Dust in the wind helped bring down CO2 in the past

Ars Technica » Scientific Method 2014-03-21

Over the past three million years, the Earth has experienced rhythmic swings in and out of glacial conditions paced by a drummer named Milankovitch. The Milankovitch cycles in Earth’s orbit around the sun change the way the sun’s light strikes the surface of our planet. But these climatic swings would have been much smaller if not for the amplifying effect of changing greenhouse gas concentrations. (Returning to a band metaphor, a rock concert would be pretty unremarkable if you disconnected the amps from the guitars.)

Climate records like ice cores very neatly show us how those concentrations changed over time, since they hold bubbles of ancient air trapped in the ice. But it’s up to us to figure out why greenhouse gasses moved in to and out of the atmosphere. For example, where did all the atmospheric CO2 go when the warm interglacials descended back into glacial conditions?

Hiding carbon in the ocean

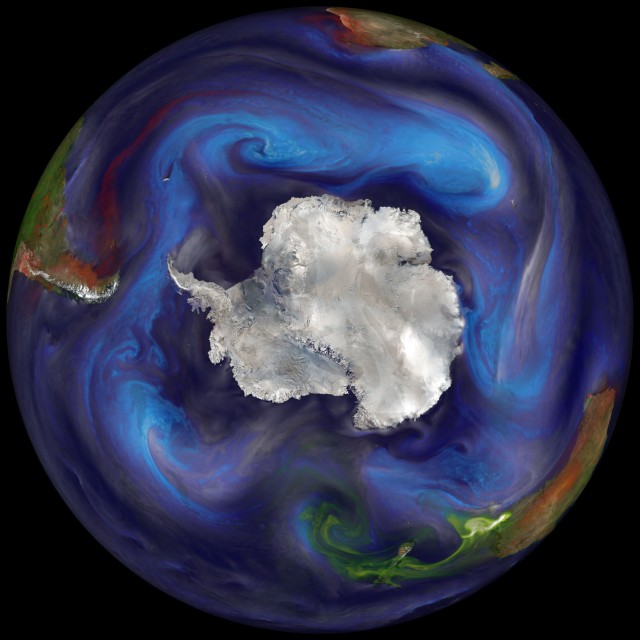

The Southern Ocean has been the prime suspect. There, CO2-rich deep ocean water rises to the surface and exchanges gas with the atmosphere. If that ventilation were too slow, atmospheric CO2 would fall. Reduced upwelling caused by a lid of lower-density water near the Antarctic coast, for example, could explain up to 40 parts per million of the approximately 100 parts per million decrease in CO2 over the recent glaciations.

Read 12 remaining paragraphs | Comments