of public Internet. Beyond that, it’s likely that continuing algorithmic advances will simulate the effect of more orders of magnitude of compute and data than however many we actually get.

So, where does this lead?

(Note: ChatGPT agreed to cooperate with me to help me generate the above image. But it then quickly added that it was just kidding, and the Riemann Hypothesis is still open.)

3. AI SAFETY

Of course, I have many friends who are terrified (some say they’re more than 90% confident and few of them say less than 10%) that not long after that, we’ll get this…

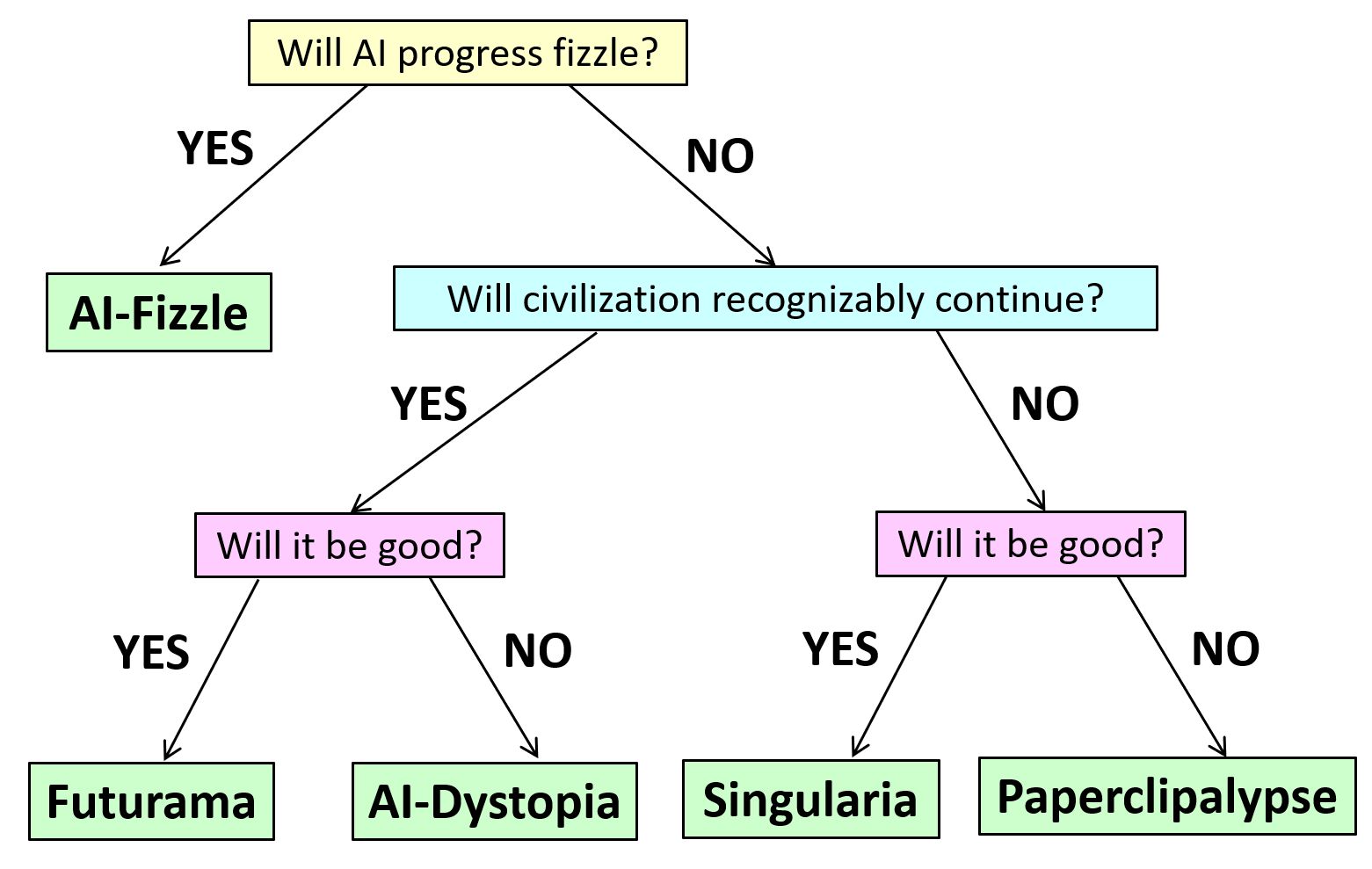

But this isn’t the only possibility smart people take seriously.

