The oldest piece of the Earth, examined atom-by-atom

Ars Technica » Scientific Method 2014-02-24

Human artifacts are particularly good at capturing our imagination. Whether looking at a stone axe or feeling the walls of an old castle, we’re prone to wishing these inanimate objects could tell us about the things they’ve “seen.” But there's something mind-expandingly thrilling about holding something truly ancient. I’ve seen the eyes of even the most too-cool-for-this student widen when shown a three-and-a-half billion year old rock. Fascinating scientific questions aside, any ancient pieces of the Earth ever found are just plain cool.

Recently, researchers have taken a new and more careful look at the very oldest minerals we've found on Earth. The results lay to rest worries that internal variations created a mistaken date for the mineral's formation, hinting that the Earth hasn't been completely molten since the immediate aftermath of the collision that formed the moon.

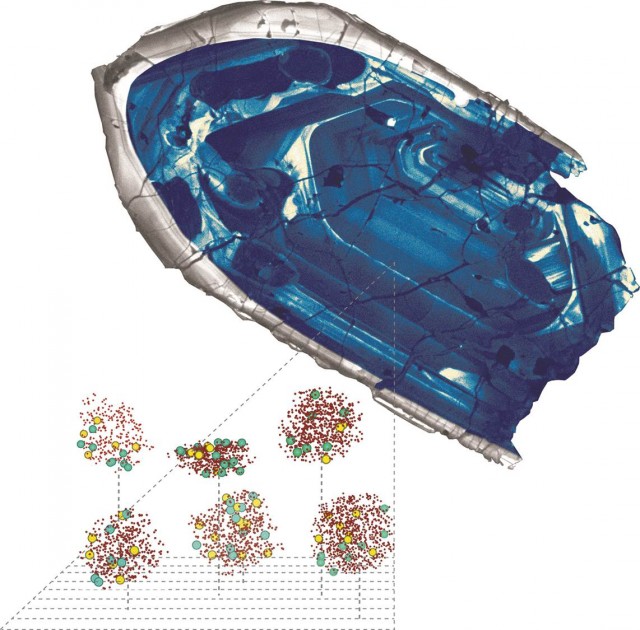

If you didn’t know their age, you might not see their appeal. In fact, you might not see them at all. These miniscule crystals of zircon—a mineral beloved by geologists because of its extraordinary resistance to the march of time and the interesting things that can be found inside it—are less than a half millimeter in diameter. The latticework of zirconium, silicon, and oxygen atoms that make up zircon also form cages that imprison foreign elements that get trapped inside. Those elements include radioactive uranium and the lead it decays into—grains of sand in an hourglass that allows geochemists to calculate the age of the zircon and, by association, the igneous rocks within which they formed.

Read 12 remaining paragraphs | Comments