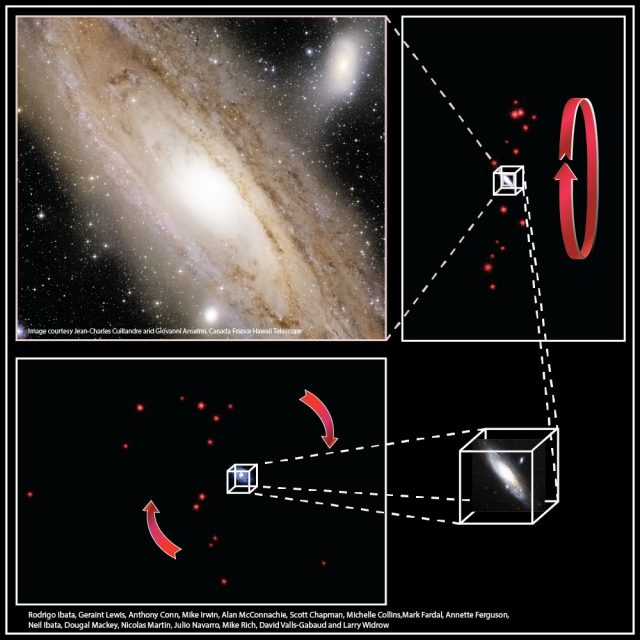

Half of Andromeda's satellite galaxies orbit in a mysterious disk

Ars Technica » Scientific Method 2013-01-03

Large galaxies such as the Milky Way have many smaller satellite galaxies, bound to them by gravitation. According to the widely accepted theories of galaxy formation, these satellites were leftovers from the slow merger process that made the larger galaxies. We'd expected these satellite galaxies to be evenly distributed around the Milky way, but recent studies showed that many of them lie close to a single plane, tilted with respect to the Milky Way's disk. New observations may have revealed a similar structure of satellites around our closest large neighbor M31, also known as the Andromeda Galaxy.

Rodrigo A. Ibata and colleagues found that nearly half of M31's known satellites lie in a single, relatively thin plane. They also measured the motion of these galaxies and found they were revolving in the same direction around Andromeda. These results—as with the previous Milky Way observations—were contrary to expectations, in which satellites would be distributed more or less spherically and moving in random directions.

A complete census of Milky Way satellites is difficult to achieve. Since we are located within the Milky Way's disk, a large part of the sky is obscured by our own galaxy, which may block the view of several small galaxies. While a few examples of the satellite galaxies are large—the Magellanic Clouds for the Milky Way and the Triangulum Galaxy (M33) for Andromeda—most are small and faint, increasing the challenge of locating them all.

Read 7 remaining paragraphs | Comments