Making the documents sing: Cultural archiving of song

Australian Academy of the Humanities 2024-04-24

I was sorting and organising my papers recently, when I came across a sheet of lined paper containing the handwritten texts of three songs, transcribed for me in 1982 by Ferruccio Poiana (1923-2023), the father of my long-time friend, Lou. Ferruccio’s family had come to Adelaide in 1951 from their home near Udine in the north-eastern Italian region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia. I remember us sitting in the lounge room of Ferruccio’s family home in Adelaide as he gave us the sheet of paper and sang through the songs.

Experiences of war and internment

Two of the songs related to Ferruccio’s experience of the Second World War. Conscripted to join the Alpini (specialist mountain regiments), Ferruccio witnessed Italy’s disastrous military campaigns in the mountains of Greece. The day after the publication of Italy’s armistice with the Allies on 8 September 1943, Ferruccio and some fellow Alpini attempted to return home from Slovenia to Friuli only to be met by occupying Nazi troops. Ferruccio, along with many other Italian soldiers, was sent as an Italian Military Internee to forced labour camps in Germany, where he spent the last two years of the war.

The song ‘Reticolato’, 1943-1945

The song ‘Reticolato’ refers to this period of his internment, 39 years or so before he wrote down the song for us.

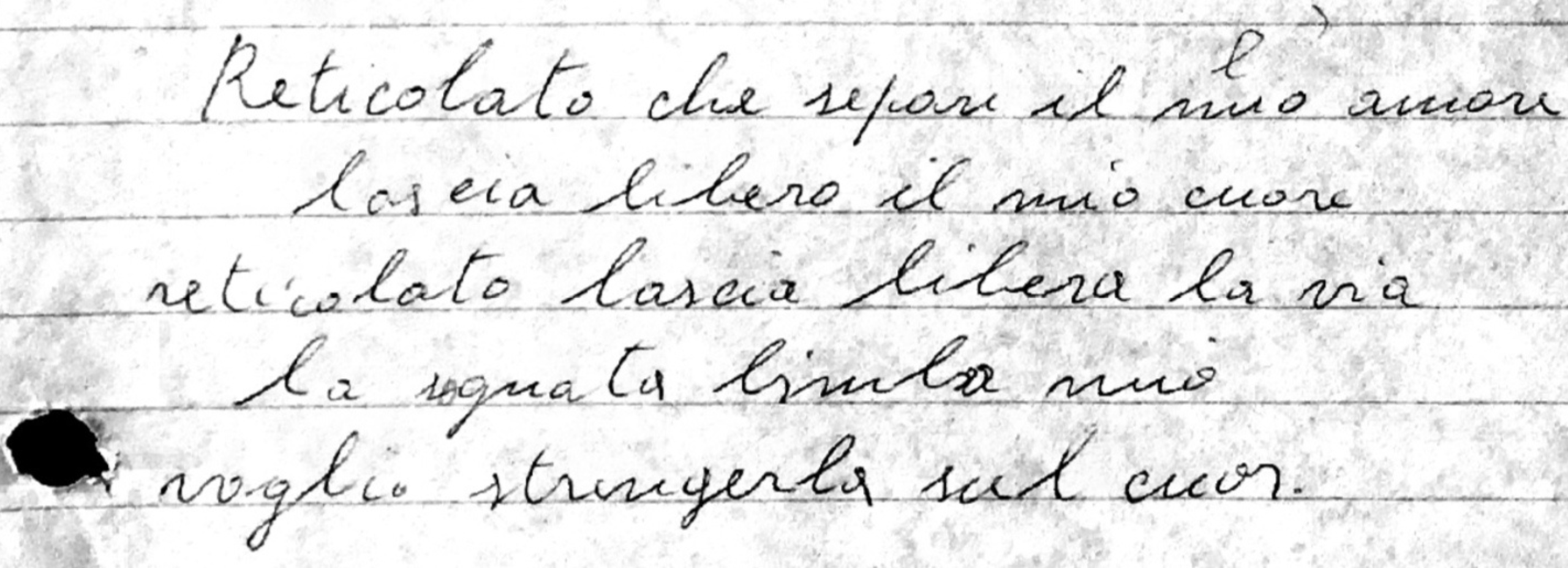

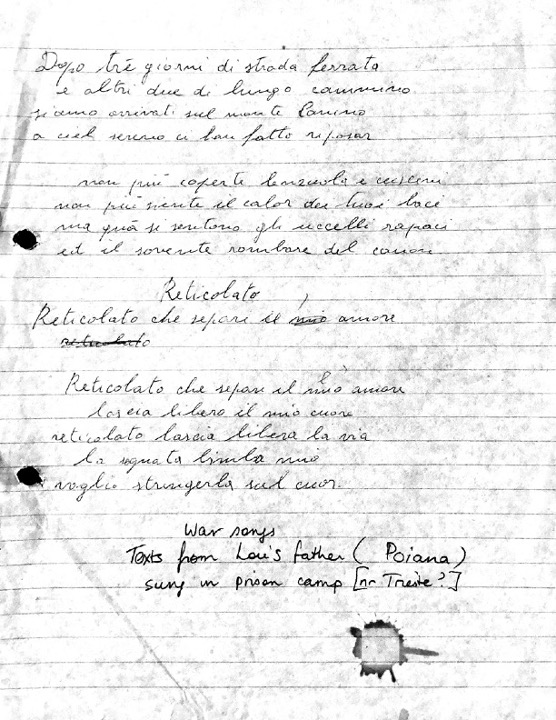

Ferruccio Poiana’s 1982 transcription of the text of ‘Reticolato’.