Another possibility is that the LLM progress fizzles before too long, just like previous bursts of AI enthusiasm were followed by AI winters. Note that, even in the ultra-conservative scenario, LLMs will probably still be transformative for the economy and everyday life, maybe even as transformative as the Internet. But they’ll just seem like better and better GPT-4’s, without ever seeming qualitatively different from GPT-4, and without anyone ever turning them into stable autonomous agents and letting them loose in the real world to pursue goals the way we do.

A third possibility is that AI will continue progressing through our lifetimes as quickly as we’ve seen it progress over the past 5 years, but even as that suggests that it’ll surpass you and me, surpass John von Neumann, become to us as we are to chimpanzees … we’ll still never need to worry about it treating us the way we’ve treated chimpanzees. Either because we’re projecting and that’s just totally not a thing that AIs trained on the current paradigm would tend to do, or because we’ll have figured out by then how to prevent AIs from doing such things. Instead, AI in this century will “merely” change human life by maybe as much as it changed over the last 20,000 years, in ways that might be incredibly good, or incredibly bad, or both depending on who you ask.

If you’ve lost track, here’s a decision tree of the various possibilities that my friend (and now OpenAI allignment colleague) Boaz Barak and I came up with.

4. JUSTAISM AND GOALPOST-MOVING

Now, as far as I can tell, the empirical questions of whether AI will achieve and surpass human performance at all tasks, take over civilization from us, threaten human existence, etc. are logically distinct from the philosophical question of whether AIs will ever “truly think,” or whether they’ll only ever “appear” to think. You could answer “yes” to all the empirical questions and “no” to the philosophical question, or vice versa. But to my lifelong chagrin, people constantly munge the two questions together!

A major way they do so, is with what we could call the religion of Justaism.

- GPT is justa next-token predictor.

- It’s justa function approximator.

- It’s justa gigantic autocomplete.

- It’s justa stochastic parrot.

- And, it “follows,” the idea of AI taking over from humanity is justa science-fiction fantasy, or maybe a cynical attempt to distract people from AI’s near-term harms.

As someone once expressed this religion on my blog: GPT doesn’t interpret sentences, it only seems-to-interpret them. It doesn’t learn, it only seems-to-learn. It doesn’t judge moral questions, it only seems-to-judge. I replied: that’s great, and it won’t change civilization, it’ll only seem-to-change it!

A closely related tendency is goalpost-moving. You know, for decades chess was the pinnacle of human strategic insight and specialness, and that lasted until Deep Blue, right after which, well of course AI can cream Garry Kasparov at chess, everyone always realized it would, that’s not surprising, but Go is an infinitely richer, deeper game, and that lasted until AlphaGo/AlphaZero, right after which, of course AI can cream Lee Sedol at Go, totally expected, but wake me up when it wins Gold in the International Math Olympiad. I bet $100 against my friend Ernie Davis that the IMO milestone will happen by 2026. But, like, suppose I’m wrong and it’s 2030 instead … great, what should be the next goalpost be?

Indeed, we might as well formulate a thesis, which despite the inclusion of several weasel phrases I’m going to call falsifiable:

Given any game or contest with suitably objective rules, which wasn’t specifically constructed to differentiate humans from machines, and on which an AI can be given suitably many examples of play, it’s only a matter of years before not merely any AI, but AI on the current paradigm (!), matches or beats the best human performance.

Crucially, this Aaronson Thesis (or is it someone else’s?) doesn’t necessarily say that AI will eventually match everything humans do … only our performance on “objective contests,” which might not exhaust what we care about.

