New find hits Cambrian fossil jackpot—again

Ars Technica » Scientific Method 2014-02-24

The odds of any individual organism making it into the fossil record are, frankly, terrible. Leaving aside the fact that some animal may eat you and scatter your remains, there’s the menace of rot to contend with, as the same oxygen that keeps animals alive also fuels the bacteria that decompose organic matter. Your best bet, if you want to be immortalized in the rock record and puzzled over by future beings, is to be buried—and quickly—in a low-oxygen environment.

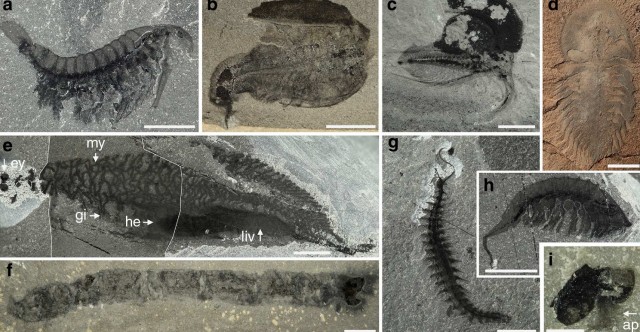

The rare crown jewels of the fossil record are rocks that were deposited in conditions so ideal that details of soft tissue structures can be seen. These exquisite bonanzas are obviously terribly interesting and useful to paleontologists, whether they hold feathered dinosaurs or some of the earliest animals in evolutionary history.

In 1909, Charles Doolittle Walcott stumbled on an incredible outcrop of shale in the Canadian Rockies that pulled back the curtain on some of the organisms produced by the Cambrian explosion of life. This group of organisms, dubbed the Burgess Shale biota, included the iconic trilobite as well as the downright weird (and aptly named) Anomalocaris and Hallucigenia. In 1984, similar but slightly older rocks in China began yielding the Chengjiang biota, increasing the wealth of Cambrian organisms known to science.

Read 6 remaining paragraphs | Comments