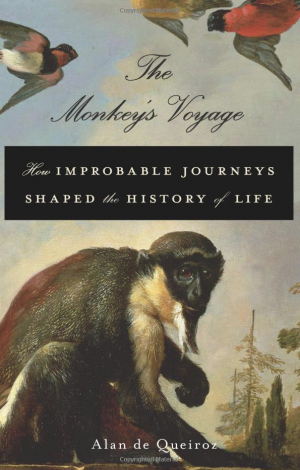

How the vastly improbable has determined what animals got where

Ars Technica » Scientific Method 2014-02-08

The new book The Monkey's Voyage asks a deceptively simple question: how did we get here? My grandparents took a boat to New York in 1948 after spending three years in a displaced persons camp in Germany after the Nazis had just murdered most of their families. But how did kiwis—flightless birds—get to New Zealand? And how did frogs—whose skin will quickly desiccate if exposed to either air or salt water—get to volcanic islands like Príncipe and São Tomé, off the east coast of Africa?

Taxonomic groups like species can get split into two or more populations by the development of a "barrier to dispersal;" in biogeography, this is called vicariance. These barriers can be formed by the shifting tectonic plates that move continents, widen oceans, and create mountain ranges, or they can be formed by climate changes that submerge or create land bridges or form vast, impassable deserts.

But geology doesn't only separate. All of the continental land masses used to be connected in one primordial supercontinent called Gondwana (you must admit, it sounds more scholarly than Pangaea). So southern beech trees—with seeds that cannot survive in seawater—are found on Australia and New Zealand, while crocodiles are found in South America. When Gondwana began to break apart about 160 million years ago, the different pieces acted like rafts for these species, keeping them—or their ancestors—afloat.

Read 10 remaining paragraphs | Comments