The Milky Way’s black hole, like Cookie Monster, loses more than it eats

Ars Technica » Scientific Method 2013-08-29

Despite the common conception that they suck down everything that passes nearby, black holes are messy eaters. Gas swirls around them due to the strong gravitational field, but much of the material is blasted back into the surrounding galaxy. In many galaxies, that messiness makes the black hole extremely bright, but the Milky Way's supermassive black hole devours material so inefficiently that it's actually one of the quieter galactic nuclei around.

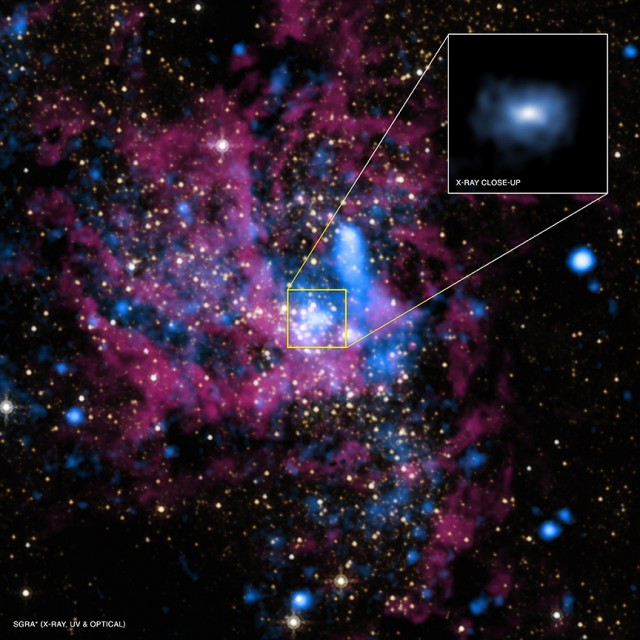

A high-resolution measurement of X-ray emissions near the galactic center shows the structure and feeding of the Milky Way's monster in new detail. Q. D. Wang and colleagues determined the light it does produce comes from a very compact region right near the galactic center. That supports the hypothesis that X-ray emissions are due to black hole accretion—mass falling into orbit around it. They also determined that no more than one percent of all the accreted matter ever crosses the black hole's event horizon.

The existence of the Milky Way's black hole is uncontroversial. The motion of nearby stars and the behavior of the local gas reveal the presence of a compact, massive object. Its mass is roughly four million times that of the Sun and its radius is smaller than the Solar System, which rules out nearly every alternative explanation.

Read 6 remaining paragraphs | Comments