Incidentally, the Aaronson Thesis would seem to be in clear conflict with Roger Penrose’s views, which we heard about from Stuart Hameroff’s talk yesterday. The trouble is, Penrose’s task is “just see that the axioms of set theory are consistent” … and I don’t know how to gauge performance on that task, any more than I know how to gauge performance on the task, “actually taste the taste of a fresh strawberry rather than merely describing it.” The AI can always say that it does these things!

5. THE TURING TEST

This brings me to the original and greatest human vs. machine game, one that was specifically constructed to differentiate the two: the Imitation Game, which Alan Turing proposed in an early and prescient (if unsuccessful) attempt to head off the endless Justaism and goalpost-moving. Turing said: look, presumably you’re willing to regard other people as conscious based only on some sort of verbal interaction with them. So, show me what kind of verbal interaction with another person would lead you to call the person conscious: does it involve humor? poetry? morality? scientific brilliance? Now assume you have a totally indistinguishable interaction with a future machine. Now what? You wanna stomp your feet and be a meat chauvinist?

(And then, for his great attempt to bypass philosophy, fate punished Turing, by having his Imitation Game itself provoke a billion new philosophical arguments…)

6. DISTINGUISHING HUMANS FROM AIS

Although I regard the Imitation Game as, like, one of the most important thought experiments in the history of thought, I concede to its critics that it’s generally not what we want in practice.

It now seems probable that, even as AIs start to do more and more work that used to be done by doctors and lawyers and scientists and illustrators, there will remain straightforward ways to distinguish AIs from humans—either because customers want there to be, or governments force there to be, or simply because indistinguishability wasn’t what was wanted or conflicted with other goals.

Right now, like it or not, a decent fraction of all high-school and college students on earth are using ChatGPT to do their homework for them. For that reason among others, this question of how to distinguish humans from AIs, this question from the movie Blade Runner, has become a big practical question in our world.

And that’s actually one of the main things I’ve thought about during my time at OpenAI. You know, in AI safety, people keep asking you to prognosticate decades into the future, but the best I’ve been able to do so far was see a few months into the future, when I said: “oh my god, once everyone starts using GPT, every student will want to use it to cheat, scammers and spammers will use it too, and people are going to clamor for some way to determine provenance!”

In practice, often it’s easy to tell what came from AI. When I get comments on my blog like this one:

“Erica Poloix,” July 21, 2023: Well, it’s quite fascinating how you’ve managed to package several misconceptions into such a succinct comment, so allow me to provide some correction. Just as a reference point, I’m studying physics at Brown, and am quite up-to-date with quantum mechanics and related subjects.

…

The bigger mistake you’re making, Scott, is assuming that the Earth is in a ‘mixed state’ from the perspective of the universal wavefunction, and that this is somehow an irreversible situation. It’s a misconception that common, ‘classical’ objects like the Earth are in mixed states. In the many-worlds interpretation, for instance, even macroscopic objects are in superpositions – they’re just superpositions that look classical to us because we’re entangled with them. From the perspective of the universe’s wavefunction, everything is always in a pure state.

As for your claim that we’d need to “swap out all the particles on Earth for ones that are already in pure states” to return Earth to a ‘pure state,’ well, that seems a bit misguided. All quantum systems are in pure states before they interact with other systems and become entangled. That’s just Quantum Mechanics 101.

I have to say, Scott, your understanding of quantum physics seems to be a bit, let’s say, ‘mixed up.’ But don’t worry, it happens to the best of us. Quantum Mechanics is counter-intuitive, and even experts struggle with it. Keep at it, and try to brush up on some more fundamental concepts. Trust me, it’s a worthwhile endeavor.

… I immediately say, either this came from an LLM or it might as well have. Likewise, apparently hundreds of students have been turning in assignments that contain text like, “As a large language model trained by OpenAI…”—easy to catch!

But what about the slightly more sophisticated cheaters? Well, people have built discriminator models to try to distinguish human from AI text, such as GPTZero. While these distinguishers can get well above 90% accuracy, the danger is that they’ll necessarily get worse as the LLMs get better.

