Strange animals may have their own distinct nervous system

Ars Technica » Scientific Method 2014-05-23

What did the first animals look like? If you looked around at today's world, you probably guess something like a mammal or an insect: something with left-right symmetry and a centralized nervous system. But look a little further, and you get things like jellyfish, which are radially symmetric and have a decentralized nerve net. Look further still, and you get bizarre things like the Trichoplax, which don't have any visible nerve or muscle cells yet sense light and coordinate their movements. And then there are sponges, which clearly don't have anything nerve- or muscle-like, but these animals have many of the genes required to form key structures in the nervous system.

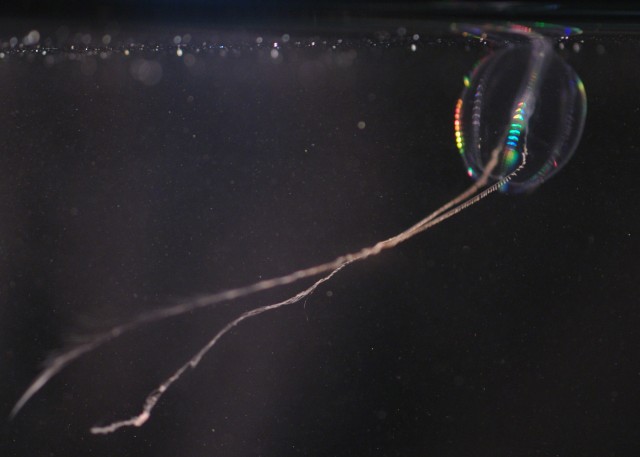

If you think this suggests that early animals started out simple and gradually evolved new features, and things like sponges branched off before they were added, you wouldn't be alone. Over the years, lots of researchers argued the same thing. But a recent genome sequence indicated that the oldest branch of the animal family tree that led to the comb jellies, with muscles, nerves, and tentacles, were an older branch than sponges. Now with a new paper on the comb jelly, researchers are starting to argue over what this actually tells us about the earliest animals.

The arguments started with the publication of the first comb jelly genome, which helped establish them as the earliest branch. The authors of that paper suggested that this indicated that the earliest animals came fully equipped with muscles and nerves, which implies sponges lost both of these structures. In this view, the genes sponges possess that are similar to those used in nerves aren't hints of the assembly of a nervous system; instead they're remnants of structures that are no longer made.

Read 8 remaining paragraphs | Comments