2002 Larsen B ice shelf collapse likely due to rising temps

Ars Technica » Scientific Method 2014-09-12

A number of noteworthy studies have recently highlighted the importance of what's going on at the bottom of glaciers that flow into the ocean. The topography beneath the glacier—as well as the “grounding line” beyond which a glacier becomes thin enough to float in the water rather than rest on the seafloor—have a lot to do with its stability.

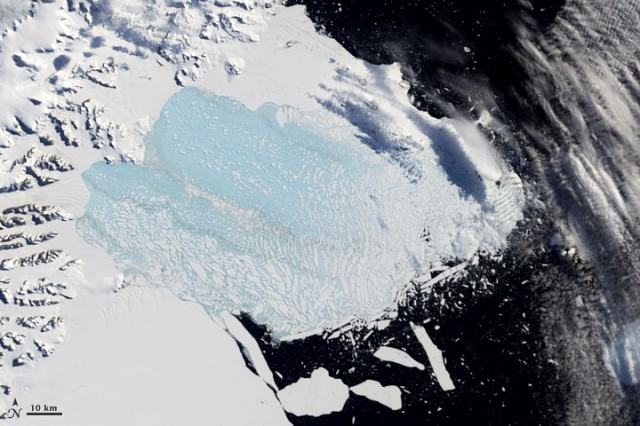

In 2002, the Larsen B ice shelf on the Antarctic Peninsula abruptly collapsed, scattering 3,200 square kilometers (yes, approximately one standard Rhode Island unit of area) of 200 meter thick ice into the waves. But why? Did warming water beneath the ice shelf loosen it from the grounding line and destabilize the ice shelf in front? Or can we pin the blame on the warming temperatures of the region?

With the ice shelf gone, researchers looking for answers have been able to look at the seafloor that once sat beneath it. In 2006, a research vessel spent some time at the site of the collapse, looking for clues. The findings of that team, led by the Italian National Institute of Oceanography and Experimental Geophysics’ Michele Rebesco and the University of South Florida’s Eugene Domack, have now been published in the journal Science.

Read 6 remaining paragraphs | Comments