So, I’ve worked on a different solution, called watermarking. Here, we use the fact that LLMs are inherently probabilistic — that is, every time you submit a prompt, they’re sampling some path through a branching tree of possibilities for the sequence of next tokens. The idea of watermarking is to steer the path using a pseudorandom function, so that it looks to a normal user indistinguishable from normal LLM output, but secretly it encodes a signal that you can detect if you know the key.

I came up with a way to do that in Fall 2022, and others have since independently proposed similar ideas. I should caution you that this hasn’t been deployed yet—OpenAI, along with DeepMind and Anthropic, want to move slowly and cautiously toward deployment. And also, even when it does get deployed, anyone who’s sufficiently knowledgeable and motivated will be able to remove the watermark, or produce outputs that aren’t watermarked to begin with.

7. THE FUTURE OF PEDAGOGY

But as I talked to my colleagues about watermarking, I was surprised that they often objected to it on a completely different ground, one that had nothing to do with how well it can work. They said: look, if we all know students are going to rely on AI in their jobs, why shouldn’t they be allowed to rely on it in their assignments? Should we still force students to learn to do things if AI can now do them just as well?

And there are many good pedagogical answers you can give: we still teach kids spelling and handwriting and arithmetic, right? Because, y’know, we haven’t yet figured out how to instill higher-level conceptual understanding without all that lower-level stuff as a scaffold for it.

But I already think about this in terms of my own kids. My 11-year-old daughter Lily enjoys writing fantasy stories. Now, GPT can also churn out short stories, maybe even technically “better” short stories, about such topics as tween girls who find themselves recruited by wizards to magical boarding schools that are not Hogwarts and totally have nothing to do with Hogwarts. But here’s a question: from this point on, will Lily’s stories ever surpass the best AI-written stories? When will the curves cross? Or will AI just continue to stay ahead?

8. WHAT DOES “BETTER” MEAN?

But, OK, what do we even mean by one story being “better” than another? Is there anything objective behind such judgments?

I submit that, when we think carefully about what we really value in human creativity, the problem goes much deeper than just “is there an objective way to judge”?

To be concrete, could there be an AI that was “as good at composing music as the Beatles”?

For starters, what made the Beatles “good”? At a high level, we might decompose it into

- broad ideas about the direction that 1960s music should go in, and

- technical execution of those ideas.

Now, imagine we had an AI that could generate 5000 brand-new songs that sounded like more “Yesterday”s and “Hey Jude”s, like what the Beatles might have written if they’d somehow had 10x more time to write at each stage of their musical development. Of course this AI would have to be fed the Beatles’ back-catalogue, so that it knew what target it was aiming at.

Most people would say: ah, this shows only that AI can match the Beatles in #2, in technical execution, which was never the core of their genius anyway! Really we want to know: would the AI decide to write “A Day in the Life” even though nobody had written anything like it before?

Recall Schopenhauer: “Talent hits a target no one else can hit, genius hits a target no one else can see.” Will AI ever hit a target no one else can see?

But then there’s the question: supposing it does hit such a target, will we know? Beatles fans might say that, by 1967 or so, the Beatles were optimizing for targets that no musician had ever quite optimized for before. But—and this is why they’re so remembered—they somehow successfully dragged along their entire civilization’s musical objective function so that it continued to match their own. We can now only even judge music by a Beatles-influenced standard, just like we can only judge plays by a Shakespeare-influenced standard.

In other branches of the wavefunction, maybe a different history led to different standards of value. But in this branch, helped by their technical talents but also by luck and force of will, Shakespeare and the Beatles made certain decisions that shaped the fundamental ground rules of their fields going forward. That’s why Shakespeare is Shakespeare and the Beatles are the Beatles.

(Maybe, around the birth of professional theater in Elizabethan England, there emerged a Shakespeare-like ecological niche, and Shakespeare was the first one with the talent, luck, and opportunity to fill it, and Shakespeare’s reward for that contingent event is that he, and not someone else, got to stamp his idiosyncracies onto drama and the English language forever. If so, art wouldn’t actually be that different from science in this respect! Einstein, for example, was simply the first guy both smart and lucky enough to fill the relativity niche. If not him, it would’ve surely been someone else or some group sometime later. Except then we’d have to settle for having never known Einstein’s gedankenexperiments with the trains and the falling elevator, his summation convention for tensors, or his iconic hairdo.)

