slip(per)

Language Log 2014-07-22

Jonathan Dushoff sent in this photograph of a sign in the Lukang (Lùgǎng 鹿港) public library in Taiwan (apologies for the reflection off the surface):

Jonathan says, "It's obvious how a computer would make that translation; not clear why a human (at the library!) didn't spot it."

The translation software (or somebody) made this mistranslation ("Invites the slipper") because of problems with polysemy, parsing, and homophony. As a matter of fact, depending upon their frame of mind and level of familiarity with Chinese language and characters, even a human being may have to pause for a moment to correctly interpret the intended message.

The Chinese consists of three characters, each with bopomofo phonetic annotation along the right side):

qǐng 請 ("please; invite; request") tuō 脫 ("take off; remove; shed; doff; escape; get away; come off") xié 鞋 ("shoe")

Google Translate, Baidu Fanyi, and Bing Translator all render it perfectly as "Please take off your shoes." Even iCIBA has "shoes off; please take off your shoes; take off your shoes; please take your shoes".

One begins to wonder how this mistake ("Invites the slipper") actually occurred. Where did the "slipper" in the sign come from, if not from translation software (which doesn't seem to be the culprit in this case)?

The Mandarin word for "slipper" is tuōxié 拖鞋, which consists of two morphosyllables:

tuō 拖 ("drag; haul; tow; pull; draw; delay") xié 鞋 ("shoe")

Thus, it would appear that the homophonous term tuōxié 拖 鞋 ("slipper") interfered with the processing of tuō xié 脫鞋 ("take off / remove shoes") and replaced it in the English translation.

I asked about two dozen native speakers of Mandarin if they thought that they pronounced tuōxié 拖鞋 ("slipper") and tuō xié 脫鞋 ("take off / remove shoes") exactly the same. The results of my survey are rather astonishing.

Nearly all individuals who are highly literate in characters (humanists) and professional language teachers maintained that they pronounced tuōxié 拖鞋 ("slipper") and tuō xié 脫鞋 ("take off / remove shoes") in an identical fashion. But there were two categories of native speakers who perceived a difference in their own pronunciation of the two expressions: those who are highly qualified linguists and those who are not very literate in characters. How can we make sense of this phenomenon?

I think that, when native speakers claim they are pronouncing these two expressions in exactly the same way, they are being unduly influenced by the characters, that they are indulging in what we may refer to as "reading pronunciation". It's somewhat comparable to someone pronouncing "Wednesday" and "February" the way they are spelled instead of the way they are spoken in real life.

As for myself (although I am not a native speaker, I possess near native fluency in MSM), I have never felt that tuōxié 拖 鞋 ("slipper") and tuō xié 脫鞋 ("take off / remove shoes") were pronounced identically in actual speech. Simply for innate, cognitive reasons, I'm certain that I make a slight pause between 脫 and 鞋 of 脫鞋 ("remove shoes"; VO), whereas there is no pause between the two syllables of the disyllabic noun 拖鞋 ("slipper") in actual speech. For example, in these two sentences:

chuān tuōxié 穿拖鞋 ("wear slippers") qǐng tuō xié 請脫鞋 ("please take off [your] shoes")

I will definitely insert a slight pause between the 脫 and 鞋 of 脫鞋 ("remove shoes"), but not between the two syllables of the noun 拖鞋 ("slippers").

When I asked my semi-literate or illiterate (in characters) friends who are native speakers of Mandarin why they thought tuōxié 拖鞋 and tuō xié 脫鞋 were not identical in pronunciation, most of them could not articulate any particular reason, but when I pressed them further, several of them said that it was due to the fact that tuō xié is a verb-object construction, whereas tuōxié is a noun. Incidentally, I elicited their responses simply by wearing a pair of slippers and by taking off one of my shoes, and asking them to say what I was doing in each case, then asking them to tell me if they thought the word for "slipper" and the words for "take off" sounded exactly alike.

Now, when it comes to the linguists, we get much more sophisticated explanations, such as this one from Jiahong Yuan:

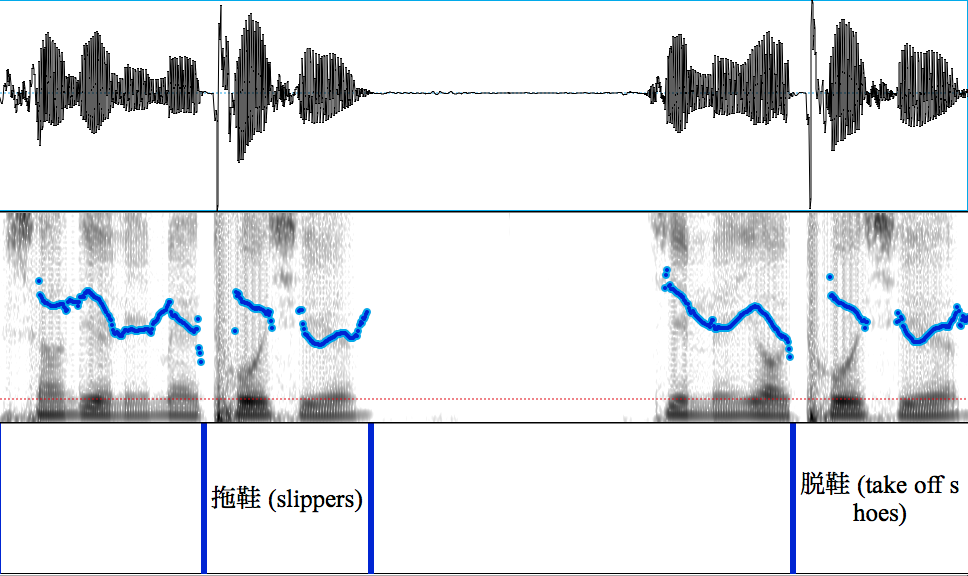

Attached is a recording I made. It contains two sentences: shāngdiàn lǐ mài tuōxié 商店里卖拖鞋 ("in stores that are selling slippers"), and jìnmén yào tuō xié 进门要脱鞋 ("when you go inside you have to take off your shoes"). The words "tuoxie" are marked in the textgrid file. 拖鞋 and 脫鞋 are probably slightly different in my pronunciation, but the intuition is vague.

San Duanmu's proposal is that in Mandarin Chinese disyllabic words have a stress on the first syllable; compounds have a stress on the non-head word. So in 拖鞋 (a disyllabic word) the first syllable should be stronger, and in 脫鞋 (VO compound) the second syllable should be stronger (The phonology of Standard Chinese: pp.136). And the relationship between 鞋 and 拖鞋 is related to what San calls "elastic word length": see his papers 现代汉语词长弹性的量化研究 [A quantitative study of elastic word length in Modern Chinese] and "How many Chinese words have elastic length?".

Catherine, Yanyan and I did a study on the stress patterns of polysyllabic words in Mandarin, and we found that the first syllable of a disyllabic word is stronger: Catherine Lai, Yanyan Sui & Jiahong Yuan, "A Corpus Study of the Prosody of Polysyllabic Words in Mandarin Chinese", Speech Prosody 2010.

BTW, the drawing on the sign seems to suggest that patrons are encouraged to go barefoot in the library, which would be frowned upon in most American libraries. On the other hand, I don't know how one might visually indicate that patrons are requested to enter the library in stocking feet.

[Thanks to Zhao Lu, Maiheng Dietrich, Grace Wu, Melvin Lee, Liwei Jiao, Rebecca Fu, Wei Shao, Ziwei He, Jiajia Wang, Andy Lee, and several informants who wish to remain anonymous]