Squeezing more information out of the cosmic microwave background

Ars Technica » Scientific Method 2013-03-02

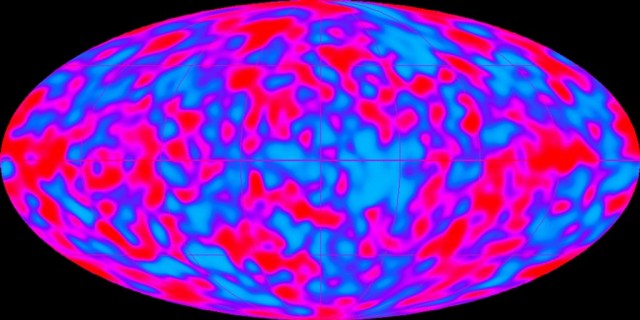

The cosmic microwave background was created 300,000 years after the Big Bang, when the Universe cooled enough to allow electrons to link up with protons and form hydrogen atoms. The short gap between the two events means that the CMB captures details of the birth of our Universe, like its composition and the processes leading to its current state. So far, Nobel Prizes have been awarded both to its discovery and to the first detailed characterization of its properties.

But we're not through with it yet. At the recent meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, researchers talked about how telescopes in out-of-the-way places (including one at the South Pole) are using the CMB as a spotlight to identify some of the largest galaxy clusters ever seen. And they gave a big tease about upcoming results from the European Space Agency's Planck mission, which may finally settle key questions about the Hubble constant and the types of neutrinos present in the Universe.

A bit of history

John Mather, one of the Nobel-winners for his work on the COBE mission, provided an introduction to the CMB and the Big Bang that created it. The formation of hydrogen atoms was a Universe-wide phenomenon, so the CMB pervades its structure—anywhere you go in space, you will be bathed in it. As Mather put it, the CMB and the Big Bang are inseparable from the fabric of the Universe itself: "If anybody says 'here's a picture of it, and this is where it happened,' I'm choking them."

Read 11 remaining paragraphs | Comments