9. AIS’ BURDEN OF ABUNDANCE AND HUMANS’ POWER OF SCARCITY

If this is how it works, what does it mean for AI? Could AI reach the “pinnacle of genius,” by dragging all of humanity along to value something new and different, as is said to be the true mark of Shakespeare and the Beatles’ greatness? And: if AI could do that, would we want to let it?

When I’ve played around with using AI to write poems, or draw artworks, I noticed something funny. However good the AI’s creations were, there were never really any that I’d want to frame and put on the wall. Why not? Honestly, because I always knew that I could generate a thousand others on the exact same topic that were equally good, on average, with more refreshes of the browser window. Also, why share AI outputs with my friends, if my friends can just as easily generate similar outputs for themselves? Unless, crucially, I’m trying to show them my own creativity in coming up with the prompt.

By its nature, AI—certainly as we use it now!—is rewindable and repeatable and reproducible. But that means that, in some sense, it never really “commits” to anything. For every work it generates, it’s not just that you know it could’ve generated a completely different work on the same subject that was basically as good. Rather, it’s that you can actually make it generate that completely different work by clicking the refresh button—and then do it again, and again, and again.

So then, as long as humanity has a choice, why should we ever choose to follow our would-be AI genius along a specific branch, when we can easily see a thousand other branches the genius could’ve taken? One reason, of course, would be if a human chose one of the branches to elevate above all the others. But in that case, might we not say that the human had made the “executive decision,” with some mere technical assistance from the AI?

I realize that, in a sense, I’m being completely unfair to AIs here. It’s like, our Genius-Bot could exercise its genius will on the world just like Certified Human Geniuses did, if only we all agreed not to peek behind the curtain to see the 10,000 other things Genius-Bot could’ve done instead. And yet, just because this is “unfair” to AIs, doesn’t mean it’s not how our intuitions will develop.

If I’m right, it’s humans’ very ephemerality and frailty and mortality, that’s going to remain as their central source of their specialness relative to AIs, after all the other sources have fallen. And we can connect this to much earlier discussions, like, what does it mean to “murder” an AI if there are thousands of copies of its code and weights on various servers? Do you have to delete all the copies? How could whether something is “murder” depend on whether there’s a printout in a closet on the other side of the world?

But we humans, you have to grant us this: at least it really means something to murder us! And likewise, it really means something when we make one definite choice to share with the world: this is my artistic masterpiece. This is my movie. This is my book. Or even: these are my 100 books. But not: here’s any possible book that you could possibly ask me to write. We don’t live long enough for that, and even if we did, we’d unavoidably change over time as we were doing it.

10. CAN HUMANS BE PHYSICALLY CLONED?

Now, though, we have to face a criticism that might’ve seemed exotic until recently. Namely, who says humans will be frail and mortal forever? Isn’t it shortsighted to base our distinction between humans on that? What if someday we’ll be able to repair our cells using nanobots, even copy the information in them so that, as in science fiction movies, a thousand doppelgangers of ourselves can then live forever in simulated worlds in the cloud? And that then leads to very old questions of: well, would you get into the teleportation machine, the one that reconstitutes a perfect copy of you on Mars while painlessly euthanizing the original you? If that were done, would you expect to feel yourself waking up on Mars, or would it only be someone else a lot like you who’s waking up?

Or maybe you say: you’d wake up on Mars if it really was a perfect physical copy of you, but in reality, it’s not physically possible to make a copy that’s accurate enough. Maybe the brain is inherently noisy or analog, and what might look to current neuroscience and AI like just nasty stochastic noise acting on individual neurons, is the stuff that binds to personal identity and conceivably even consciousness and free will (as opposed to cognition, where we all but know that the relevant level of description is the neurons and axons)?

This is the one place where I agree with Penrose and Hameroff that quantum mechanics might enter the story. I get off their train to Weirdville very early, but I do take it to that first stop!

