Beyond Gravity: the complex quest to take out our orbital trash

Ars Technica » Scientific Method 2014-05-27

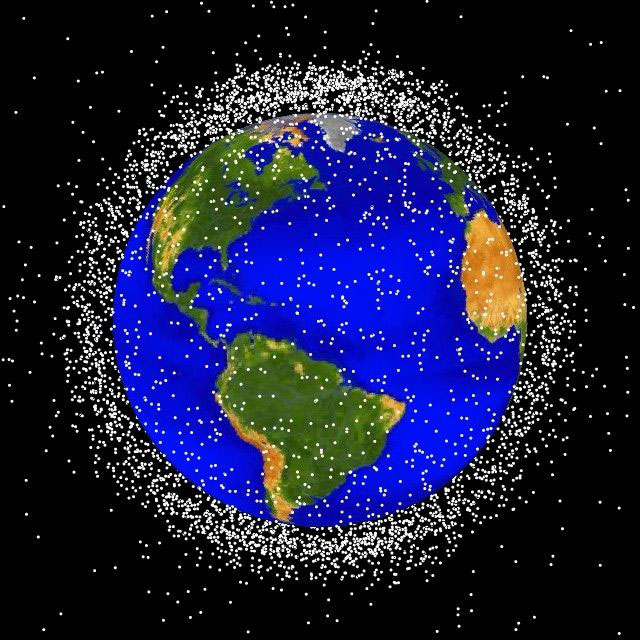

As Gravity made clear to the general public, it’s getting crowded in Earth orbit. In the nearly 57 years since Sputnik’s launch on October 4, 1957, Earth has seen a cloud of human-created objects continue to grow, expanding like dandelion fluff around our planet. In 2014, there’s good and bad news on the subject.

Some good news is that Gravity’s makers seized on a plausible scientific disaster scenario—the Kessler syndrome, an expanding cascade of space debris—and amped the volume up to 11 for dramatic purposes. The filmmakers kept only as much science as they felt like keeping, as movie-makers have done before. (The China Syndrome did it with nuclear meltdowns in 1979, for instance.) The actual science detailing how a Kessler-type situation would unfold presents a more nuanced picture than Gravity.

The bad news is that the Kessler syndrome isn't merely some science-fictional theory hyped by Gravity. In a true case of Kessler syndrome, the density of orbital objects becomes so great that collisional cascading is triggered, and one initial collision generates ever more smash-ups among ever greater quantities of space junk. We’ve already reached the point where the growth of debris in low Earth orbit (LEO) has become self-sustaining. Human access to space might eventually become impossible.

Read 53 remaining paragraphs | Comments