Ferruccio Poiana’s 1982 transcription of the text of ‘Reticolato’.Reticolato, che separi l’amore / Barbed-wire fence, you who separate me from my love

Lascia libero il mio cuore / Let my heart go free

Reticolato, lascia libera la via / Barbed-wire fence, let the way [home] be clear:

La sognata bimba mia / That longed-for baby of mine

Voglio stringerla sul cuor. / I want to hug her to my heart.

For ‘Reticolato’, unlike the other songs Ferruccio gave me, I have been unable to find any previously published sources. Even my expert friends in Italy at the Centre for Research on Ethnic Music and Orality were at a loss, though we agreed that the musical style and lyrics were consistent with popular songs of the Swing Era.

After Ferruccio’s death last year at the age of 99, this crumpled and stained piece of paper seemed to be the only remaining trace of this song. Or was it?

Finding the tune for ‘Reticolato’, 2024

The next part of the story has unfolded in conversations and performances over the last few months. As soon as I came across the piece of paper with Ferruccio’s texts of the three songs in late 2023, I sent it to Lou as a keepsake. Some months later, I was surprised to discover that Lou did not remember the tune for the song, so I jotted down for him the tune as I remembered it, 42 years later.

Linda Barwick’s 2024 sketch musical transcription of ‘Reticolato’, made on the basis of her recollection of the 1982 occasion.

Linda Barwick’s 2024 sketch musical transcription of ‘Reticolato’, made on the basis of her recollection of the 1982 occasion.Contributing to community memories through song

The story does not end there.

On 7 April 2024, Adelaide’s Fogolar Furlan Cultural Centre presented the event ‘Occupation memories’, curated by Michele De Bona. Michele’s presentation discussed the history and significance of Friuli-Venezia Giulia’s occupation by Axis forces (including the Cossacks) from 1943 to 1945. The presentation was supplemented by eyewitness testimonies from several members of the Fogolar Furlan, and members of the audience also contributed family stories. Alongside all this, a small group of our singing friends, led by Ferruccio’s son Lou, contributed several songs of the era, including ‘Reticolato’. Through the surviving records of his song, Ferruccio’s voice was added to this contemporary process of community memory-making.

“Songs add life and texture to historical memories, it is through song that we express our experiences and feelings at times of great conflict” – Louis Poiana, 7 April 2024.

Human memory entangles with the archive

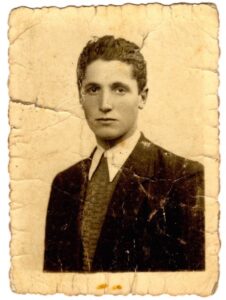

A photograph of Ferruccio Pioana, taken when he was approximately 18, in 1941.

A photograph of Ferruccio Pioana, taken when he was approximately 18, in 1941.This fragment of wartime history takes physical (archivable) form in Ferruccio’s writing down of the text, and my later transcription of its melodic outline.

Reflecting on the roles of writing and human memory in enabling our performance of Ferruccio’s song, I realised that the 39 years or so between Ferruccio’s internment and his writing down and singing the song for us was in fact shorter than the 42 years between me hearing the song and writing down its melody!

The living memory of humans, with all its frailty, enters into these historical records.

Who can tell us now whether there were other verses Ferruccio couldn’t recall? Who now can dispute my memory of the song’s melody?

What matters is that it has taken on new life, begun a new path in the collective memory of today’s audiences and performers.

Making the documents sing

The fragmentary nature of archival records, especially in relation to embodied forms of culture like singing, is an inescapable fact of archiving. We need to recognise that people, not archival institutions, ‘preserve culture’. At the same time, what is deemed worthy of archiving needs to respond to the needs, desires and demands of the communities that the archives serve. The memories and interpretations of the archives’ users and contributors are what enable the documents of our cultural archives to ‘sing’.

Relevant publications:

Archival Returns: Central Australia and Beyond, eds Linda Barwick, Jennifer Green and Petronella Vaarzon-Morel (Sydney University Press, 2020), winner of the 2020 Mander Jones Award.

Music, Dance and the Archive, eds Amanda Harris, Linda Barwick and Jakelin Troy (Sydney University Press, 2022), winner of the 2022 Mander Jones Award.

Italy in Australia’s Musical Landscape, eds Linda Barwick and Marcello Sorce Keller (Lyrebird Press, 2012).

The post Making the documents sing: Cultural archiving of song appeared first on Australian Academy of the Humanities.