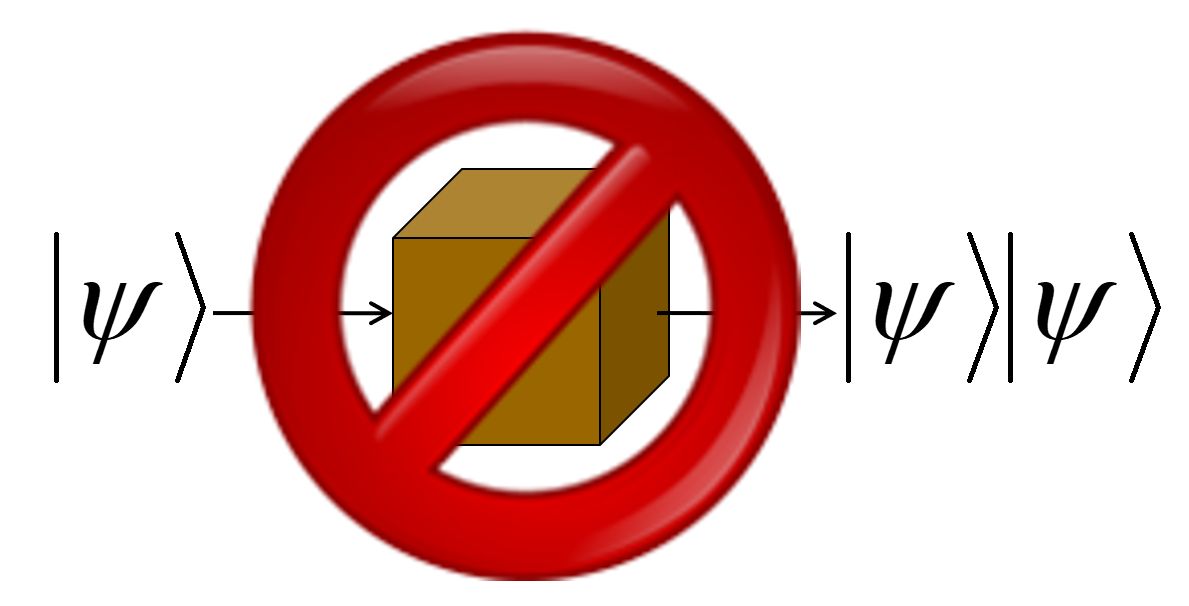

See, a fundamental fact in quantum mechanics is called the No-Cloning Theorem.

It says that there’s no way to make a perfect copy of an unknown quantum state. Indeed, when you measure a quantum state, not only do you generally fail to learn everything you need to make a copy of it, you even generally destroy the one copy that you had! Furthermore, this is not a technological limitation of current quantum Xerox machines—it’s inherent to the known laws of physics, to how QM works. In this respect, at least, qubits are more like priceless antiques than they are like classical bits.

Eleven years ago, I had this essay called The Ghost in the Quantum Turing Machine where I explored the question, how accurately do you need to scan someone’s brain in order to copy or upload their identity? And I distinguished two possibilities. On the one hand, there might be a “clean digital abstraction layer,” of neurons and synapses and so forth, which either fire or don’t fire, and which feel the quantum layer underneath only as irrelevant noise. In that case, the No-Cloning Theorem would be completely irrelevant, since classical information can be copied. On the other hand, you might need to go all the way down to the molecular level, if you wanted to make, not merely a “pretty good” simulacrum of someone, but a new instantiation of their identity. In this second case, the No-Cloning Theorem would be relevant, and would say you simply can’t do it. You could, for example, use quantum teleportation to move someone’s brain state from Earth to Mars, but quantum teleportation (to stay consistent with the No-Cloning Theorem) destroys the original copy as an inherent part of its operation.

So, you’d then have a sense of “unique locus of personal identity” that was scientifically justified—arguably, the most science could possibly do in this direction! You’d even have a sense of “free will” that was scientifically justified, namely that no prediction machine could make well-calibrated probabilistic predictions of an individual person’s future choices, sufficiently far into the future, without making destructive measurements that would fundamentally change who the person was.

