Gravitational waves show deficit in black hole collisions

Ars Technica » Scientific Method 2013-10-17

How do supermassive black holes grow to be millions or billions of times bigger than their more ordinary cousins? No star grows that huge, so they aren't created from the same kinds of supernovae that make stellar-mass black holes. The earliest known galaxies indicate that these monsters were present from nearly the start, meaning that they were unlikely to be normal black holes that slowly gorged their way to supermassiveness. One potential explanation that has been considered is that they were born large and became truly gigantic when two or more collided and merged.

New observations could place stringent limits on that merger rate, however. R. M. Shannon and colleagues used the timing of light from pulsars as a means of measuring gravitational radiation. Gravity waves should be generated by pairs of black holes before and during their collisions. If there were a lot of mergers, the waves would create a noticeable fluctuation in the pulsar timing. But the new results are inconsistent with the merger rate predicted by the most widely accepted theoretical models, suggesting that either binary black holes don't collide as often as expected or that some other mechanisms for their growth are at work.

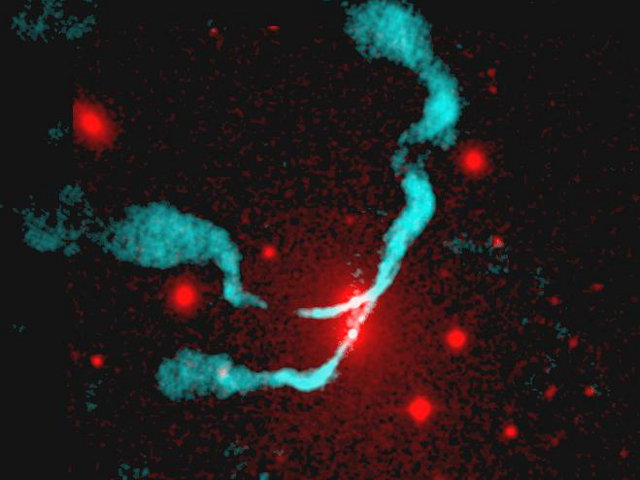

Supermassive black holes (SMBHs), which are hundreds of thousands to billions of times more massive than the Sun, lie at the center of nearly every large galaxy. These objects frequently drive powerful jets of matter, which (if the alignment is right) astronomers observe as quasars. The most distant quasars indicate that SMBHs have existed nearly as long as galaxies. Their large mass and early existence indicate that they could not have formed from the explosions of large stars, which is the mechanism by which stellar-mass black holes are born.

Read 9 remaining paragraphs | Comments