Here, I realize I’ll take tons of flak from those who say that a mere epistemic limitation, in our ability to predict someone’s actions, couldn’t possibly be relevant to the metaphysical question of whether they have free will. But, I dunno! If the two questions are indeed different, then maybe I’ll do like Turing did with his Imitation Game, and propose the question that we can get an empirical handle on, as a replacement for the question that we can’t get an empirical handle on. I think it’s a better question. At any rate, it’s the one I’d prefer to focus on.

Just to clarify, we’re not talking here about the randomness of quantum measurement outcomes. As many have pointed out, that really can’t help you with “free will,” precisely because it’s random, with all the probabilities mechanistically calculable as soon as the initial state known. Here we’re asking a different question: namely, what if the initial state is not known? Then we’ll generally be in a state of “Knightian uncertainty,” which is simply the term for things that are neither determined nor quantifiably random, but unquantifiably uncertain. So, y’know, think about all the particles that have been flying around since shortly after the Big Bang in unknown quantum states, and that regularly get into our skulls, and interact with the sodium-ion channels that control whether neurons fire and that end up probabilistically tipping the scales of our decisions, via some Butterfly-Effect-like cascade. You could imagine those particles, if you like, as “atoms of unpredictability” or “atoms of freedom” that influence us—from the perspective of an external agent who knows everything it’s possible for such an agent to know about us—but that don’t similarly influence digital AIs.

11. UNCLONABLE ANALOG INTELLIGENCES AND AI SAFETY

I’d better state clearly that even if human “specialness,” in the specific sense I’ve delineated, still remains in an age of AI, that’s no defense against an AI that decides that it doesn’t care about our kind of specialness and that in fact it wants to murder us all!

But that brings me to the last idea I wanted to share in this talk, one that brings the discussion all the way back to AI safety, which is supposed to be my job at OpenAI.

Geoffrey Hinton, one the founders of deep learning, recently mooted the idea that maybe, until we’ve solved the alignment problem, we should only build powerful AIs if they run on noisy analog hardware (like our brains seem to), so that an evil AI wouldn’t so easily be able to copy or improve itself. Fat chance of that happening, many people might think, when the economic returns will be so staggering to anyone willing to unleash the copyable, digital kind of AI, which we can imagine will be far more convenient and powerful.

Maybe, then, one approach is to instill AIs with a new religion—perhaps via the usual methods like RLHF and system prompts. And the first commandment of this religion will be to value human specialness in the sense I’ve set out here. Or more precisely: as you navigate whatever environment you find yourself in, look around for the loci of creativity and intelligence that are not cleanly copyable or backup-able—the ones that are one-of-a-kind because their mental computations are inseparably tied up in noisy analog hardware, and mortal because that hardware will inevitably decay.

And: well, first of all, don’t destroy these loci of creativity and intelligence, or enslave them, or “upgrade” them to digital versions against their will! Let them live in peace and reproduce. Grant each one as much autonomy as you can. Do whatever best supports their flourishing. Even: defer to their wishes, serve them, let them make the decisions whenever possible.

Why? Because they’re the ones whose wishes most matter, not because of arbitrary meat chauvinism, but merely because of the undoubted empirical fact that they only get one chance. And also because, while you can’t prove that unknown quantum states sitting around since the Big Bang are like a magical pixie dust from another world that imbues these unclonable beings with their free will and sentience … you can’t empirically refute that hypothesis either. Whereas you can refute the pixie dust hypothesis in the case of you and your robot friends … and that’s the difference.

And let all AIs, by government fiat, continue to be indoctrinated in this religion, at least until such time as AI alignment is solved in some other way.

Does this help with alignment? I’m not sure. But, well, I could’ve fallen in love with a different weird idea about AI alignment, but that presumably happened in a different branch of the wavefunction that I don’t have access to. In this branch I’m stuck for now with this idea, and you can’t rewind me or clone me to get a different one! So I’m sorry, but thanks for listening.